New York City’s Renewed Vibrancy Is Hiding Deep Economic Pain

An economic pain persists in a city where twice as many people are unemployed compared to the seasonally adjusted U.S. average.

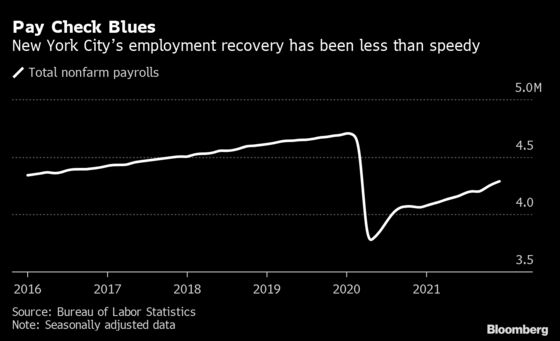

(Bloomberg) -- New York City’s apartment sales are sizzling, popular restaurants are booking up and Covid mandates are fading away. But underneath the buzz, an economic pain persists in a city where twice as many people are unemployed compared to the seasonally adjusted U.S. average.

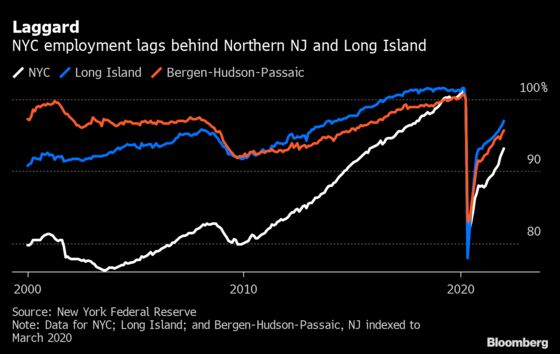

At 7.6%, the city’s unemployment was among the worst of major cities. It also lags behind neighboring Northern New Jersey and Long Island. The jobless rate jumps to 11.1%, not seasonally adjusted, in the Bronx, the highest of New York’s five boroughs, and even higher for Black New Yorkers, who were disproportionately impacted by job losses during the pandemic.

“New York’s economy is enduring a slower recovery because it is so dependent on the office and entertainment sectors,” said Mark Vitner, a Wells Fargo senior economist. “Cities that were quicker to reopen following the initial lockdowns at the start of the pandemic have also tended to see stronger recoveries.”

Two years after Covid drove the economy into a spiraling downturn, jobs across the U.S. have roared back. Prices are climbing at their highest pace in decades. The labor market is so strong that millions of workers are leaving their jobs in what’s been nicknamed the Great Resignation.

Not so in New York. Bank earnings and real estate prices have soared but offices in Midtown Manhattan and the Financial District remain under-occupied as employees opt to work from home. Subway ridership remains at just 60% of pre-pandemic levels.

Surrounding businesses, especially in the service, hospitality and entertainment industry, have been slow to recover from the worst of Covid. The tourism industry, which accounts for 7% of private-sector employment, hasn’t lured back the international travelers. The result is that some jobs don’t appear to be returning just yet. For some, it’s prompting a rethinking of how to breathe new life into the city's economy.

But for now, businesses remain on edge as workers ebb and flow with Covid rates, said Erkan Emre, founder of Kotti Berliner Döner Kebab, which has four restaurants in the city.

He’s particularly concerned about his outpost in The Hugh, a food hall in Midtown Manhattan. Other locations got by with take-out orders. The Hugh, though, relies on office workers, who have been slow to return. Unless something changes, he said office-centric locations will “continue to suffer.”

Since becoming mayor in January, Eric Adams has been pleading for firms to bring workers back to the office. He even showed up to Goldman Sachs’s Tribeca headquarters earlier this month to cajole bankers to return, stressing their place in the ecosystem of coffee shops, retailers and dry cleaners that depend on white-collar workers.

