Fixing Nursing-Home Death Traps Is Key to Europe’s Virus Fight

Fixing Nursing-Home Death Traps Is Key to Europe’s Virus Fight

(Bloomberg) --

When Spain went into coronavirus lockdown in March, Veronica Munoz’s grandparents were in a nursing home north of Madrid, sharing a room just big enough for their wheelchairs. Munoz and other family members called the facility daily to check on the couple, but they weren’t alerted to any concerns until Munoz’s 97-year-old grandfather, Jesus, had been ill for a week and was too frail to talk on the phone. On April 11, as Jesus got sicker, the staff moved his wife, Basila, out of the room. On April 12, he died alone—and Basila, 96, still hasn’t been told her husband of seven decades is dead.

Jesus was never tested for the virus, but it was rampant in the home, and Basila was confirmed positive a day after his death. “Everything was so confusing, you feel helpless,” Munoz said. “They tell us she doesn’t have symptoms, but we don’t believe anything they say anymore. I’ve talked to her just once, and she asked when we might visit. I didn’t know what to say.”

Even as Europe’s leaders slowly begin to chart a course out of coronavirus lockdown, the grim extent of mortality in the region’s retirement homes is just beginning to emerge. As many as half the people killed by the coronavirus in Europe were residents in long-term care facilities, the World Health Organization said on Thursday.

The data show a “deeply troubling” picture of the vulnerability of older people in care, said Hans Kluge, regional director for WHO Europe. He said even the oldest patients have a good chance of recovery from the virus if they’re well cared for, but procedures at some facilities have helped spread the virus. “This is an unimaginable human tragedy,” Kluge said.

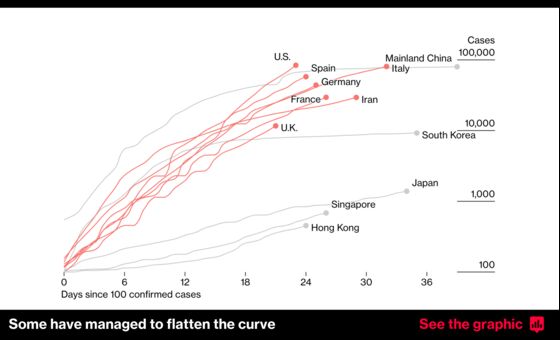

Containing the virus in care homes will be key to weathering the pandemic in the coming months in Europe and places such as the U.S. as the outbreak spreads. Almost 4 million Europeans live in nursing homes, both privately owned and state-operated, and with populations aging, their numbers jumped more than a fifth in the decade to 2017, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

As governments move to ease restrictions and get their economies moving again, they’ll need to ensure the safety of people in homes. Based on the alarming numbers, Europe's health officials are preparing a surveillance system to monitor virus deaths at facilities for the elderly—both to improve the standards of care and to alert authorities if “a second wave is coming, which we expect,” said Agoritsa Baka, a senior expert at the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Retirement homes “need to be much more alert to what is happening, both to staff and residents, to prevent this thing from happening again,” Baka said.

Accounts from workers and families show that as Europe’s nursing homes struggled to address the virus, policies on protective gear and quarantining positive cases were sometimes implemented too late to save lives. In some countries, a shortage of tests made it difficult to track the spread. And families–themselves confined at home–struggled to get basic information about their relatives’ health.

In Mougins, a village surrounded by pine and olive forests in the hills above Cannes in southern France, families remained in the dark as the virus killed more than a third of the 109 residents in La Riviera, a private facility run by Korian SA, according to Fabien Arakelian, a lawyer representing families of people at the home. One client heard about her father’s death via a text message from undertakers, he said. With visitors barred from French nursing homes until this week, none were able to see their relatives before they died.

“It’s the law of silence,” Arakelian said, adding that residents weren’t screened for the virus until April 6, several days after some caregivers had tested positive.

The prosecutor in the nearby city of Grasse has opened an investigation. Emmanuel Daoud, a lawyer working for Korian, Europe’s biggest operator of nursing homes, says staff followed regulations and exhibited no negligence in their care.

Some facilities spared thus far are struggling with a lack of tests. After a staffer was confirmed to have the virus at Les 3 Moulins, a 72-resident home in Sainte-Gemmes-sur-Loire, in western France, testing all patients and staff wasn’t an option, according to director Delphine Lecomte. So the staffer was given a three-week sick leave, “and we’re monitoring other people for symptoms,” Lecomte said.

Assessing the true toll has been a struggle across Europe. France initially didn’t count nursing-home deaths in its official virus tally, and when it started including them in early April, daily fatalities more than doubled. In Spain, an unpublished government report cited by RTVE public television on April 23 estimated that retirement-home patients accounted for two-thirds of overall coronavirus deaths—almost 14,000 people. And while the U.K. is struggling to determine how many virus-related deaths have occurred in care homes, the National Care Forum estimated that they doubled in just one week in April.

“It's unbelievable that it's taken so long to get the data sorted out,” said Martin McKee, professor of European public health at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. “Without good data, I can't actually understand how you can even start thinking about opening up.”

In Milan, the epicenter of the Italian epidemic, police last week raided the 1,000-resident Pio Albergo Trivulzio in a criminal probe into more than 200 virus deaths in the nursing home, according to people familiar with the matter. Managers at the publicly owned facility, the country’s biggest, are suspected of hiding virus-positive patients, said the people, who asked not to be named because the investigation isn’t public.

“I saw tears and fear in my colleagues’ eyes,” said Stefania Martini, a technician at the home who is now in quarantine. Management warned staff against wearing masks “because we might scare patients, creating a false sense of emergency,” Martini said. A spokeswoman for the facility declined to comment.

Even in Germany, where the virus took longer to spread into facilities for the elderly, between one-third and one-half of all virus deaths have been linked to care homes of some kind. Once below 1%, the German fatality rate for the virus has crept above 3% as it spreads through nursing homes, according to the Robert Koch Institute, the country’s public-health authority.

Germany’s lower death rate may be because relatively few elderly Germans live with their families, said Jennifer Dowd, an associate professor at the University of Oxford. In southern Europe, by contrast, there’s greater cross-generational contact, with grandma or grandpa more likely to bunk in a spare room.

“In countries where the older population is more physically and socially separated from working-age people, it might actually take longer to reach those vulnerable populations,” Dowd said. “Once it’s in, it’s obviously a disaster.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.