KKR's Noodle Snafu Shows Indonesia Is Still Risky Business

KKR's Noodle Snafu Shows Indonesia Can Still Be Risky Business

(Bloomberg) -- KKR & Co. has become the latest U.S. financial company to find out that doing business in Indonesia isn’t always straightforward.

The private equity giant is at the center of a tussle for control of PT Tiga Pilar Sejahtera Food, a Jakarta-based firm that makes instant noodles and distributes rice and seafood products. At a shareholder meeting in July, KKR -- which holds 35 percent of Tiga Pilar’s voting stock -- successfully voted to oust the company’s board of directors. The event ended with founder and President Joko Mogoginta publicly accusing KKR of attempting a “hostile takeover” as he stormed out of the gathering.

KKR, for its part, accuses Tiga Pilar’s management of shoddy corporate governance and questions its dealings with other companies linked to Mogoginta. Tiga Pilar will hold an extraordinary general meeting on Oct. 22 to try to resolve the dispute.

The rare display of public discord in the secretive world of private equity highlights the risks for foreign investors in a region co-founder Henry Kravis recently singled out as one of the most promising. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. are among Western financial firms that endured high-profile setbacks in Indonesia over the past two years.

“These cases often reflect what typically happens in emerging markets including Indonesia,” said John Teja, a director at Jakarta-based brokerage PT Ciptadana Sekuritas Asia. “Good corporate governance often becomes an issue in the country and the regulatory framework might not be as good as in developed nations.”

Rise and Fall

KKR first invested in Tiga Pilar in 2013, calling it a “great company” with “skilled management,” and at first, the bet looked like a winner. In 2016, Tiga Pilar posted record sales and profit as it launched a new food delivery concept and automated some sales processes. The stock jumped 61 percent that year.

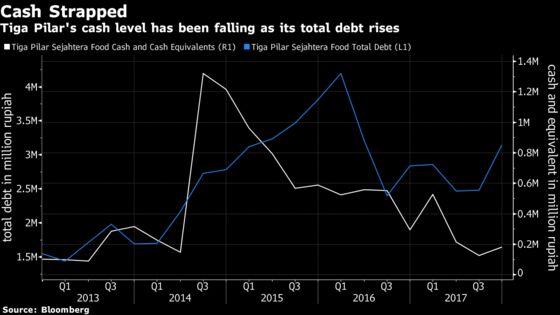

Then last year, Tiga Pilar’s fortunes turned abruptly. In July 2017, authorities raided one of its warehouses, alleging that the company had sold lower-quality rice as premium grain. The stock dropped 25 percent in one day and kept falling until it was suspended in July this year. Revenue tanked, pushing Tiga Pilar into its first annual loss. The company started running low on cash.

In December, a Tiga Pilar director flagged risks to its ability to refinance existing debt after bondholders rejected a plan to sell its rice unit to an affiliated company. Some eight months later, Tiga Pilar said it lacked the funds to make interest payments on some of its bonds. Its local-currency notes due 2021 were last quoted at around 82 percent of par, down from as high as 105.5 percent last November. Local credit rating agency Pefindo rates Tiga Pilar “selective default.”

Jaka Prasetya, the KKR Indonesia and Malaysia head who represents the buyout firm on Tiga Pilar’s board of commissioners, said it began asking questions early this year as Tiga Pilar’s financial woes came to light. Management wasn’t forthcoming with information, Prasetya, who is also a KKR partner, said in an interview.

Companies affiliated with Mogoginta account for 85 percent of Tiga Pilar’s 2 trillion rupiah ($131.6 million) of accounts receivable, according to Prasetya. Despite the company’s liquidity issues, it still managed to lend 200 billion rupiah to PT Jom Prawarsa, which is owned by Mogoginta, for an acquisition, Prasetya said.

“The number of affiliated or questionable transactions is just getting out of hand,” Prasetya said. “The only way to have a chance at saving the company is for proper new management to be put in place.”

Mogoginta didn’t respond to several requests for an interview. Efforts to reach Tiga Pilar for comment were unsuccessful.

While KKR scored a key victory in July at the AGM, Mogoginta’s side is fighting back. Interests associated the founder control about 5.3 percent of the company, according to exchange filings.

Goldman Dispute

Directors siding with Mogoginta in August filed a lawsuit against the board of commissioners, on which Prasetya sits, claiming no decision was made at the July AGM to replace the board of managers. They also argued that the current management remains authorized to run Tiga Pilar. Prasetya said he and other members of the board of commissioners have been barred by Mogoginta loyalists from entering Tiga Pilar’s offices.

Indonesia operates a two-tiered board system, under which the board of commissioners has a supervisory and advisory function and the board of directors are in charge of day-to-day management.

Speaking to reporters in Jakarta on Thursday, one of the commissioners, Hengky Koestanto, said it was hoped that the Oct. 22 meeting would appoint a new board of directors and allow for any new management to conduct an investigative audit of the company.

“The new board of directors will primarily focus on sorting out the debt problem, improving the relationship with suppliers, creating confidence among employees and improving the utilization of the factories,” Koestanto said.

While investors are drawn to Indonesia’s relatively young population of 260 million and economic growth that’s forecast to accelerate to 5.2 percent this year, pitfalls abound. Goldman Sachs last year said it was "surprised and disappointed" after a court ordered it to pay $24 million in damages to the founder of PT Hanson International for what was ruled to be an “illegal transaction” to buy shares in the developer. JPMorgan was only recently allowed to do business with government entities again following a one-year ban, the result of a bearish call on the country’s stock market.

Prasetya said he still believes Indonesia’s regulatory system will help KKR resolve the conflict. Yet he concedes the episode may impact KKR’s approach to investing in the country.

“We’re confident this one particular incident isn’t a representation of how difficult it is to do business in Indonesia,” he said. “Indonesia has a lot of opportunity for investment, but the bar for investing as a minority partner for us is going to be even higher following this saga.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Harry Suhartono in Jakarta at hsuhartono@bloomberg.net;Cathy Chan in Hong Kong at kchan14@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Thomas Kutty Abraham at tabraham4@bloomberg.net, Katrina Nicholas, Philip Lagerkranser

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.