No Junk Debt Is Too Risky: How Fed’s Bailout Changed Everything

No Junk Debt Is Too Risky: How Fed’s Bailout Changed Everything

(Bloomberg) -- Long before the coronavirus pandemic would bring business to a standstill all across America, Surgery Partners Inc., a sprawling network of outpatient clinics, already had its share of financial problems.

This was no secret on Wall Street. Surgery Partners’s majority owner, the buyout firm Bain Capital, had loaded so much debt onto the company’s books that when it went to the market last year to refinance maturing bonds, investors demanded a 10% interest rate to compensate them for the risk. The debt was rated CCC -- eight levels below investment grade.

Even a moderate downturn, it was understood, was going to raise existential questions about the company. So by late March, with the economic effects of the outbreak in full force, frantic investors braced for default, pushing the price of those bonds below 55 cents on the dollar.

But then the Federal Reserve did something it had never done before. It pledged to buy risky corporate debt as part of its emergency financing package for the economy. The move was so aggressive and sparked a rally that was so powerful and broad-based that today those bonds are all the way back up near par value, and Surgery Partners was able to raise another $120 million from loan investors earlier this month.

It all has worked out so fortuitously for the creditors and equity holders of Surgery Partners -- and those of scores of other companies with similarly shaky balance sheets -- that the Fed’s actions carry a grave risk: that investors, rather than being chastened, will be emboldened to take greater chances and seek fatter returns in the future, believing that policy makers will be there to bail them out if they get in trouble.

Economists refer to this phenomenon as moral hazard, and it hasn’t been this big a concern in a long time, perhaps not even during the 2008 financial crisis.

“It’s an exquisite irony,” said Nathan Sheets, chief economist of PGIM Fixed Income. “What the Fed is doing is necessary to get the markets going again, but on the other hand they leave investors thinking the Fed has their backs.”

Decade of Warnings

That’s not to say the Fed’s policy approach doesn’t have its merits. In fact, it may well have helped avert another financial crisis and possible economic depression. But there are also very real, significant risks that come with such an aggressive response.

The central bank had spent more than a decade telling the public that it was unwavering in its resolve to force Wall Street to rebuild its capital buffers so it could lend both in good times and bad. Yet even after banks beefed up their reserves and cut back on risk-taking with their own funds, the financial system is yet again in need of extraordinary support.

“It’s as if they believe the banking system no longer works,” said Paul Tucker, former Deputy Governor of the Bank of England and chair of the Systemic Risk Council, a think tank of former regulators.

What’s worse, according to Tucker, is that the Fed might have altered investor incentives for years to come, creating even more instability in the next downturn.

A spokesperson for the central bank declined to comment.

Moral hazard risks are hardly confined to the universe of Wall Street creditors.

At a time like this, when trillions of dollars of taxpayer money are being pumped into the economy and financial rules are being rewritten to provide additional relief, these risks pop up everywhere -- from the bankers and private-equity executives who loaded their companies up with too much debt to homeowners who took on bigger mortgages than they could afford and even to, according to President Donald Trump and his allies, some states that ran big budget deficits and are now seeking federal aid.

The Fed program, for its part, was designed to be targeted in its scope. The central bank said it would buy junk debt only of some companies that recently lost their investment-grade status. Its purchases of collateralized loan obligations, which are in turn the biggest buyers of leveraged loans, will be limited to a small set of the securities.

And even the loans that the central bank will help originate directly have restrictions on leverage that will likely leave out many private-equity owned companies.

Yet what’s transpired since the expanded plan was announced on April 9 is that none of the fine print really matters, at least not now. Markets are rallying even though the Fed has yet to formally set up the facilities through which it will make the purchases or extend new loans. There is also confusion as to which companies would even qualify.

“The signaling effect of what the Fed is doing is powerful,” said Jack Janasiewicz, a portfolio manager at Natixis Advisors. “It was enough to shift sentiment, and when we start to feel better about things, we start buying. Worst-case scenario, if things really fall apart, the Fed will step in.”

