Trump’s Goods-Sector Jobs Boom Was Great While It Lasted

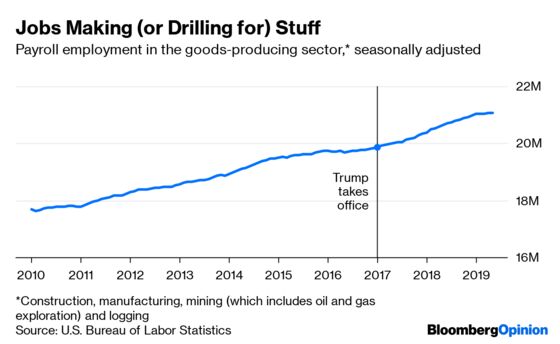

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- When Donald Trump was elected president in 2016, it was with a promise to, among other things, bring growth back to the non-urban, non-tech, non-college-degree-required parts of the economy. Whether President Trump was responsible (more on that later), this is exactly what happened during his first two years in office. Employment growth in the goods-producing sectors — construction, manufacturing and mining — which had flagged in 2015 and 2016, came back strong in 2017 and 2018.

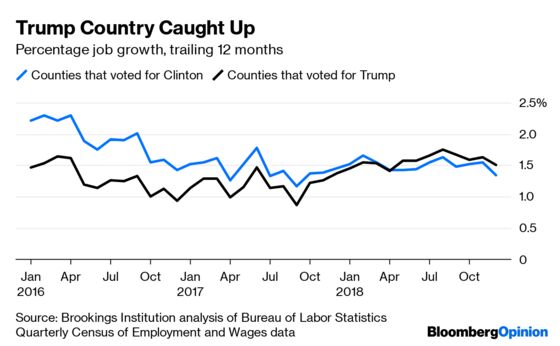

Because goods-producing industries tend to play a bigger economic role in the kinds of places that voted for Trump in 2016 than in the more urban areas that favored Hillary Clinton, this economic uptick has also played out geographically. Before the election, the rate of job growth in the counties that voted for Trump in 2016 lagged way behind that of the Clinton-voting counties. Since then, as this analysis of county data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages by the Brookings Institution’s Mark Muro and Jacob Whiton shows, the Trump counties have caught up with and passed the Clinton ones:

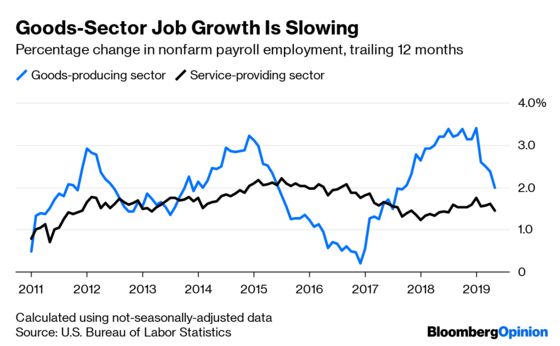

The county data are only available through the end of last year, and one can detect a slowdown since December in the more timely national numbers in the first chart. The jobs report released Friday showed that on a seasonally adjusted basis, the goods-producing sector still added jobs in May, but only 8,000 of them, a 0.04% increase over April. The much-larger service-providing sector added 67,000 jobs, a 0.05% increase. On a 12-month basis, jobs growth in the goods sector is still outpacing that in the services sector, but the slowdown is quite apparent.

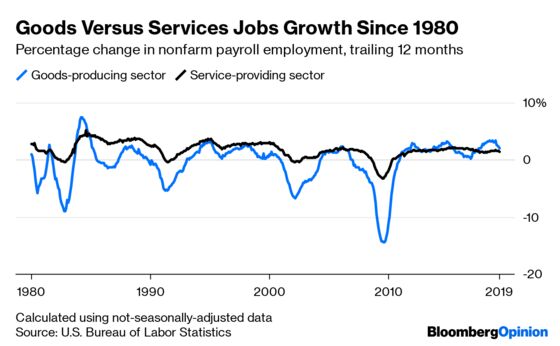

Before I go on, it is worth emphasizing just how remarkable the past two years have been. The national media has been full of articles questioning why some sector of Trump’s base still supports him despite some administration action (involving tariffs, usually) seen as likely to do them harm. But really, who are these people supposed to believe, the Washington Post or the “now hiring” sign at the factory down the road? There hasn’t been a period of goods-sector jobs growth (or goods-versus-services outperformance) like this since 1983-1984, and that was a short-lived post-recession bounceback, while this came almost eight years into an economic expansion.

What caused the Great Goods-Sector Jobs Boom of 2017-2018? What’s causing the slowdown? One cannot know for sure at this point, but I have some ideas. I also enlisted the help of a couple of experts: Martha Gimbel, director of economic research at the Indeed Hiring Lab, and Michael Hicks, an economics professor and director of the Center for Business and Economic Research at Ball State University in Indiana, the state with the most goods-sector-dependent economy. (Their input informed more than just the stuff I quote them on, but they shouldn’t be held responsible for anything but the quotes.)