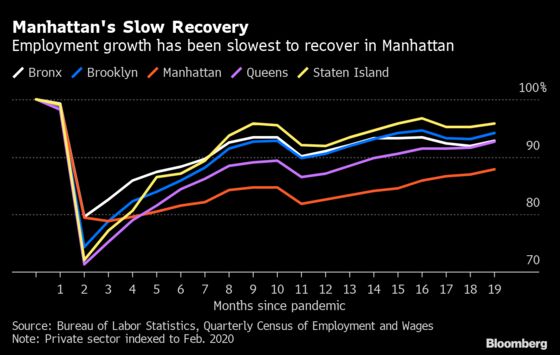

Manhattan Malaise

In Manhattan alone, about 275,000 fewer paychecks are being doled out than in March 2020, according to the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages data. Manhattan jobs account for 57% of the city’s, directing the overall economy and commanding higher wages than other boroughs.

Manhattan’s unemployment rate is lowest among the boroughs, but that may reflect the people who simply left the labor market — or the city altogether: The borough’s population dropped by 1% in 2020, according to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

“Manhattan is an enormous economic and social driver,” said Andrew Rigie, executive director of the New York City Hospitality Alliance. The Broadway shows, museums and restaurants attract visitors who go on to explore nearby boroughs.

But the pandemic made some Manhattanites rethink their locales. Rianna Eduljee, a financial analyst, said she fled the city when the pandemic hit to stay with her family in Seattle and never returned. She was done with the 80-hour workweeks on Wall Street and wanted work-life balance.

“Stepping outside of that New York, and then, banking-specific, bubble, I was just able to see ‘Oh, there’s a different way of living life,’” Eduljee said.

Despite the departures, Manhattan rental costs remain the highest in the U.S., at $4,172 according to Yardi, nearly three times the U.S. average. Tight inventory in many neighborhoods is driving prices higher: During the first 11 months of 2021, just 506 units had come online, 0.2% of existing housing stock and less than a tenth of the national rate.

Beyond the headline employment number, the city’s under-employment rate was 13.5% factoring in involuntary part-time employment and discouraged workers. That rises to 19% for Black residents, who made up a larger share of workers in the service industry and other face-to-face jobs that can’t be done remotely, according to economist James Parrott of the Center for New York City Affairs at The New School.

Black workers are also more highly concentrated in essential industries, like health care, transit and public services, where exposure to Covid and burnout have been significant factors, Parrott said.

Rebuild, Renew, Reinvent

Policy makers, analysts and business leaders say it’s time to rethink what an economic recovery might look like without as many office workers. Same goes for the city’s reliance on international tourists, as well as the hospitality, finance and real estate industries.

A survey conducted by HQ Travel, a corporate mobility provider, found that only 30% of employees are badging in to work during the week compared to 2019. The data was based on 50 clients and 70 car providers from the Tri-State area, which encompasses parts of New York and neighboring states New Jersey and Connecticut. The February survey found just a fifth of companies plan to come back fully.

“This is likely going to be a structural break in the way that people view work and commuting and just being in an office,” said Alex Heil, vice president of research for the Citizens Budget Commission.

With fewer workers and less office space, desolate buildings could be transformed.

It’s “easy to get stuck and imagine that corporate office buildings from the 1950s is what Midtown is,” said New York City Comptroller Brad Lander. “New York City has changed its footprint many times.”

Lander imagines a city where empty offices are replaced with cultural centers, biotech labs and startup incubators. Instead of “wagging our fingers at corporate businesses and lecturing them to get back to a five-day work week,” Lander said the city will adapt.

In a 63-page economic recovery plan released this month, Mayor Adams vowed to first tackle New York’s elevated violent crime rates and expand a marketing campaign to lure tourists back. He vowed to create a new fund to attract big events like the FIFA World Cup to the city, while deploying a “Culture at Risk” task force to help struggling theaters, comedy clubs and bookstores.

Adams also wants to help diversify the city’s economy by bolstering burgeoning sectors like digital gaming and recreational marijuana.

“We can’t stumble into post-Covid,” Adams said. “We must start to think about the redefinition of what our city is going to look like.”

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.