The Virus Isn’t the Only Problem for Germany’s Nose-Diving Economy

Nose-Diving German Economy Isn’t Just Suffering From Virus Woe

(Bloomberg) -- Just as Germany starts counting the cost of the coronavirus’s damage to economic growth, officials will get another glimpse of the shaky foundations it was built on.

Gross-domestic-product data this week will reflect not only how Europe’s biggest economy began a nosedive in March, but also that its stalling engine was already in need of repair -- a legacy of Chancellor Angela Merkel’s rule that will probably outlast the outbreak.

While the virus-induced crash in activity may temporarily drown out any narrative of neglect, it might not silence observers who had long pushed for a large-scale budget stimulus to reinvigorate growth that was outpaced last year by all major euro-area peers, apart from Italy.

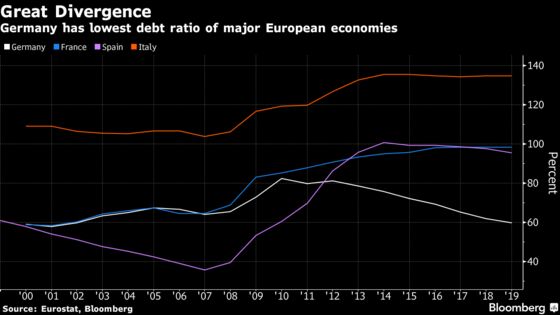

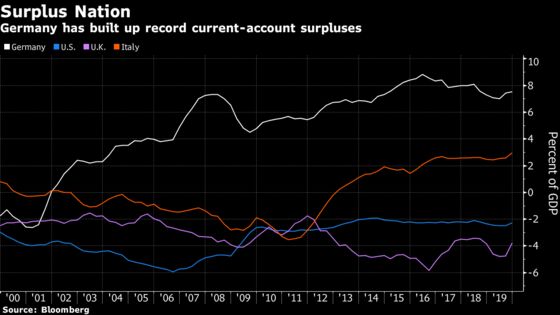

Spurred on by a debt-averse public, Merkel’s government zealously avoided such spending, even when it could borrow money for virtually nothing. Finance officials, whose budget package to combat the pandemic fallout is second only to the U.S., claim the space for stimulus now vindicates their reticence. But many economists say Germany could easily have afforded more investment beforehand.

“The fiscal consolidation over the last 10 years has not increased our ability to weather this crisis,” said Christian Odendahl, the Berlin-based chief economist at the Centre for European Reform. “We refrained from going on a massive spending spree or lowering taxes massively. For the health of the European and world economy, we probably should have done both.”

While lockdown measures to contain the virus only took effect in March, the damage for the whole first quarter will be eye watering. Data on Friday may show the economy that is Europe’s motor shrank 2.3%, the most since the 2009 global financial crisis.

The European Commission predicts a contraction of 6.5% this year, enough to be Germany’s worst postwar slump. Federal tax revenue may fall short by 50 billion euros in 2020, Eckhardt Rehberg, budget spokesman for Merkel’s CDU/CSU group, told ARD television on Thursday. Still, the economic contraction isn’t as bad as that faced by other euro members such as Italy or Greece.

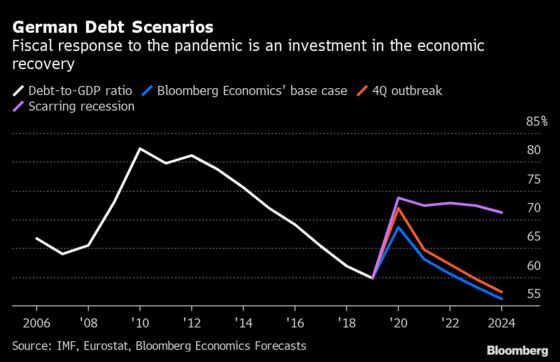

“We expect far less scarring to the economy than to many others in the euro area,” said Jamie Rush, chief European economist for Bloomberg Economics, in a note published on Thursday. “Still, there’s a risk that it slumps again on a second outbreak, or that government support efforts fall flat.”

Officials have deployed hundreds of billions of euros in stimulus and aid, with measures ranging from furloughs for workers to loans and guarantees for businesses.

Germany’s Virus Package |

|---|

|

But growth was already in trouble, with Germany eking out the slowest expansion in six years in 2019, and many analysts reckoned stimulus was warranted well before the coronavirus. Its export-reliant model took a battering amid the U.S.-China trade dispute, while the auto sector, reeling from the emissions-cheating scandal, struggled with a global shift to electric engines.

Germany’s industrial sector projects a revenue drop of 24% on average this year, according to a survey of 1,402 companies by Gesamtmetall on Thursday. The employer’s group urged the government to implement a program to stimulate demand.

“Germany tends to suffer from global economic shocks, and that’s what we saw last year,” said ABN Amro’s Nick Kounis. “It seemed odd to everyone apart from German economic policy makers that there was this underinvestment in Germany, given that they could finance so cheaply and that these investments would return more than the cost of the financing.”

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say

“Berlin’s balanced-budget straitjacket has long-resisted the efforts of fiscal progressives, European leaders and ECB presidents to unpick it. That makes the force with which it was thrown off as the coronavirus struck all the more remarkable.”

--Jamie Rush. For his GERMANY INSIGHT, click here

That it was less odd in Germany was also because of local conditions. A constitutionally enshrined debt brake -- with an exception built in for crises -- and a habit of balanced budgets, supported by voters, meant any shift in stance would take time.

Finance Minister Olaf Scholz began fiscal easing last year with incremental steps focused on green initiatives, but the government resisted pressure for a major stimulus.

Leading those calls was the International Monetary Fund, which said the country needed investment and tax cuts to lower its current account surplus and aid its own economy. The European Central Bank also sought fiscal easing, while not citing Germany by name.

Germany has trailed Britain and France on information technology and infrastructure spending for years, according to the OECD. Its national railway service is notoriously unreliable, and the country is outranked by some neighbors on mobile phone connectivity.

Longtime domestic critics of Germany’s fiscal stance include Marcel Fratzscher of the DIW Institute in Berlin, a former ECB official who observes that the lack of outlays on aging capital stock such as buildings or roads means state investment has actually been negative for years. Municipalities last year cited a 138 billion euro ($150 billion) spending shortfall, with schools, streets and administrative offices top of the list.

“If it creates more economic dynamics, it finances itself,” said Fratzscher. “Had they done more investment, Germany would have had exactly the same ability to react to the crisis as today.”

One caveat to that narrative was repeated in a recent report by Germany’s Council of Economic Experts, who noted that dilapidated buildings and roads aren’t the result of a lack of funding, but rather construction bottlenecks and bureaucracy. And the crisis has underscored Germany’s hospital provision to be world class.

Whatever the underlying challenges, they will need addressing soon if the country -- and even the wider region -- wants to avoid falling by the wayside of global growth. The all-important auto sector, for example, stands to lose 100,000 jobs as part of the shift toward lower emissions, according to labor union IG Metall.

Restoring the economy might require more than just money, but rather a new vision from Merkel or a successor replacing her later next year. In the meantime, the country can still take some comfort.

“Maybe higher investments would have made Germany more resilient, maybe it should have cut taxes, or become less dependent on foreign demand and cars,” said Christian Schulz, director of European research at Citigroup. “These are all valid arguments to be had. But fiscal space seems to be a luxury in this crisis.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.