Jes Staley Stakes Barclays’s Future on Investment Banking

Jes Staley Stakes Barclays’s Future on Investment Banking

(Bloomberg Markets) -- Jes Staley, the chief executive officer of Barclays Plc, is sitting in a conference room high above London’s Canary Wharf on an August afternoon. The conversation turns to risk. The Turkish lira is melting down, Brexit threatens to destabilize the British economy, and the world is bracing for any number of shocks, including European populism and a U.S.-China trade war. Reaching for his wallet, Staley says he isn’t too worried about those threats. He plucks out his Barclays credit card and holds it up: “This card is the biggest risk in the bank.”

Not every banker would say consumer debt is more dangerous than the risks a company such as Barclays faces in the capital markets. But then Staley is a true believer in the value of investment banking. Now he’s making his case that for all the drama at the lender in recent years—and there’s been plenty—there’s no better moment to make Barclays a global force in investment banking on a par with Goldman Sachs Group, Morgan Stanley, and his former company, JPMorgan Chase. Barclays is well-capitalized, it just notched two strong quarters of growth, and it recently settled legal entanglements that had long rattled investors. Taking on the U.S. giants means hiring more bankers, traders, and support personnel, winning more share in high-risk markets such as leveraged corporate loans, and doing it all without deploying more capital to the investment bank. “It’s time to let the bank run,” he says.

Or is it? Edward Bramson, a shareholder activist whose hedge fund holds a 5.4 percent stake in Barclays, appears to be among the skeptics who say the company’s true value doesn’t come from mastering the capital markets but from its more prosaic consumer-banking and credit card businesses. In a letter to his clients at Sherborne Investors Management LP in August, Bramson suggested that members of Barclays’s board might be receptive to a change in strategy that could “materially enhance shareholder value as well as the company’s long-term ability to be competitive.”

Staley dismisses Bramson’s missive as “cute.”

“I think the letter had very little impact, if any,” he says. “Not a single shareholder called us, and the board is 100 percent supportive of the strategy.”

Still, Staley’s embrace of investment banking runs counter to the retrenchment many of Barclays’s European rivals have undergone since the 2008 crash. In the aftermath, a raft of capital restrictions and leverage limits has sapped revenue and forced institutions to make hard decisions about where to employ their capital—and what kind of banks they wanted to be.

Barclays, a 328-year-old fixture in British life with Quaker roots, came to epitomize the excesses that preceded the crisis. Headlines decried the bank’s lavish bonuses, the reckless and at times unlawful action on its trading floors, and ultimately its arrogance. The wrongdoing, including its part in the industrywide rigging of the benchmark London interbank offered rate, cost the bank £16.5 billion ($21.7 billion) in penalties and bludgeoned its reputation. Over the past five years, its stock has trailed those of HSBC Holdings, BNP Paribas, and other competitors. As of late September, with a market value of £30 billion, it’s worth less than Lloyds Banking Group Plc, the domestic lender that was bailed out and, until 2017, partially nationalized.

The success or failure of Staley’s unorthodox move not only will determine the fate of a systemically important institution with £1.1 trillion in total assets, but it also will demonstrate whether he can buck the conventional wisdom and turn Barclays into the type of transatlantic powerhouse that existed before the crash changed everything.

Staley is pressing ahead even as the U.K. tumbles toward its divorce from the European Union on March 29. Brexit is bound to affect the value of the pound, London’s role as the hub for securities trading, and maybe even the credit quality of British borrowers if the breakup shoves the country into a recession. Staley supports the beleaguered proposal Prime Minister Theresa May put forward in the summer, one that would keep the U.K. in a customs union with the EU. Nonetheless, he says the uncertainty around Brexit is a big reason Barclays’s stock price is down 14 percent this year. “Why would you buy it before the Brexit resolution?” he says.