Idea No. 1 comes from the above chart: Employment in the goods-producing sector shrank by 7.1 million, or nearly 29%, from July 2000 to February 2010. Job growth in goods has outpaced that in services for most of the current expansion in part because so many goods-producing jobs disappeared in the preceding decade. Once the economy began growing again, manufacturers, builders and the like were so short-staffed that they had to begin hiring. A related phenomenon was the 2015-2016 mini-recession, concentrated in oil and gas exploration and manufacturing, which created the preconditions for a bounce-back as well.

The fracking-enabled resurgence in domestic oil and gas production since 2008 has also created a lot of jobs over a longer period (although it has destroyed more than a few in coal mining). More recently, a 2017 uptick in economic growth overseas boosted demand for U.S. products, which affects goods producers more than it does service providers, as has the slowdown in global growth since the middle of 2018.

Then there are the policy changes made by the Trump administration and the Republican Congress. The most significant has been the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act that took effect at the beginning of 2018. It was accompanied by a relaxation of spending restraint by Congress, with the federal deficit going from 2.9% of gross domestic product in fiscal 2016 to a forecast 4.2% in fiscal 2019. The resulting stimulus has boosted the entire economy, but it probably boosted goods producers more. “The goods sector is more volatile than services,” Gimbel said. “It may be that it was just more responsive to the stimulus.” But as the stimulus fades (the deficit is expected to hold steady for the next couple of years), the goods sector is perhaps being more responsive to that, too.

The shift in regulatory posture that Trump’s election heralded also likely boosted the goods sector, although I have to think it’s the lack of new regulations and businesses’ anticipation of regulatory rollbacks more than the relatively limited actual deregulation that happened in 2017 and 2018 that did the trick. The regulatory shift may have affected goods more than services in part because the mining sector has been a focus of the administration’s deregulation efforts, but also just because decision-makers in goods-producing industries were more favorably inclined to Trump and thus greeted his election with more confidence and enthusiasm than their peers in services did: A 2015 survey of directors’ political affiliations found that industrial companies and energy/utility companies had the most strongly Republican-skewing boards. Then there’s Gimbel’s point about volatility: The goods sector is simply going to react more strongly to any policy change, whether positive or negative.

As for the president’s trade agenda, there surely are manufacturers that have boosted employment because newly imposed tariffs have granted them protection against foreign competition or led them to relocate to the U.S. production they previously did overseas. But tariff-related price increases and retaliatory tariffs from other countries are surely hurting some U.S. manufacturers as well, and it’s possible that tariffs and trade tensions are now dragging down goods-sector growth. They may be creating a few other jobs, though: According to Gimbel, postings on Indeed, a leading jobs site, show a marked increase since the beginning of this year in “jobs related to trade, such as trade analysts and compliance specialists.”

Finally, productivity growth in manufacturing has been excruciatingly slow over the course of this economic expansion. That’s been one cause of the goods-sector job gains — as demand increased, manufacturers had to hire more workers, because output per hour (the main measure of labor productivity) was flat. This is not a recipe for sustained, living-standards-increasing economic growth, though. One argument for the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act was that its big cuts in corporate tax rates would lead to productivity-boosting investment in equipment and technology. Evidence on that is mixed so far, but Hicks suggested in an email that, whatever the cause, a comeback in manufacturing productivity may be helping drive recent goods-sector job trends:

We saw productivity growth in 2018, but it slowed for manufacturing in the 1st quarter. That could be a statistical artifact of the late stage of a business cycle mixing with otherwise good productivity growth. If factory productivity is actually growing, but there was a quick slowdown in purchases of goods, then the output per worker would stall from the good path it was on in 2018.

So yay, maybe we’re seeing the long-awaited manufacturing-productivity-growth comeback! Then again, if it coincides with declining demand amid an overall economic slowdown, Hicks writes, “We should expect the beginning of declining employment, of which the past few months are just a hint.” After an impeccably timed goods-sector job boom, then, Trump may be about to experience a terribly timed slump.

On a more positive note, it could be that the great shift in jobs and economic activity from the goods-producing sector to the service-providing sector is at least going to be slower going forward. The goods sector’s share of nonfarm payroll employment peaked above 44% during World War II and stayed above 30% until the mid-1970s. For almost a decade, it’s been holding steady at or just below 14%, the longest such period of stability on record.

Including interest-rate changes! I tend to pay too little attention to the Federal Reserve because the world in general pays too much, but yes, the Fed overdoing monetary tightening in 2018 may have played a role in bringing on the goods-sector slowdown, although it's a little hard to say how exactly it might have sparked the goods-sector jobs boom.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.