Manchin’s Favorite Clean-Energy Plan Could Be Obsolete Before It Starts

Manchin’s Favorite Clean-Energy Plan Could Be Obsolete Before It Starts

(Bloomberg) -- Winding along the mountainous highways of West Virginia and Pennsylvania can feel like a journey through time.

The jagged, dark outcroppings of rocks contain millions of years of fossilized, organic remnants. They also hold the key to a clean-energy future that Senator Joe Manchin has seemingly backed more strongly than any other. But it’s a bid that analysts warn is destined for extinction even before it’s started.

The idea is to turn the Marcellus shale basin into one of the country’s new hydrogen hubs, with $8 billion dedicated to the projects in the recently passed federal infrastructure bill. The funding, first introduced in a measure by Manchin, will mean massive factories scattered across the country, including some that turn fossil fuels into hydrogen. For the Democrat from West Virginia, it's a way to keep supplies flowing from his gas-producing state and the Appalachian region.

The only problem? By the time this infrastructure-heavy vision gets built, it may already be obsolete. There’s a cleaner way to make hydrogen that could soon be cheaper, too. Experts predict that within 10 years the process that turns natural gas into hydrogen won’t make much financial sense.

This is shale country, where livelihoods have long been intertwined with turning black rocks into fuel. Extravagant stone churches tower over small towns, relics from the prosperous coal days. Then came the natural gas era of the last decade. If Manchin is right, soon many of the factories in America’s industrial heartland could be powered by clean-burning, Appalachian-made hydrogen.

If not, it’s a plan that potentially leaves the region with another set of stranded assets and a hole for jobs.

Blue Versus Green

The plan envisioned by Manchin, chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee, relies on natural gas to make hydrogen, with the captured carbon emissions injected back underground. The process has been dubbed “blue hydrogen.” The infrastructure bill stipulates that at least two of the U.S. hydrogen hubs must be in regions rich in natural gas.

The cleaner way to make hydrogen uses renewable power to run a device called an electrolyzer that splits water into hydrogen and oxygen. The process gives off no greenhouse gases that need to be captured and stored.

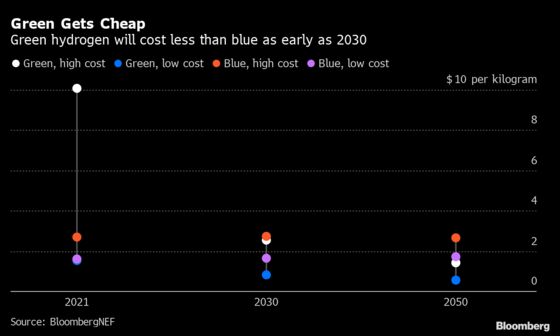

Such “green hydrogen” is currently much more expensive than blue, but BloombergNEF expects that to change – fast. Green could start undercutting blue as early as 2030, said Martin Tengler, a BNEF analyst.

“We are seeing green largely overtake blue from an economic perspective,” said Rachel Fakhry, a senior policy analyst at the Natural Resources Defense Council.

It would be a cruel twist in a region famous for booms and brutal busts. And Appalachia isn’t alone. The oil and gas industry is pushing hard for blue hydrogen as a way to keep gas wells pumping decades into the future. So are the communities where they operate. Last month, Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards and industrial gas company Air Products & Chemicals Inc. announced a $4.5 billion blue-hydrogen complex to be built in Ascension Parish, between Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

"The Appalachian region is a natural fit for a clean hydrogen hub," a spokesperson for Manchin said in an emailed response to request for comment. "The bipartisan infrastructure bill makes a significant investment to develop hubs that demonstrate the production, delivery and use of clean hydrogen.”

“Senator Manchin will continue to work with the administration to see these projects through,” the statement said.

On the Terminal: The Everything Guide to Understanding Hydrogen

Construction of the first wave of green hydrogen plants is already getting underway worldwide – including in such states as New York, Texas and California. Most blue-hydrogen projects remain proposals, years from opening.

The Democrats’ $1.75 trillion spending bill working its way through Congress also includes incentives for the production of hydrogen in the form of tax credits for both green and blue hydrogen. Manchin has yet to commit to supporting the underlying legislation and has thwarted some of its more ambitious climate initiatives.

While some price forecasts are less gloomy for blue hydrogen, most predict a similar trajectory to the one estimated by BNEF. Green will get cheaper as electrolyzer production scales up and renewable power costs come down. Blue will remain tied to the price of natural gas, which is unlikely to plunge.

