Don't Read This If You're Bullish About Lyft

Don't Read This If You're Bullish About Lyft

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- The coming initial public offerings from Lyft Inc. and Uber give the public its first deep look inside the economics of car rides on demand. There were two obscure data points about Lyft that I found discouraging about the financial viability of that company, and potentially the entire industry.

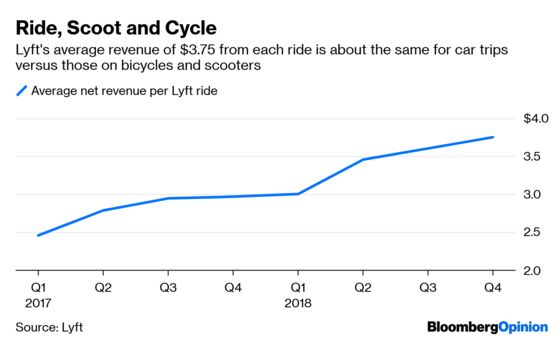

First, Lyft disclosed in its IPO document that it generates about the same average revenue for each car ride as it does from a trip on Lyft's growing network of rented bicycles and scooters: $3.75, to be exact, as of the fourth quarter. And second, Lyft's financials show that its average expense for each ride has gone up.

The financial dynamics and spending needs of the on-demand transportation industry remain in flux, but these two Lyft metrics aren’t reassuring.

People don't pay much to rent a scooter for a mile or two, but remember the important difference compared to a car: There's no driver in the equation when Lyft rents a scooter or bike, so the company keeps almost 100 percent of the fare. With a car ride, the driver effectively ends up with the vast majority of that money.

That might be good news for Lyft's economics from scooter and bike rentals. Maybe. But for the car business, think about all the money and effort Lyft puts into marketing to land new recruits, tuning algorithms to better match supply and demand, staffing driver support and operations centers, paying lawyers to deal with legal disputes and setting up car leasing programs.

For all that, the company ends up with about the same amount of money as when a user forks over $4 to rent a scooter for 15 minutes, which requires far less of the company's resources. I found the scope of the effort relative to the per-ride revenue disheartening, at least for the near-term financial prospects of Lyft's rides business.

The disclosure about Lyft’s revenue from cars versus scooters and bikes also wasn't in the draft version of Lyft’s IPO document. That suggests that Lyft may have included the figure because the Securities and Exchange Commission asked about it.

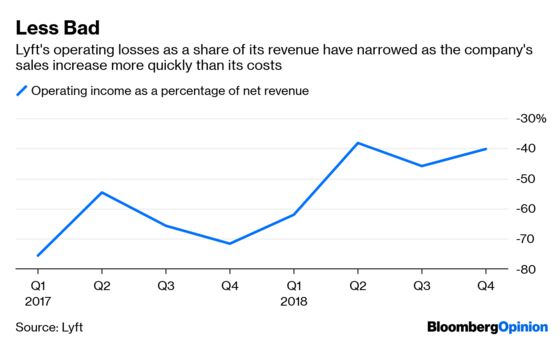

That's on the revenue side. On the cost side of the equation, the narrative is different depending on how you look at Lyft's spending efficiency.

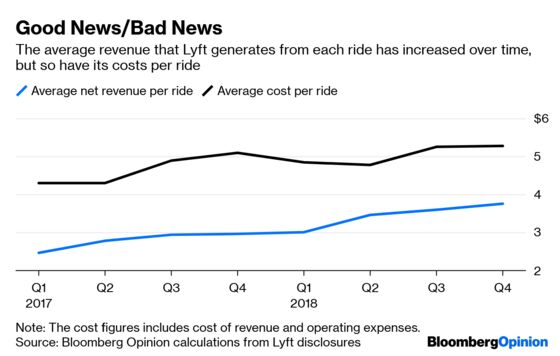

As a share of its revenue, Lyft's costs have come down and the company's losses have narrowed, although they're still high. I also looked at what the company is spending for each product it sells, which is a ride. On that basis, Lyft's expenses are getting worse.

Lyft doesn't break out costs in quite this way, but it discloses enough to calculate this: At the beginning of 2017, the company spent $4.31 per ride on insurance, processing credit-card payments, customer support staff, investments in driverless cars, advertising and other expenses.

Fast forward to the fourth quarter of 2018, and the cost per ride had increased to an average of $5.27. For full years, the average cost for each ride declined from 2016 to 2017, but rose last year.

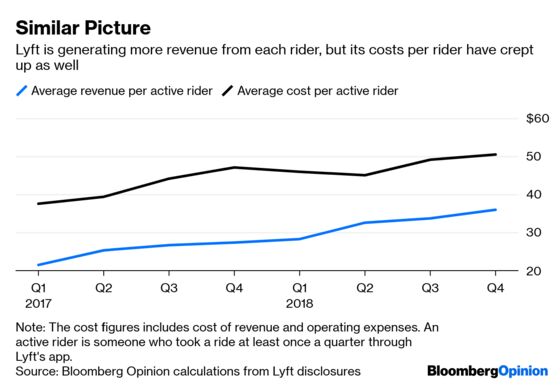

The picture is similar for the average cost for each active rider, which Lyft defines as someone who took at least one trip facilitated through its app in a given quarter. Lyft in its financial filing said it aims to increase the revenue it generates from each active rider, but the company didn’t say whether it looks at the flip side – the average cost per rider.

To Lyft's credit, its revenue per ride and rider climbed much faster than the average cost on the same basis. And the company has been investing in future projects such as autonomous cars, which push up expenses.

But even Lyft's basic cost of revenue, which excludes driverless technology investments, has increased since the beginning of 2017 on a per-ride and rider basis. As Erik Gordon, a professor at the University of Michigan Ross School of Business, said to me, if Lyft's costs per ride didn't improve from 2017 to 2018 – when the company's revenue more than doubled – when can investors expect those costs to come down?

None of this may matter to potential IPO investors. The company has devoted itself to growing fast, and it has. That's what new stock buyers seem to want. The company’s losses are getting less ugly. And it's good that investors are willing to roll the dice on fresh approaches to transportation and other fields that could use new ways of thinking.

Still, Lyft and Uber Technologies Inc. are aiming for large valuations, so investors should look every which way at revenue and cost economics, and ask the companies when these numbers will materially improve. If the answer is when driverless cars happen, that's a long time to wait for a viable business.

A version of this column originally appeared in Bloomberg’s Fully Charged technology newsletter. You can sign up here.

You can find the details by thumbing through topage 80 of the IPO filing. Thereyou’ll discover the disclosure that there's currently "no material difference" between the revenue per ride from cars versus bicycles and scooters.

A counterpoint: Maybe Lyft's revenue doubled because it also spent more.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shira Ovide is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering technology. She previously was a reporter for the Wall Street Journal.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.