The Weekend Destination That Mexico City’s Creative Class Prefers

Malinalco is a popular weekend getaway among artists and musicians from Mexico, but its superlative waterfalls are little known.

.jpg?auto=format%2Ccompress&w=200)

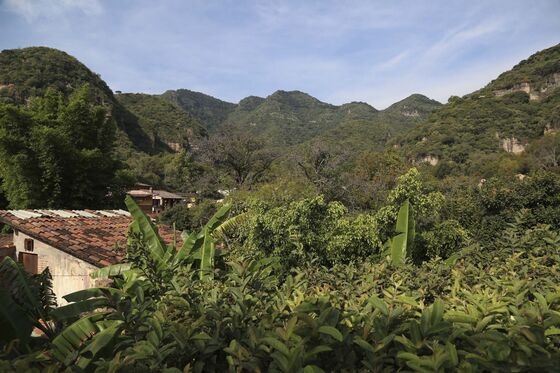

(Bloomberg) -- If you stand in the middle of Malinalco’s central plaza—a pastoral square surrounded by sheer volcanic rock faces cloaked in flowering subtropical forest—it’s hard to imagine that Mexico City, the hemisphere’s largest metropolis with some 20 million people, lies just two hours away by road.

But though Malinalco is a popular weekend getaway among artists and musicians from the capital, its superlative waterfalls and colonial chapels and a magnificent Aztec ruin are little-known to most foreign visitors.

It’s also the closest place for travelers from Mexico City to taste mezcal in a place it’s made. Since 1994, strict (and controversial) laws have determined who could legally call their agave distillates mezcal, based in part on geography. Though distillates of agave are produced throughout Mexico, for years the denomination of origin (DOC) for mezcal was limited to just nine states.

In September, the DOC was extended to include 12 municipalities in Mexico State, the country’s most populous state, all clustered around Malinalco. The formal recognition has started to draw new attention to producers who have been making distillates of agave for generations and can now legally label them mezcal after certification. This is important symbolically as a formal acknowledgement of a producer’s craft; more important, it makes marketing the product easier.

Visitors to Mexico City, who often fly down for less than a week, often lament how little time they have to explore this vast and beautiful country. Though two days is a short time to experience all that Malinalco has to offer, a weekend here gives a glimpse of many Mexicos in one impossibly picturesque place.

The Back Story

Before the arrival of the Spanish, the area now occupied by Malinalco was an important ritual center for the Aztec Empire based in Tenochtitlan, now Mexico City. Carved from the cliffs that look out over the spires and terra cotta rooftops of the colonial village, the archaeological site of Cuauhtinchan was built around the turn of the 16th century, late in the period of Aztec dominance in Mesoamerica.

It was primarily used for the initiation rites of elite warriors. The monolithic central temple and the surrounding foundations of other structures, first excavated and restored in the early 20th century, make up a fraction of the entire site. Not far from the entrance, the Luis Mario Schneider Museum conserves artifacts unearthed in the surrounding region and contextualizes them within the history of the Aztec Empire.

As they did in many places of ritual importance for pre-Hispanic cultures, the Spanish invaders wasted no time in building rival centers of religion and power in Malinalco, filling the valley below the Aztec temple with churches and chapels, foremost among them an Augustinian monastery built in 1543.

Indigenous painters filled the cloister with elaborate black-and-white murals that cover the walls like ivy. Monkeys pluck cacao pods from winding branches while tlacuaches (an endemic opossum) play in the shade of cacti growing wild around the medallions emblazoned with the complex iconography of the Catholic Church—an early example of the mestizaje, or cultural mixing, that eventually produced the singular culture of modern Mexico. Though the main chapel was heavily damaged during the September 2017 earthquake, the most impressive murals have already been restored.

On weekends, when the village fills with visitors, shops fill the parallel streets that lead from the plaza to the entrance of the archaeological site. On Vicente Guerrero Street, spots such as La Tienducha and Xoxopaxtli sell hand-loom scarves, leather sandals, and baskets woven from palm. On Avenida Hidalgo, purveyors sell antiques and traditionally painted ceramics, while Mondo, which shares a small, picturesque plaza with the Chapel of Santa Monica, offers sculptural pottery and jewelry from contemporary Mexican designers.

