London Defined Boris Johnson. Then Brexit Changed the Metrics

London Defined Boris Johnson. Then Brexit Changed the Metrics

(Bloomberg) -- After winning a second term as London’s mayor in May 2012, an ebullient Boris Johnson promised to devote his time “fighting for a good deal” for the U.K. capital.

Yet less than a decade later the city that made the British prime minister’s political career risks becoming an economic casualty of his premiership.

There’s a danger that London turns into collateral damage from the mantra to focus on the provincial regions that backed leaving the European Union and cemented the Conservative Party’s power. Business leaders in London warn the government needs more urgency in its efforts to boost the engine of U.K. growth in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

“If London’s economy does not get back firing on all cylinders, that will have all kinds of consequences, including for government revenue and its ability to run its leveling up agenda,” said John Dickie, chief executive officer of London First, a business lobby group. “Central London has been dramatically leveled down over the past 18 months.”

A cocktail of factors are weighing on London. They include the greater ability of its office workers to work from home, and reliance on international tourism that’s been curtailed by Covid-19 and regular changes to the U.K.’s travel rules. The City financial services district is still at the mercy of haggling with the European Union after Johnson largely neglected the industry in Brexit negotiations.

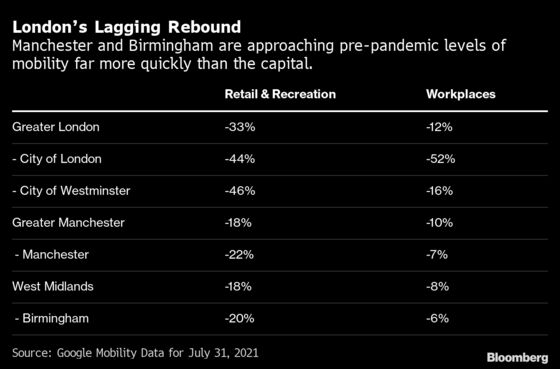

Google Mobility data puts London’s struggles in stark relief. While office attendance in cities like Manchester and Birmingham is approaching pre-pandemic levels, it’s still less than half what it was in the capital. London also has the greatest proportion of furloughed workers in England, and its lowest vaccination rate, in part because of its relatively younger population.

Businesses are calling on ministers to respond. Jace Tyrrell, CEO of New West End Company, wants ministers to reform business taxes, relax visa rules and entry requirements for travelers from the Middle East and Far East, and lengthen Sunday trading hours.

He’s concerned the government is complacent about London’s ability to return to full economic power. Footfall in the West End shopping and entertainment district was down 50% on pre-virus levels in the week beginning July 26, according to the New West End Company.

“Of course it will bounce back,” said Tyrrell, whose group represents 600 businesses in London’s shopping and entertainment district. “The challenge is whether it’s going to take two years, five years or 10 years. The quicker London recovers, the sooner Treasury can start restoring its balance sheet. That’s what’s being missed at the moment.”

The city of 9 million people helped make Johnson’s political career, and London seemingly had little to worry about in 2012. It hosted the Olympics that summer, showcasing its status as a global metropolis with Johnson as its cheerleader. The advent of the word Brexit that year was barely noticed with Greece in crisis, let alone on its way to becoming a reality.

Yet the government’s actions post Brexit have nurtured the perception London isn’t a priority. Since coming to power, Johnson has moved civil service jobs to parts of northern England where he made electoral advances in 2019.

Last year, the government forced City Hall, run by the opposition Labour Party, to increase public transportation fares as a condition of bailout money for the network after the pandemic wiped out revenue.

For Richard Burge, CEO of the London Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the quarrel over funding suggested the government sees the capital “as a political endeavor rather than an economic endeavor.”

The government said in a statement that it’s “fully aware” of the damage wrought on London by the pandemic, and is working closely with the municipality and transport chiefs to support the recovery. Businesses have received more than 3.5 billion pounds ($4.9 billion) in support, it said.

Minister for London Paul Scully said the government will help pay for the cost of Covid “but it won’t automatically pay for the choices of the mayor.” The point is that taxpayers in the north of England shouldn’t be subsidizing London commuters, he said.

The paradox is that London may not hold enough political capital for Johnson, yet it’s the dynamo to lead the recovery out of the pandemic that could be key to his future electoral fortunes.

He left office just weeks before the Brexit vote in 2016 as he spearheaded the campaign to leave the EU. After becoming prime minister three years later, his focus shifted to seats in Labour’s so-called “Red Wall” in northern England in the 2019 election.

Johnson himself sought to allay concerns about his “leveling up” plans in a speech last month. “It is vital to understand the difference between this project and leveling down,” he said. “We don’t think you can make the poor parts of the country richer by making the rich parts poorer.”

But the perception remains. The capital voted 60% to stay in the EU, and in the 2019 election, Labour won 49 of London’s 73 seats. Johnson’s Labour successor as mayor, Sadiq Khan, won a second term in May, beating his Conservative opponent by 55% to 45%.

“The Conservative government has pitted London against other parts of the country,” said Rushanara Ali, a Labour member of Parliament representing a London district. “They have built this narrative.”

Khan said in an emailed response to questions that the focus should be on getting people back into the city’s offices and other workplaces. On July 31, visits to cafes, shops, cinemas and attractions in the City were 44% below pre-pandemic levels, Google Mobility data show. Those to workplaces were 52% lower. Hotel occupancy in London was 31% in May, the lowest of any English region, based on the latest Visit Britain figures.

The problem for London is that there’s more political priority over, say, manufacturing jobs in the north than a far greater number in financial services, higher education or hospitality in the capital, said Jonathan Portes, professor of economics and public policy at King’s College London. The prime minister is neglecting London “both rhetorically and in practice,” he said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.