The Woman Fixing Puerto Rico’s Finances Knows Not to Waste a Crisis

The Woman Fixing Puerto Rico’s Finances Knows Not to Waste a Crisis

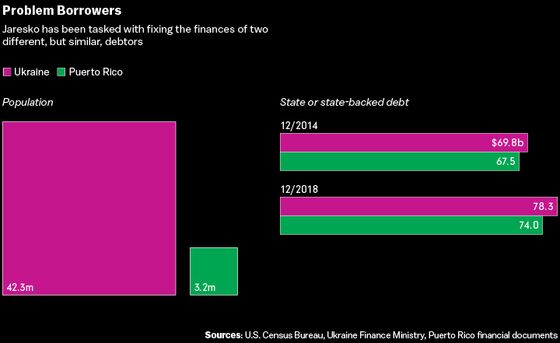

(Bloomberg Markets) -- Natalie Jaresko, who’s helping manage Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy process, knows more than most about the risks government borrowers can face. The Chicago-area native lived in Ukraine for 25 years, where she co-founded a private equity firm and then served as minister of finance, overseeing the country’s debt restructuring and its International Monetary Fund program as war drained its resources.

In early 2017 she agreed to move to Puerto Rico to lead the federal oversight board tasked with reducing the commonwealth’s $74 billion in debt and $50 billion of pension liabilities. Months later, Hurricane Maria slammed the island, ripping apart its electrical grid and killing thousands.

Jaresko, who turns 54 in April, talked with Bloomberg News’s Michelle Kaske about how governments and investors should think about debt and risk.

MICHELLE KASKE: How do you compare the financial crises in Ukraine and Puerto Rico?

NATALIE JARESKO: Despite the fact that Ukraine has 10 times the population of Puerto Rico, or more, the two economies are about $100 billion each. The debt stack was very similar, $74 billion, $70 billion, each. So the size of the problem was very similar. The nature of the debt is very, very different.

Sovereign debt restructuring is a little more flexible, a little more dependent on the sovereign itself, whereas in Puerto Rico there are a wide variety of rules, regulations, and laws that need to be abided by in each of the debt restructurings. Puerto Rico is just more complex in the debt stack itself. There’s secured debt, there’s unsecured debt, and there are major differences with regard to priority.

MK: And they each had catastrophes: In Puerto Rico it was a hurricane, and in Ukraine there’s the war.

NJ: Those added to the debt crisis. In the case of the war, 20 percent of GDP literally just went away. It was physically in the occupied territories, the 7 percent of the geography that was occupied. In Puerto Rico’s case the entire electricity system goes down. It’s a very, very weak fiscal situation then made a hundred times worse by war in Ukraine and a hurricane in Puerto Rico.

MK: Even if you take away Puerto Rico’s debt and its pension obligations, it’s still a structure that’s faulty. For years they’ve borrowed to fill budget gaps.

NJ: That’s the case in both. I would argue that that’s the case in many of the other sovereigns as well, like Greece. So you have a fiscal set of challenges, which is the nature of your spending and the fact that you have access to debt and you never really make the difficult choices. Puerto Rico did that for a decade or more. Ukraine was doing that.

MK: You grew up in the Chicago area but lived most of your adult life in Ukraine. What was it like moving to a Caribbean island and living through Hurricane Maria?

NJ: What drew me to Puerto Rico was the ability to use the skills and the experience that I had in Ukraine, having accomplished both the debt restructuring but also the fiscal rebalancing, even at a time of war when we had to spend more on national security.

I grew up as the child of immigrants that came out of the Soviet-World War II-Nazi experience and really had a great deal of confidence in the U.S. system. That you can come on a boat with nothing and work hard—both of my grandmothers were illiterate, signed their names with Xs—yet I went to Harvard graduate school. That story of being able to build a life, a middle-class life, and that the U.S. gave people that opportunity, at least at that time, really lingered with me. It’s why I went to the Kennedy School of Government. I believed in JFK’s “Ask not what your country can do for you but what you can do for your country.” And I also believe that the model works, that a strong middle class is the pillar of democracy and the pillar of a strong budget.

MK: What are some of the lessons from Ukraine that could help Puerto Rico?

NJ: Don’t waste a crisis. The political will to take difficult steps and to make change is most available when the political class feels that there’s a crisis. The second big lesson is that you need champions. Each of these reforms is extremely difficult. You need someone to inspire and to infuse people with this sense of “we’ve got to do it now, there’s no time to wait.”