The Mezcal

But you’re probably coming for the mezcal. It’s never been difficult to get a good one here: Even before it got its own denomination of origin, hastily hand-painted signs would dangle from doorways and gates to advertise “Mezcal para llevar”—mezcal to take away—or “Mezcal Tradicional.” If you knocked on doors and asked for a taste, you could sample whatever the family had on hand, usually from their own land or fro m that of a family member producing in the hills above town or farther down the valley, near the neighboring state of Morelos.

Those signs still turn up all over town. You should stop whenever you see one to taste for yourself how much mezcal can vary—even in a region of limited production that uses only three varieties of agave—from producer to producer and village to village. If you taste some you love, you can buy a liter to take home in a repurposed soda bottle for about 200 pesos ($10).

In the past few years, as mezcal-producing villages around Malinalco started the long process of official DOC recognition, purveyors around town have begun stocking local mezcal. Restaurants such as La Casa de Valentina and Los Placeres buy their supply from producers in the village of Palmar, whose families produce throughout the year. The gift shop of Museo Vivo, a hands-on museum of native bugs and reptiles that’s great for kids, sells small bottles produced by a family in the small hilltop village of El Zapote.

At La Tienducha, an eclectic shop in a 16th century house near the Chapel of Santa Monica, owner Agustín Fonseca offers tastes of the mezcal he sells by the liter to anyone who stops in to browse his quirky stock of dried herbs—Malinalco has a long tradition of herbal medicine—and hand-carved kitchen tools. His spirits are sold alongside the quotidian merchandise of your typical corner store: votive candles, canola oil, and Maruchan noodles. It’s easily the most charming shop in town. If you speak Spanish, expect to while away a half-hour in conversation with the talkative Fonseca.

Less than a block away, Casa Diablitos serves mezcal that the three siblings who own it produce on their property in the humid lowlands near the border with Morelos. Made from agave criollo (a local variety similar to espadín, which is grown widely throughout the country) and from the rarer cupreata variety most often found in Guerrero, Casa Diablitos mezcales are gentler than those made in the cooler villages just outside Malinalco and are ripe with flavors of tropical fruit.

A few blocks away, in a gazebo-like building nestled at the foot of the mountains amid banana trees, Palmezcal is part bar, part concert venue, part research center for regional agave distillate, and all passion project for owner Rafael Rebollar, a singer with white muttonchop whiskers. He and his spouse run the place with the enthusiasm of hosts at home, serving an outstanding mezcal from Palmar along with simple snacks Rebollar whips up in a small, open kitchen.

For a break from mezcal, stop for an evening coffee at Carajillo, a tiny shop specializing in brews made from beans harvested right here in Malinalco, even in owner Mauricio Zanco’s own backyard. It’s the perfect place for an afternoon pour-over, made with impeccable care from delicately roasted beans, before continuing your mezcal tastings into the evening.

Where to Stay

Malinalco is crowded with options for overnight stays, from simple family-run posadas to elegant farmhouses rented out on Airbnb and on to holistic spas for the well-heeled urban hippies who flock here.

One of the first luxury properties to open in Malinalco some 15 years ago, Casa Limón, occupies an old house at the end of a quiet, cobbled street a few blocks south of the central plaza. Its dozen rooms are decorated in calming shades of white and cream and overlook a lush courtyard studded with lemon trees.

Most of the other luxury options in town are slightly farther out, nestled against the cliffs that flank the village’s eastern and western sides. Among these, Casa Alamillo probably features the most dramatic setting. If Casa Limón makes for a comfortable home base to explore the village and surrounding countryside, Casa Alamillo, with its spa, garden, café, and swimming pool just below the hills, is a difficult place to leave at all.

Where to Eat

On weekends, when visitors from the capital stream into the cobblestone streets, vendors from the surrounding countryside drape blue tarps between colonial facades to block the dazzling mountain sun from overheating piles of bottle-green avocados, pink-and-yellow Mexican plums with insides like astringent custard, and mountains of freshly baked bread.

The most atmospheric place to eat at any time of day is right in the plaza. For breakfast, pick up a pan dulce from the stalls clustered around the plaza’s southeastern corner and get fresh juice from the stand just down the street (the only one in the market). For lunch, visit Doña Cristina for tacos de cecina, a salted beef that’s a specialty in this part of Mexico State.