If that isn’t enough, there’s still unfinished litigation that predates his arrival at Barclays in December 2015. A U.K. court may reinstate criminal charges against the bank for allegedly misrepresenting the terms of a £12 billion fundraising from Middle Eastern investors in 2008. Meanwhile, a London-based private equity company, PCP Capital Holdings LLP, has accused Barclays of fraud in a £1.5 billion lawsuit linked to the same transactions. The bank denies the allegations in both cases.

Staley, looking relaxed after a Mediterranean holiday aboard his 90-foot yawl, says retreating from his plan is out of the question. From his perch on the 31st floor of Barclays’s blue-tinted glass building in London’s banking citadel, he can see the giant logos of HSBC, Citigroup, JPMorgan, and other rivals on the neighboring towers. A native New Englander with a Yankee’s knack for going his own way, he has the chance to leave his mark on a venerable British financial institution. “He’s been a contrarian his entire career,” says Glenn Dubin, a New York billionaire and co-founder of Highbridge Capital Management LLC, a hedge fund JPMorgan acquired in 2004.

Staley, 61, spent 33 years at JPMorgan, working in its São Paulo outpost during the hyperinflationary 1980s and eventually becoming the architect of its asset management franchise and CEO of its investment bank. Along with Steven Black, Bill Winters, and Charlie Scharf, he was part of the team led by CEO Jamie Dimon that forged what may be the most admired financial supermarket in the world.

A chatty, affable man with a habit of tapping the table when he talks, Staley is a throwback to a time when finance chieftains ran their domain with nerve and swagger. He eschews faddish banking lingo; there’s no talk of “customer journeys” or “digital payment ecosystems.” (Tellingly, he does like the term “bulge bracket,” connoting the Street’s top tier.) Far from being a remote presence tucked away in the corner office, he likes to roam the trading floor and drop by the building on the occasional Saturday to mingle with junior bankers putting in extra hours.

For all the backslapping, Staley is described by former colleagues as a demanding taskmaster who expects loyalty and efficacy from his people and won’t hesitate to jettison those who fall short. His impulsiveness has backfired at times, perhaps most notoriously when he sought to unmask a person who sent an anonymous letter to board members in 2017 criticizing the past conduct of a newly hired executive. Staley, who knew the banker from his JPMorgan days, was upset by what he deemed an unfair accusation. His actions triggered investigations of his own behavior. In May the U.K. Financial Conduct Authority fined Staley £642,000, and Barclays reduced his 2016 bonus by £500,000. Lawyers who handle whistleblower cases say he was lucky not to be fired.

Staley is repentant, sort of. “One of the things you need to learn as a CEO is that you have to check some instincts at the door,” he says. “But I believe in loyalty.”

Over the years he built a tight circle of colleagues, three of whom have followed him to Barclays and taken positions on its nine-member executive management committee. (With only one woman, Laura Padovani, the group chief compliance officer, the committee reflects a persistent imbalance in the upper echelons of finance.) If there’s one big idea that binds them together it’s that the one-stop-shopping emporium they helped develop at JPMorgan is replicable at Barclays no matter how much the rules of their industry have changed.

“I believe in universal banks,” Staley says. “I believe in having a diversified portfolio of consumer and wholesale businesses. I believe you’ve got to have the team to execute and deliver strong returns for your shareholders. And I believe in scale. What I don’t believe is this notion that only an American bank can be a bulge-bracket investment bank. That is flawed.”

In Bramson, Staley is facing a taciturn Brit who has a record of bending British financial-services companies to his will. In 2011, Bramson revamped F&C Asset Management Plc and delivered an 87 percent return for Sherborne’s investors. Barclays is his second-biggest-ever target, and so far he’s allocated more than £580 million of a £700 million fund to his campaign. In an Aug. 8 filing, Sherborne said it planned to engage with Barclays’s board on issues of “capital allocation, quality of earnings, capital adequacy, cost structure, and the search process for and mandate of a new chairman.” (John McFarlane, the chairman who led the hiring of Staley, is expected to step down in 2019.) Bramson declined to be interviewed for this article.