MK: Is anyone on the island doing that?

NJ: When you look at where we’ve come with the reform of the electricity sector, the Puerto Rico Electric Power Authority, I think Governor Ricardo Rosselló, Christian Sobrino [executive director of Puerto Rico’s Fiscal Agency and Financial Advisory Authority], Omar Marrero [executive director of the island’s Public-Private Partnerships Authority], and others at Prepa itself are infused with “this is a singular opportunity to do massive change in the electricity sector.” We need more private-sector involvement. It’s a big mind-change. A big societal change.

MK: Corruption is an issue for many places, including Ukraine. What about Puerto Rico?

NJ: It is a major issue in Ukraine. It is an issue in Puerto Rico. Ukraine still suffers from, unfortunately, a lack of rule of law and a court system that is not free and fair, therefore there’s not a system of retribution for your actions. In Puerto Rico we have a court system and we have rule of law. What we have in Puerto Rico is a history of nontransparency in certain contracts. It’s not unlike cities in the U.S. You don’t have the same visibility with regard to how contracts come to be. What is the process for procurement?

MK: After restructuring $17.6 billion of Puerto Rico’s sales-tax bonds in February, the focus now is on reducing $17.8 billion of general obligations and commonwealth-guaranteed debt. What are some of the challenges?

NJ: The challenges for the commonwealth debt will be assuring debt sustainability is maintained throughout this process. It’s in no one’s interest for Puerto Rico to be bankrupt or to face a default 7 years from now or 10 years from now. We’ve always approached it as a once-and-done debt restructuring. You also have a big issue with pensions, a $50 billion pension hole. That’s another difference with Ukraine. Pensions were not looked at as debt in a sovereign situation but they are in a U.S. bankruptcy. It will be complex.

MK: The board earlier this year asked the court to declare debt sold in 2012 and 2014 as invalid, as it believes those bonds violated constitutional debt limits. How has that affected negotiations?

NJ: It makes it more complicated. Many holders hold some of each and so it’s not like we have a clear division between them and the others. Many of them hold cross holdings in different vintages.

MK: How does Puerto Rico regain the market’s trust?

NJ: The academic answer is to issue bonds that are well traded, well priced. To be able to provide timely and accurate financial data, including audits. The practical answer is that markets tend to trust actually too soon after restructurings, in my opinion. If liquidity is available in the marketplace, triple tax-exempt bonds will attract buyers. And so I’m not as worried about when can we issue new debt—although that is critical and part of our mandate. What I want is to be able to have access, to be rated to have access, but not necessarily to be borrowing more.

MK: Were the investors at fault for helping to create such a huge debt load?

NJ: You could argue both sides are responsible. In the case of Ukraine, there were no audits. In Puerto Rico, they were behind in their audits. Why didn’t financial investors demand them before issuance? In Ukraine, corruption was a big issue for a long time, and everyone was well aware of it. In Puerto Rico, I think everyone was well aware of deficit spending. To some extent they all knew what they were buying.

MK: How should countries avoid piling on debt during economic downturns and becoming the next Ukraine or Puerto Rico or Greece?

NJ: The first thing is not to use debt as the sole solution. Debt used to cover operating expenses is always dangerous. Capital borrowings ought to be used primarily for capital investments, long-term investments that have an economic payback. The world is extraordinarily competitive. Businesses get up and move. People get up and move. Once you’ve lost the confidence of the population, it’s very hard to bring them back.

MK: Does the island need federal tax breaks to come back to help the economy grow?

NJ: A tax system is most competitive if you have low rates, very simple administration. I tried to do a major tax reform in Ukraine, but only parts of it got adopted. Countries like Georgia, Estonia, Slovakia that moved to very, very low rates without the complications of deductions, preferences, privileges, and credits tend to be the easiest for doing business and the most competitive.

If the federal government goes ahead and restores some tax privileges, no one’s going to say no to that. But I don’t think we should rely on them, because we fail to develop the other parts of the economy, and over time it won’t be enough. If you don’t have a qualified, well-educated, well-suited labor force, there’s a limit to what tax privileges will accomplish over time.

Kaske is a municipal-bond reporter for Bloomberg in New York who’s been covering the Puerto Rico bankruptcy.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Christine Harper at charper@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.