Junk Revival

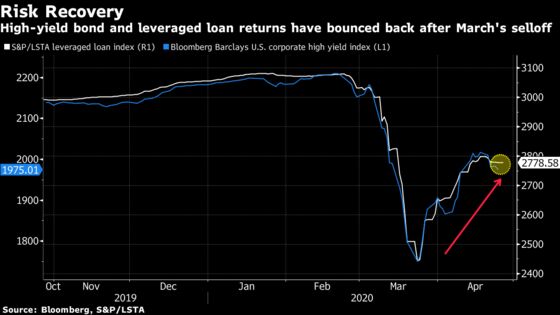

Junk bonds have already recovered roughly half of the losses they suffered during the recent sell-off, while the leveraged loan market is also on the mend. Speculative-grade bond issuers have sold more than $34 billion of debt so far in April, one of the busiest months in recent years.

Companies whose business have been ravaged by social-distancing measures adopted to contain the spread of the coronavirus such as SeaWorld Entertainment Inc., AMC Entertainment Holdings Inc. and Gap Inc. have all successfully tapped bond investors to boost liquidity.

As a result, default rates may not rise as much as initially expected, according to analysts from JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Morgan Stanley.

Some bankers who arrange debt deals for junk-rated companies and their private equity owners are encouraging even riskier borrowers to access the market while the times are good. That would allow buyout firms to sidestep more difficult bank financings or more expensive equity capital injections, which many see as anathema.

Surgery Partners got enough interest from leveraged loan buyers for 10 times the amount it was seeking to borrow earlier this month. While it still paid a punitive yield of over 9%, that was well below the more than 12% it had initially marketed.

A representative for both the company and majority owner Bain Capital declined to comment.

Everyone Wins?

The Fed’s decision to wade into certain high-yield, high risk junk-bond ETFs is one of the more controversial steps taken by Chairman Jerome Powell. Depending on the securities it buys, the move could expose the central bank not just to high quality speculative-grade issuers, but also to corporations on the cusp of bankruptcy.

After years of risky companies taking on unprecedented amounts of debt, weakening lender safeguards and blurring earnings math to appear more credit worthy, some now argue the Fed is turning everyone into a winner, distorting asset prices in the process.

“Once you start fixing prices, the information content is lost and they no longer tell us anything about risk and reward to help allocate resources,” said Peter Fisher, a professor at Dartmouth College’s Tuck School of Business and former head of fixed income at BlackRock, which is managing some of the Fed lending facilities.

Even more troublesome is that the Fed had been warning for more than a year about corporate leverage buildups amid the record economic expansion.

In a financial stability report published last year, the central bank noted that the share of new loans to large corporations with debt-to-earnings ratios above 6 times had increased past peak levels previously seen in 2007 and 2014 when underwriting quality was poor.

Distorting Incentives

Srinivas Dhulipala, a former prop trader at Bank of America Corp., said he shuttered his hedge fund last year after falling behind rivals partly because he was unwilling to take outsized risks on his credit bets. He believes the Fed is distorting incentives in the marketplace.

“The Fed is saying if you were willing enough to take too much risk, then don’t worry, we will bail you out,” he said in an interview. “Of course the virus was a big hit,” he added, but the market “was trading with absolutely no cushion for any type of a shock.”

Matthew Mish, a strategist at UBS Group AG who has often highlighted risks building in corporate debt, has a more generous assessment of Powell’s actions so far. He argues the central bank needed to prevent an economic crisis from turning into a financial one and that the benefits filtering through to the riskiest borrowers have so far been minimal.

“What I am concerned about is if the Fed ultimately has to expand the credit box, because the next time they expand it is going to be bailing out highly levered, private-equity owned companies,” Mish said. “That would be the definition of moral hazard.”

For some, that bridge has already been crossed.

“If they now provide a significant amount of support to get those firms that were heavily leveraged through this, everybody will assume that they will do it next time,” said William English, the former director of the Division of Monetary Affairs at the Fed Board who is now a professor at the Yale School of Management. “They will have to be clear that they are only doing this with gritted teeth.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.