“Eventually those assets will be undercut, like what is happening with coal in the power sector today,” said Tengler of BNEF.

‘Best Message Ever’

And yet, for many the allure of blue hydrogen is difficult to resist. It keeps alive the jobs now bound up with natural gas, well-paying positions that, if lost, would be difficult to replace.

“Our abundant domestic reserves of fossil resources can have a role in fuels of the future,” Manchin said in taped remarks at a July workshop on creating a hydrogen hub in the region’s Ohio River Valley. “I’m a strong supporter of an all-of-the-above energy policy and a firm believer in innovation rather than elimination, to use all of our bountiful resources in the cleanest way possible.”

In many ways, blue hydrogen is the embodiment of how President Joe Biden sees the energy transition: bullish on infrastructure, union-friendly and made in America.

“It’s the best message ever to tell people – that what we need to do to take care of our planet is exactly what we need to do to get everybody back to work and feeling good about living in the United States of America again,” White House National Climate Advisor Gina McCarthy said at the July event with Manchin. “As you can tell, I’m really excited about this.”

That message resonates in Appalachia, where the potential for a future without natural gas brings back memories of the devastating blow from the closure of coal mines.

Jobs Outlook

Pennsylvania State Senator John Yudichak, who backs the blue-hydrogen initiatives, said that when he was growing up near Nanticoke, not far from Scranton, the town had about 60 stores on Main and Market streets.

“By the time I graduated high school, they were all gone,” 51-year-old Yudichak said in a conference room decorated with hardhats and silver shovels commemorating projects developed during his time in office. “Bringing these communities back takes jobs.”

And what if green hydrogen outcompetes blue? “The market will decide,” Yudichak said.

Constructing a blue-hydrogen plant certainly would provide at least a temporary bump in employment.

Entrepreneur Perry Babb is working to build a blue-hydrogen production facility in Pennsylvania’s rural Clinton County, where job opportunities are few. The plant, he predicts, would employ 150 people after it’s built. The project still needs financing and permits, and likely won’t be in operation until 2025, he estimates. He argues that if the U.S. truly shifts to a hydrogen economy, demand for the fuel will be so great that both green and blue will have a place.

“Let’s make as much green and blue hydrogen as possible, because the scale of hydrogen needed is mind-boggling,” said Babb, chief executive officer of the KeyState to Zero project. “It’s going to have a huge impact on housing and workforce development.”

U.S. Steel, EQT

There’s no formal plan on the table for an Appalachian hydrogen hub, but companies are exploring the idea. U.S. Steel Corp., based in Pittsburgh, signed a memorandum of understanding in June with Norway’s Equinor ASA to study creating a hydrogen hub. The metals company, long a pillar of the local economy, has set a goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050, but is still figuring out how to get there.

“We need to reimagine how we make steel,” said Richard Fruehauf, U.S. Steel’s chief strategy and sustainability officer. “This used to be, still is, and hopefully will be the manufacturing center of the United States, and it’s got all these energy resources.”

The nation’s largest gas driller — EQT Corp., also headquartered in Pittsburgh — wants to build a blue-hydrogen production plant as part of a $75 million effort to invest in new technologies. CEO Toby Rice estimates that using Marcellus gas, he can produce the fuel cheaper than any green hydrogen plant, now and for years to come. Although neither green nor blue hydrogen is currently made at truly mass scale, the U.S. Department of Energy estimates green hydrogen today would cost about $5 per kilogram. Rice contends he can make blue hydrogen for less than $1 per kilogram.

“People also made a prediction that renewables were going to completely eliminate fossil fuels, and I think what we’re seeing in the world right now is a clear sign that we still need fossil fuels,” he said. “So I put some of it in that camp.”

For Warren Faust, a former metalworker who’s now president of the Northeast Pennsylvania Building and Construction Trades Council, the bottom line is all about jobs. He can easily tick off the workers needed to build the machinery inside a blue-hydrogen facility: boilermakers and pipefitters, asbestos workers, sheet-metal workers.

“That’s not even counting the crane worker, the laborer and the electrician,” he said. “That’s seven trades right there.”

But green hydrogen plants, currently under development by such companies as Plug Power Inc., would need tradesmen, too.

“I don’t care green or blue,” he said. “I just care about building a project.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.