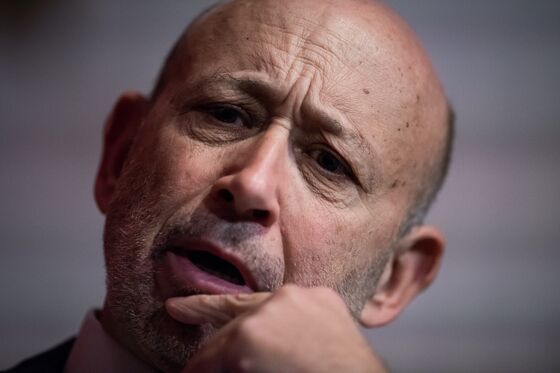

Blankfein's Final Days at Goldman Clouded by 1MDB Scandal

Goldman’s role raising about $6.5 billion for 1MDB has become one of its ugliest scandals in a generation.

(Bloomberg) -- When Lloyd Blankfein told his colleagues at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. in July that he was going to retire from the bank’s top job, he said the timing just felt right. When things are going wrong, he wrote them in a memo, you can’t up and leave.

Now in Blankfein’s final weeks as chairman of Wall Street’s most influential bank, things have gone wrong. Prosecutors are zeroing in on the firm’s work for a Malaysian investment fund that they say was raided in a historic plunder. Goldman’s role raising about $6.5 billion for 1MDB has become one of its ugliest scandals in a generation. In November, the U.S. Justice Department revealed that a former partner pleaded guilty to bribery charges, his deputy was arrested and the firm put a top Asia banking executive on leave. The stock is down more than 30 percent in 2018.

It’s enough to shock the firm’s well-connected former partners, who gathered in a hotel near the bank’s Manhattan headquarters Wednesday night for their annual dinner. Though the group tends to pooh-pooh popular criticism, many veterans are disturbed that the firm allegedly ignored or missed red flags and are annoyed by the hit to its image, according to interviews with 10 former partners, including members of the powerful management committee. To them, it’s the biggest threat to Goldman’s reputation since the firm’s post-crisis makeover.

“That is a terrifying thing,” said Michael Dubno, who was chief technology officer before he left in 2005 and is now an inventor. “We were more careful, more clean -- so whenever you see something like this it is very disturbing.”

‘Not Good’

Inside the Conrad hotel, former partners passed through an arched entrance that was an homage to the Pine Street building where Marcus Goldman opened an office almost 150 years ago. The dinner is a yearly tradition for the executives who made it to the top of the bank, pulling together one of the most elite groups in all of finance.

When Blankfein took the stage, he cracked up the audience with jokes about promotions, paychecks and retirement, according to two alumni. David Solomon, who took over as chief executive officer in October, addressed 1MDB by saying that one person can do a lot of damage. Goldman has portrayed Tim Leissner, who pleaded guilty, as a rogue employee.

According to bank spokesman Jake Siewert, Blankfein got a standing ovation at a lunch last week from fellow corporate executives including Bloomberg LP founder Michael Bloomberg. “That public affirmation from our long-standing clients,” Siewert said, “is more meaningful than backbiting and second-guessing from former employees.”

Blankfein, 64, led the firm through the financial crisis to the biggest profits in company history, and under him the stock outperformed most big-bank rivals. He spent much of the last decade cleaning up Goldman’s image after it paid a then-record $550 million fine in 2010 to settle claims it misled subprime investors. The billionaire led a three-year review of company standards, and Goldman dedicated hundreds of millions of dollars to philanthropic work for women and small businesses. When asked weeks ago what 1MDB means for Goldman, Blankfein deadpanned: “Well, it’s not good.”

Going Hollywood

The Wall Street powerhouse recently pivoted to Main Street, launching an online lending business called Marcus and an ad campaign to promote it. At the same time that Goldman is selling itself to consumers, 1MDB is mushrooming into the kind of heavyweight scandal that gets its own bestselling book and a Hollywood adaptation.

Last month was the worst for Goldman’s stock in more than six years. Malaysia’s finance minister has said he wants a full refund from the Wall Street bank, and the firm was sued by Abu Dhabi investment funds over their losses. Goldman made about $600 million working on 1MDB bond sales in 2012 and 2013, dwarfing what banks typically make from government deals. One of the biggest revelations in recent weeks is that the alleged mastermind, Jho Low, attended meetings with Blankfein.

“It doesn’t smell right, but I just don’t know,” said Dennis Suskind, who hired Blankfein at Goldman’s J. Aron & Co. unit and was a partner. “The thing about the firm is that they should have been monitoring it closer.”

Two other former top partners said the amount of money Goldman Sachs made from relatively plain bond deals should have been a bright warning to its highest executives. A third partner, who sat on the management committee, was struck that the firm was the only one competing for such a fat payday. Goldman has said some of what it earned from the deals was fair compensation for the risk it was taking.

Invisible Man

As Blankfein’s era ends, he hasn’t disappeared from the Wall Street scene. A press release showed him smiling this month as he used giant red scissors to cut a baby blue ribbon and open an education center named for his firm at New York’s LaGuardia Community College. On Monday, he helped lead a blockbuster $31 million fundraiser, where he celebrated with Solomon and former deputy Gary Cohn, who left to become President Donald Trump’s top economic adviser.

Not everyone who used to work for Goldman Sachs is shaken. Archie Parnell, a former managing director who was based in Hong Kong, said he was surprised but not panicking.

“The firm is a good firm,” said Parnell, who last month lost a race for a congressional seat in South Carolina. “The ship will be righted.”

Meanwhile, at this week’s dinner, Blankfein was greeted with more applause, a bank spokesman said. The event served as a sendoff, drawing a crowd that included longtime deputy Cohn and predecessor Hank Paulson. Harvey Schwartz, who lost this year’s race to run the bank, also showed.

The chairman shared his fears about life after Wall Street. He compared himself to the Invisible Man: When he takes off his Goldman Sachs wrapping, he said, there might be nothing underneath.

--With assistance from Steve Dickson.

To contact the reporters on this story: Max Abelson in New York at mabelson@bloomberg.net;Sridhar Natarajan in New York at snatarajan15@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Michael J. Moore at mmoore55@bloomberg.net, David Scheer

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.