Staley has been comparing notes with his friend James Gorman on how to deal with Bramson. The Morgan Stanley CEO, who faced off with ValueAct Capital Management in 2016, reassured Staley that his strategy for Barclays’s investment bank is sound. But this showdown is just getting started. “Bramson has a strong argument to make,” says Ed Firth, an equity analyst at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods Inc. who has an underperform rating on the bank’s stock. “Barclays has some truly wonderful consumer businesses, but the problem is the big investment bank. It’s impossible to predict earnings in the division, which you’d accept if from time to time you made 20 to 25 percent return on equity. But we don’t even have that anymore.”

Barclays’s international consumer, credit card, and payments unit delivered a return on tangible equity of 21.2 percent in thefirst half, compared with the investment bank’s 11.1 percent. In a sign that investors have been putting their capital elsewhere, the company’s stock is trading at less than three-fifths of book value, a far cry from precrash levels that regularly exceeded two times book and well below the current average of 1.03 times for the 12 biggest banks in the U.S. and Europe.

Staley concedes that Barclays’s price-to-book ratio is woeful. “I don’t think any management team can sleep until their stock is over book value,” he says.

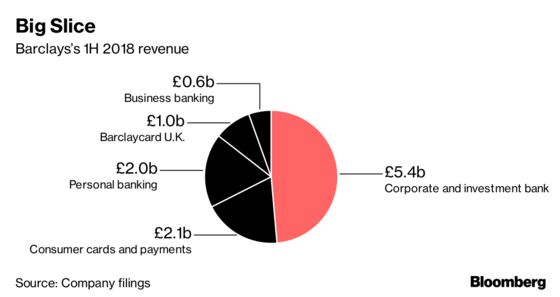

But he says there are indications his approach is producing results. Pretax profit in the corporate and investment bank jumped 17 percent, to £2 billion, in the first half from the same period a year earlier. Its capital markets arm handily outperformed those of its U.S. counterparts in the second quarter: Revenue from trading stocks surged 32 percent, to £601 million, more than double the average gains across the pond. Barclays’s mergers and acquisitions shop, meanwhile, has been winning lead roles in blockbuster deals, including advising and financing CVS Health Corp. on its $69.6 billion takeover of Aetna Inc., which is expected to close by yearend.

“Based on current results, you cannot say that this is a capital-hemorrhaging, loss-making business the bank should pull out of,” says Richard Buxton, CEO of Old Mutual Global Investors, a London-based asset management company and major shareholder in Barclays. “This business unit is performing.”

Reconciling the racy side of Barclays with its more staid retail arm has shaped the institution’s story for decades, says Philip Augar, author of The Bank That Lived a Little, a new book about the company. Nor is it the only European lender wrestling with existential questions. Deutsche Bank AG, for instance, is largely reversing its decades-long effort to be a transatlantic investment bank after a series of reorganizations failed to jump-start its sagging stock. Staley, the yachtsman-banker convinced this is a time to take market share from Deutsche and others, is tacking the other way. “If you’re a contrarian and you get it right, it’s a great tailwind,” he says. “And the contrarian bet here is the investment bank.”

When Staley came aboard, he found an organization that was demoralized and adrift. During the previous five years, the bank’s bosses had pulled their underlings in different directions. Under Bob Diamond, the brash American who built the capital markets business and bought part of the bankrupt Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. in 2008, the lender had elbowed its way into the great game of global investment banking. After Diamond left in 2012 amid the Libor scandal, the top job fell to Antony Jenkins, a reserved and intense Englishman who’d spent much of his career at Barclays’s retail arm.

Jenkins set out to cleanse the lender of its errant ways and yank it back toward consumer lending. He eliminated 7,000 jobs in the investment bank. He started winding down £90 billion in derivatives and other assets deemed noncore. He even erected Lucite tablets in the lobby of Barclays’s headquarters extolling the virtues of corporate responsibility. Yet the board balked at his push for another round of cuts, and in July 2015, the chairman, McFarlane, with the board’s support, abruptly fired him.

The aftermath left the atmosphere inside the executive suite toxic. Meetings among managers from the dueling divisions often broke down in fierce turf battles, say former senior executives. The bank felt directionless.

