(Bloomberg Opinion) -- With oil crashing below $25 Wednesday morning, the U.S. exploration and production sector is in critical condition already. Beyond the frackers and the majors, though, the double dose of coronavirus and OPEC disintegration is also tearing at the sinews that power it.

Oilfield services contractors were still dreaming wistfully of getting back to their pre-2014 health when 2020 rolled around. Halliburton Co., for example, will have to find a new nickname: “Big Red” now has a market cap of about $5.5 billion, down from roughly $50 billion two years ago.

Another sector is in danger of vanishing altogether: master limited partnerships.

Technically, MLPs aren’t actually a sector; just a particular financing structure that tends to be used for pipelines and other vital logistical bits of the energy business. Regular readers (hey, a man can dream) know I have one or two quibbles with the MLP structure, mainly due to its weak governance resulting in overleveraged companies with insiders and regular investors often at cross purposes — and evaporating unit prices. As investors have given up, particularly on the institutional side, many midstream companies have abandoned the structure altogether, becoming regular C-corps in order to tap a wider pool of money more comfortable with traditional governance and financial metrics.

Last September, I totted up the market cap and free float of a sample of 83 North American midstream firms (many of these companies, apart from the C-corps, have a significant sponsor shareholder). Just six months ago, it was striking that the entire sector had a collective market cap of only $575 billion, of which just $484 billion of was actually traded.

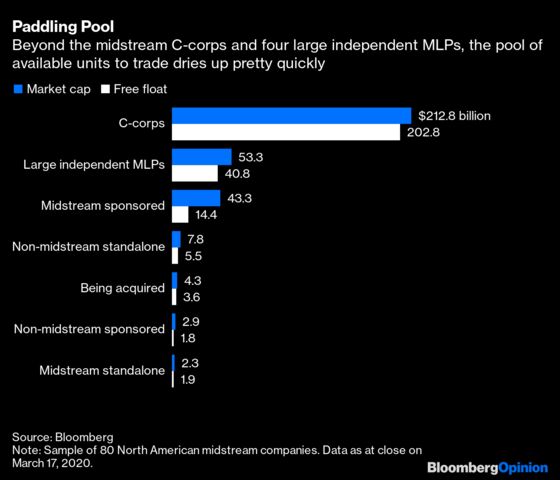

Golden memories, it turns out. Since then, a few companies have been acquired, so we’re down to 80. Their collective market cap as of Tuesday’s close: $327 billion. To give a sense of how small that is, it is only slightly bigger than the combined market cap of just three large oil producers, Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp. and ConocoPhillips — and that’s after their recent, massive sell-offs. The free float of the midstream group is a mere $271 billion. Moreover, C-corps dominate that, accounting for three quarters. You do the math on what that leaves for MLPs.

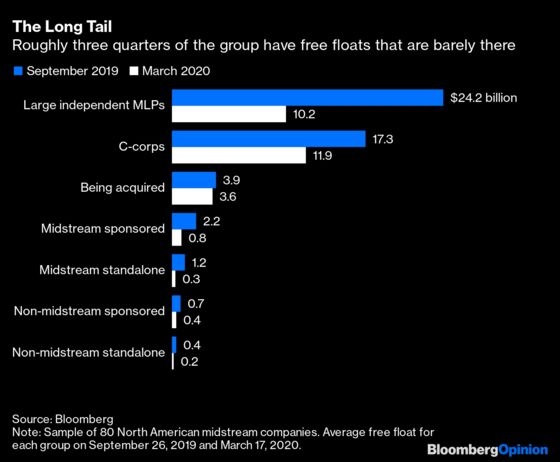

As firms have converted to more-liquid C-corps and the entire sector has dropped, the number of barely-there companies has risen. Six months ago, roughly half the group had an average free float of less than $600 million, already too small for any but the most dedicated money managers to bother with. Today, 58 of the group, or almost three quarters, have an average float of about $400 million.

There is a vicious cycle at work here, one which predated the latest crisis but has been amped-up by it. As liquidity in a lot of the sector dries up, so institutional investors are deterred even further, making it worse. At the same time, as bigger companies have converted to C-corps and been withdrawn from MLP indices, so the latter are rebalanced among the remainder — generally smaller companies with weaker performance, making the sector as a whole even less attractive.

It has been apparent for a while that the larger remaining MLPs, such as Enterprise Product Partners LP, should convert to C-corps and access a bigger pool of potential investors as their old pool shrinks. For various reasons, usually related to insiders’ control and the tax hit on their low-basis positions in the partnership, some have held out. Yet the collapse in valuations confronts both rationales with a simple question: How much do you really have to lose at this point?

Implacable as that is, change is hard. Just on Wednesday morning, Marathon Petroleum Corp. said it had concluded a strategic review of 63%-owned MPLX LP and decided to retain the MLP structure partly on the grounds it “will remain an important, through-cycle source of cash” for the parent. Against that, MPLX currently sports a distribution yield of 29% and has consistently yielded north of 10% since late September, way before coronavirus showed up and OPEC+ imploded.

The abrupt shift in oil supply and demand exposes the overbuilding that resulted from midstream’s earlier excesses. That doesn’t mean all assets are suddenly worthless. But the sheer uncertainty about the shape (and scale) of the U.S. energy business that will emerge from this crisis means midstream’s fight for capital, which it was losing already, has become even more desperate. It simply cannot afford to remain chained to a structure whose heyday was more than five years ago and is now evaporating in front of our eyes.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.