Or stop by any of the elderly folks seated stoically behind clay griddles called comales as they shape thick, ovular tlacoyos out of blue-corn masa and fillings of fava beans or fresh cheese. Finish with a cup of sorbet, or nieve, from Don Mario at the plaza’s northeastern corner; they come in such flavors as guava, coconut, and nanche, a sour, yellow fruit that grows abundantly in the countryside.

The most famous culinary destination in Malinalco is the long row of open-air restaurants a short drive from the plaza at the southern end of town, an area known locally as Las Truchas, or the Trout. The dozens of restaurants here all serve variations on the same dishes: fresh fish taken from nearby ponds (you can fish for them yourself if you like), deep-fried or steamed in packets of foil with chiles, a fragrant local green called epazote, and onions.

Pick up whatever fresh vegetable seems most appealing at the market—golden ears of corn, pumpkin blossoms like bundles of tang-colored crepe, cobalt-blue wild mushrooms—and take them with you to local institution El Escarabajo or to Truchas Los Comales, run for the last 35 years by 75-year-old Doña Elena and and still overseen by her and two daughters.

But the city’s cooking has long extended beyond traditional options. Los Placeres opened 15 years ago in an old house right on the central plaza, complete with a patio offering sweeping views of the mountains. It’s the village’s classic destination for fine dining. Lunch or dinner might begin with quesadillas made from locally produced cheese and sweet-sour dried hibiscus and continue with fritters of huazontles (a pre-Hispanic grain, similar to amaranth but eaten fresh, as a vegetable) bathed in a brick-red salsa made from bittersweet pasilla chile.

Five years ago, Fatima Márquez and her husband Juan Pablo Quezada Aranda visited Malinalco from Mexico City for the first time. That weekend, they found a home to rent and space to open a café they called La Casa de Valentina. Today, it’s a full-scale restaurant serving coffee and pastries and traditional Mexican breakfasts in the morning, followed by an eclectic menu of sandwiches, salads, and pastas throughout the day, all made with locally sourced ingredients. As relaxed and atmospheric as the village itself, it’s a favorite among locals, weekenders, and those living in happy, self-imposed exile from the capital.

The Can’t-Miss Day Trip

The road from Malinalco rises quickly from the warm, humid valley and winds past lush subtropical vegetation on its way to the hilltop, mezcal-producing villages of Palmar and Zapote, shaded by towering forests of cedar and pine.

Along the way, narrow, rocky drives lead to the simple sheds where local families roast agave hearts in underground ovens for days at a time, crush the roasted plant into a sweet, smoky mash with heavy wooden mallets, and distill the fermented pulp in copper stills, as they have for generations. Maliemociones, a tour company run by local guide Adolfo Nava, organizes half-day trips to visit producers who offer tastes of agave spirit hot from their stills.

In such regions as Tequila and the central valleys of Oaxaca, agave distillates have grown over the years (in the case of Tequila, over a century) into an industry, a transformation reflected in the long rows of slow-growing agaves that bend like tidy vineyards over the flanks of hills. In Malinalco, the blue-green spikes of agave grow haphazardly among corn and beans, part of a traditional crop system that keeps the earth fertile and provides a diversified, if modest, income.

The DOC, of course, will not solve every problem mezcal producers here face. The certification process is lengthy and expensive, and the growing demand for mezcal has precipitated a severe scarcity in agave that has, in turn, led to rising prices in the primary material needed to produce the spirit. Yet, for some of the producing families here, the recognition of their skill and tradition has generated a new level of pride in their work. Nava says he’s noticed a significant increase in interest in local mezcals from visitors since September.

Like their counterparts in other small, mezcal-producing villages, many of the mezcaleros around Malinalco produce only sporadically, so it’s best to check ahead of time to be sure that someone will be around to receive you. (If not, Nava and his team specialize in hiking and canyoning, a more active way to experience the surrounding countryside.) Whatever part of the process you get to see, there’s still nothing like drinking mezcal with the people who made it, on the land that produced it.

Talk to anyone here, locals and transplants alike, and they’ll tell you in matter-of-fact fashion about the special energy that radiates from this place, like heat waves off summer asphalt. They’ll laugh, slightly embarrassed, when they fall into using such words as mystical in attempting to describe it. You won’t need more than a few minutes here to understand what they mean.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Gaddy at jgaddy@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.