Sizing up the task before him, Staley knew he needed help. So on his first day he started reaching out to his old friends at JPMorgan. He called C.S. Venkatakrishnan, an MIT-trained Ph.D. who specialized in risk. He joined Barclays as group chief risk officer in March 2016.

Next, Staley brought in Paul Compton, a hard-charging Australian with unvarnished opinions, as chief operating officer. Compton, as chief administrative officer at JPMorgan, was steeped in the mechanics of banking infrastructure, including the labyrinthine information technology systems that control everything including settling derivatives trades and dispensing cash from ATMs.

Tim Throsby, JPMorgan’s global head of equities, came in to lead the corporate and investment bank. (Dimon, according to industry lore, was so miffed by the defections that he called McFarlane to complain.) Rounding out Staley’s squad was Tushar Morzaria, another JPMorgan alumnus, who’d been Barclays’s group finance director since 2013.

Even before Staley took charge, he and Morzaria holed up in a conference room and dissected Barclays’s strengths and weaknesses. In March 2016, Staley unveiled his plan to overhaul the bank. The company would reorganize into three divisions: Barclays UK, which encompassed the British retail bank and credit card arm; Barclays International, which held the corporate and investment bank, wealth management, and the U.S. and German credit card and payments businesses; and a new entity, Group Service Co., that would house and manage all the IT systems and infrastructure. Along the way, Staley had Jenkins’s tablets removed.

The changes were partly driven by the bank’s need to comply with U.K. regulators’ ring-fencing regime, which goes into effect on Jan. 1 and will require major lenders to separate their retail and investment banking arms. To help pay for the reorganization, Staley slashed the dividend to 3 pence per share from 6.5 pence. He also wanted to streamline the institution. So he decided to sell the bank’s 62.3 percent stake in Barclays Africa Group Ltd., a century-old business that Diamond had expanded in recent years.

Staley wasted little time before pushing into one of the more lucrative precincts of the capital markets—leveraged loans. These are loans that banks make to heavily indebted companies, often to finance acquisitions, before turning around and selling the debt to investors. They can be risky if lenders fail to offload them. When the crash came, banks were saddled with more than $200 billion in leveraged loans globally and suffered severe losses.

Now they’re back. In 2017 banks issued $494 billion of the loans in the U.S., the most in six years. Barclays structured more than $15 billion in debt in the first half of 2018, making it the No. 1 European bank in the leveraged loans space, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. In some deals, the bank makes loans to companies amounting to as much as 10 times a company’s earnings. The Bank of International Settlements, which is known as the central bank for central banks, said in a September report that the overall surge in leveraged loan volume, combined with looser lending standards, poses a risk to financial stability, especially in the U.S.

In the first half of the year, Barclays raked in $564 million in fees from leveraged loans, according to Dealogic, a financial markets platform. That’s the equivalent of a third of its total investment banking fees. Joseph McGrath, Barclays’s global head of corporate banking, says the market deepened the bank’s relationships with private equity players such as Blackstone Group LP and Apollo Global Management Holdings LLC, which use leveraged loans to finance deals. “It opens up other things for us and gives us incumbency with companies that we can eventually take public or sell at a future date,” he says.

Under a program begun in 2016, the bank phased out 13-year-old servers and data storage technology that Microsoft Corp. didn’t even support anymore. Compton, the COO, also started replacing outside tech consultants with full-time hires who, he says, cost 35 percent less and solve the problem of allowing your intellectual property to walk out the door every day. “That’s a very expensive way to develop technology,” he says. “And in this day and age, it’s also a very dangerous way to develop technology. Your ability to vet a consultant is not the same as an employee.”

More and more, Staley has pushed forward on digital fronts. In the U.S., Barry Rodrigues, CEO of cards and payments, is setting up a digital bank that will deploy an app and a payment card to compete with financial technology upstarts. To fend off cyberattacks, Staley greenlit the construction of security hubs in New Jersey, India, and the U.K. At the one in London, you have to pass through an airlock to gain entry. With about 50 cybersleuths patrolling the bank’s systems, the place looks like NASA’s mission control center.

