Netflix’s ‘Bloodbath’ Reputation for Canceling Shows? It’s Overblown

With such a huge budget, Netflix only looks like it’s pulling the plug sooner.

(Bloomberg) -- Just a few months after TV critics anointed “Tuca & Bertie” one of the best TV shows of 2019, series creator Lisa Hanawalt got the bad news: Netflix Inc. wasn’t ordering a second season of the animated comedy.

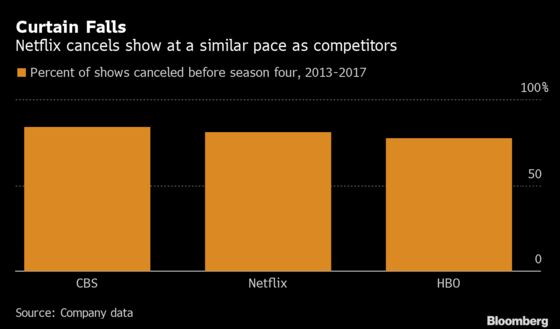

The show was one of two dozen that the streaming giant has canceled this year — a large number that left many in Hollywood grumbling. Yet as it turns out, Netflix is no quicker to drop shows than other networks, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. It’s the company’s huge programming budget — forecast to top $14 billion this year — that makes cancellations loom large.

Of the English-language scripted programs that debuted on Netflix from 2013 to 2017, about 19% lasted more than three seasons. That puts the company squarely in between CBS, the most-watched U.S. TV network, and HBO, the most-popular premium cable network. Almost 50% of Netflix shows made it to season three, again comparable to HBO.

The frustration with Netflix illustrates that Hollywood is still coming to grips with the company’s new way of doing business — and the less-than-transparent data behind its decision-making. Competing networks order pilot episodes to determine a show’s potential. And they don’t churn out the same volume of shows as Netflix, so it’s easier to forget their cancellations. The same year HBO released “Game of Thrones,” it introduced a trio of programs that lasted only a couple seasons. Until a few years ago, Netflix had never made a TV series.

Netflix bases its decisions on numbers just like most TV networks. But the metrics differ from the usual Nielsen data shared widely in the industry, according to Netflix employees, TV producers and executives who’ve worked with them. And unlike traditional broadcasters the company doesn’t provide much information about what drives decisions.

The company declined to comment for this story, but Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos says Netflix is changing. “We are being much more transparent with creators and increasingly with the public in terms of what’s being viewed on Netflix,’’ he said earlier this month. “I think people use a lot of different inputs to figure out what they want to see, and popularity is definitely one of them.”

Netflix does judge programs based on the number of viewers and how much time they spend watching a show. But that’s only part of the equation. It uses its own calculation — dubbed efficiency — to measure the value of a show relative to its cost. The longer a show is on the air, the higher the cost and the higher the hurdle for renewal.

The popularity of most programs on the streaming service peaks in season one and falls thereafter — sometimes sharply. The majority of Netflix shows end after two or three seasons.

Netflix has historically prized shows that attract subscribers, since the company’s primary goal is signing up new users. When viewers watch a particular show in their first month as customers, it suggests that program drew them in. Netflix also values shows more if viewers finish a season or don’t stray to other programs.

Seasons two and three are key dividing lines for another reason. Customers who subscribe to Netflix for a couple years are far less likely to cancel than those who are new. Thus, shows that have lasted a couple seasons have already served their purpose of securing a long-term user.

Netflix could placate producers — and the agents who make their deals — by sharing more information. But the service is commercial-free, and the company argues such numbers only matter to advertisers who buys spots based on the size of a show’s audience.

As a result, show creators often have few insights into who watches what when they sit across the table from Netflix executives. The company gives them some news but not the full picture. Still, in some cases it will deploy data to lure someone it really wants, like producer “American Horror Story” producer Ryan Murphy.

Not everyone objects to the lack of data. “I’m thrilled I got to tell stories I wanted to tell without any hindrance,” said Neal Baer, who produced “Designated Survivor,” a thriller featuring Kiefer Sutherland. “It’s such a numbers game, out of my control.”

Netflix acquired the rights to the show after it was canceled by ABC, which aired the first two seasons. Baer oversaw production of 10 more episodes — about half the number of a season on ABC — and was allowed to take more risks with the storytelling.

Netflix officials are sensitive to criticism that the company isn’t as talent-friendly as some rivals, and in recent years has held viewership update calls with producers and outside studios, and released some viewership data publicly. The Emmy-nominated “When They See Us,” about young black men falsely accused of a brutal attack in New York’s Central Park, was seen by 25 million households in its first four weeks, while the dramedy “Dead to Me’’ was watched by 30 million over a similar time span. But Netflix doesn’t offer such numbers for all its programs.

Executives who work with Netflix say the company’s strategy changes quickly, and that the cancellation data may look far different in a few years. Still, with a budget that dwarfs the spending at other networks, Netflix will be delivering more bad news to show creators and fans who feel their favorite programs died too soon, even if the company’s cancellation rate stays close to those of competitors.

The decision to drop “Tuca & Bertie” confused critics and viewers, including one fan who started a petition to save the show and collected more than 25,000 signatures. Subscribers have mounted similar campaigns for “Santa Clarita Diet” and “One Day at a Time,” two more casualties of what one media outlet dubbed a bloodbath.

“I still get daily messages and tweets from viewers who connect personally to the characters and stories,” Hanawalt wrote on Twitter. “None of this makes a difference to an algorithm.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Rob Golum at rgolum@bloomberg.net, Nick Turner

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.