Hyperinflation or Stagnation, Which Is Worse? Ask Latin America.

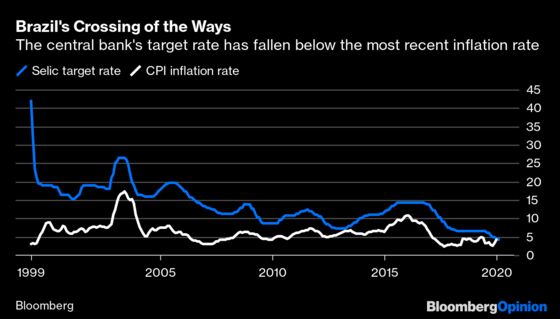

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- For Brazil, it should have been a momentous occasion. The country’s central bank cut its target overnight rate, known as the Selic, for the fifth time since July, and in doing so, sent the benchmark below the most recent rate of inflation. Effectively, Latin America’s largest economy now has negative real interest rates. It’s a startling development that speaks volumes about the region as a whole.

The move on Wednesday, easily missed amid the drama of world markets, neatly encapsulates how generations’ worth of assumptions about Latin America and its economic issues must now be thrown aside. For decades, the region’s problem has been inflation and the incipient risks of currency and debt crises. That pathology lives on in places, most painfully in Argentina and in the disaster that is the Venezuelan economy. But for much of the region, the fear of inflation and instability has been replaced by a fear of deflation and secular stagnation. It is a remarkable change.

Brazil, like many other countries in the region, suffered hyperinflation through much of the 1990s. Since it emerged from its last currency crisis in 1999, interest rates far above inflation have been the norm.

But there was no fanfare about the latest rate cut, as there is little to celebrate. The International Monetary Fund estimates that the region grew only 0.1% last year. Inflation is no longer a great worry, but the region exerts little control over its own destiny. Overseas factors have driven much of the decline. Brazil boomed in the years before the global financial crisis on the back of the high prices that the Chinese manufacturing complex was paying for its metals. Now that Chinese growth has slowed and begun to hit obstacles, metals prices have slumped into an eight-year bear market. That has choked off inflation, but has also stymied the growth that came with it.

There is also little joy about the victory over inflation and instability among finance ministries and central banks. For years, the joke at Mexico’s finance ministry was that they were the nation’s portero, or goalie. Like a goalkeeper in soccer, they could stop Mexico from conceding any goals, through the depressing cycles of inflation, currency devaluations and debt crises. And indeed, Mexico’s last home-grown crisis and default was as long ago as 1994. Years of controlling inflation, building local debt markets and bringing government deficits under control have sharply reduced any risk of another major financial crisis, even with a new left-wing populist president who scares many investors.

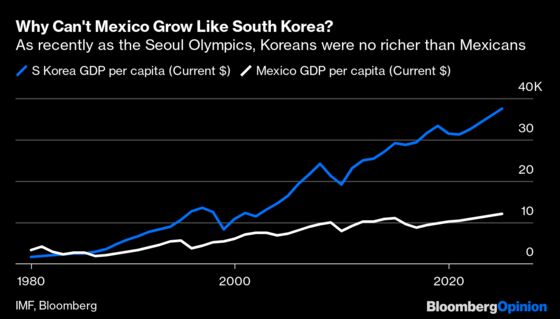

The problem is, these measures haven’t left Mexico with any way of stoking growth or expanding the economy. The finance ministry and central bank might between them give the country a good goalie. But there is no sign of the strikers needed to go out and score goals and help the country grow in the same way that Asian economies have been able to expand. For Mexico, the success of South Korea in particular is much-watched and envied, and the two countries’ diverging fates are telling.

It was Mexico that became the first emerging country to host the Olympics in 1968, at a time when it seemed about to join the club of developed nations. It took 20 years for South Korea to become the next developing nation to host the games, and it did so at a time when its GDP per capita had only just caught up with that of Mexico. The Koreans have suffered a major crisis more recently, in 1997-98. But they now enjoy triple the GDP per capita that Mexicans have. This puts Mexico’s success in imposing monetary and fiscal orthodoxy into a cruel perspective. It may have reduced the risk of a crash, but it seemingly can’t achieve much in the way of growth.

Even Latin America’s wealthiest country has seemingly reached the breaking point. Chile, which has benefited from impeccably orthodox economic policies ever since the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship, has found itself over-reliant on exports of metals. It has continued to grow, and even to reduce inequality, but at a painfully slow pace. Last year’s most shocking Latin American scenes came when Santiago went up in flames as people took to the streets, not because of some terrible default or devaluation crisis, but to protest a rise in subway fares. The country simply wasn’t growing fast enough to allow Chileans to save for an adequate retirement, or to afford a good education.

With even Chile retreating from macroeconomic orthodoxy, and stepping out on a politically perilous path to a referendum later this year that will decide on drawing up a new constitution, it’s become clear that Latin America has a new dilemma, as daunting in its own way as the previous one. To use the phrase coined by former U.S. treasury secretary Lawrence Summers, it appears to be in the grip of secular stagnation.

The region’s ultimate problem is that it isn’t investing enough in the things that might allow it to grow, such as improved infrastructure and education. Doing this will take time, and will require a build-up of savings by the population. But people are understandably impatient after decades of slow growth. In Mexico, in Brazil, and now even in Chile, leaders are under pressure to adopt populist remedies, and make transfer payments to address inequality. That makes it all the harder to find the funds to make the structural changes that might make their populations wealthier.

Meanwhile, the financial policy makers who have defeated instability and inflation have little that they can do. With negative real rates in Brazil and low rates in much of the rest of the continent, there is little scope for further monetary stimulus, while high debt levels leave little room for fiscal measures. Small wonder, then, that the victory over inflation, at one point inconceivable, has brought no cheering in its wake.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Beth Williams at bewilliams@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.