As he approaches his third anniversary in the job—after all the rethinking, revamping, and restructuring—Staley says most of the heavy lifting is done. Barclays has wound down its noncore assets and increased its common equity tier-one ratio, a key measure of capital strength, to 13 percent in the second quarter from 11.4 percent in December 2015. On the cost-cutting front, the corporate and investment bank is still the most expensive part of Barclays, but its cost-to-income ratio fell to 66 percent in the first half of the year from 69 percent in the same period last year.

In March, Barclays settled the U.S. Department of Justice’s allegations that it caused billions of dollars in losses for investors by engaging in a fraudulent scheme to sell mortgage-backed securities from 2005 to 2007. The bank paid $2 billion in penalties. “At this time last year, we were being prosecuted by the U.S. government and the British,” Staley says. “It’s nice not to have that right now.”

For all this progress, Barclays’s shares have yet to show much life. Barrington Pitt Miller, a portfolio manager with Janus Henderson Group Plc, a Barclays’s stockholder, says the market may believe the bank has a structural problem that management can’t fix. Pitt Miller agrees with Staley that scaling up is more crucial than ever in investment banking. Yet it’s hard to see how Barclays can take on the U.S. banks by depending on organic growth and not investing more in the division. “The question is, can the bank deliver superior returns with the same capital?” Pitt Miller says. “Can you really do more with your clients with the same amount of capital at risk?”

What’s more, Staley’s whistleblowing scandal raises the issue of what happens to his JPMorgan allies if he errs again and has to leave. Would they follow him out the door? Bringing in a new management team would probably force the bank to make a strategic pivot and interrupt whatever progress it’s made.

Thanks to Bramson, one such pivot may be up for debate. Given the investor’s focus on capital allocation, some analysts speculate he may start with a proposal to further trim Barclays’s fixed income derivatives book. Joseph Dickerson, an analyst with Jefferies Group LLC, wonders if Bramson comprehends just how costly that would be. The bank already shed billions worth of these contracts as part of its asset wind down, and that resulted in £10.1 billion in losses. “I don’t think it would be feasible, from a value-creation standpoint, to shut down large swaths of the investment bank,” says Dickerson, who has a buy rating on the stock.

Girding for the tests to come, Staley pulls a page from a PowerPoint presentation and slides it across the conference table. It shows how quickly derivatives based on investment-grade, high-yield, and sovereign bonds are growing. The numbers are staggering—the notional value of interest-rate swaps alone is $319 trillion, up $30 trillion in only one year. Cutting further into this market wouldn’t just be impractical, it would be debilitating, he says. “If you want to be in the bond market, you have to be in the derivatives market because that’s how the buy side manages its risk,” he says. “And you can’t be in the capital markets unless you’re in the rates business.”

Staley says he’s quite comfortable with the risks of carrying £238 billion in derivatives liabilities on his balance sheet. Brandishing that credit card of his, he says the bank’s risk committee is far more focused on the £50 billion in unsecured consumer debt on its balance sheet, especially the lion’s share that’s in the U.K. If Brexit rattles the economy next year, many consumers may fall back on the plastic in their wallet to make ends meet, he says.

Although Barclays can do little about Brexit or the state of the markets, Staley is betting investors will see that the bank is finally “running free,” as he puts it. Still, two strong quarters don’t make a strategy. So the question now is just how long will stockholders give him to prove he’s right.

He points out that Morgan Stanley made $2.3 billion in net income in the second quarter, and Barclays made $1.6 billion, but the New York investment bank’s market capitalization is about $45 billion higher than that of Barclays’s. “That’s how far we’ve got to go,” Staley says. “It’s going to take a while.” Patience, unfortunately, is that rarest of things in the capital markets.

Robinson covers finance at Bloomberg in London. With Donal Griffin, Lisa Pham, and Stefania Spezzati

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Stryker McGuire at smcguire12@bloomberg.net

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.