Jersey City’s Renaissance Puts Mayor’s Ally in a Squeeze

Jersey City’s Renaissance Puts Mayor’s Ally in a Squeeze

(Bloomberg) -- Not long ago the skyline of Jersey City consisted of little more than abandoned warehouses, rotting piers and the Statue of Liberty. Now it sparkles with luxury residential high-rises and back-office towers of financial firms including Citigroup, Fidelity Investments and Goldman Sachs.

The city’s grit-to-glamour makeover has accelerated the last six years under Democratic Mayor Steve Fulop. Favoring tax incentives and less cumbersome regulation, he has been a boon for developers, including Mack-Cali, Lefrak, China Overseas America and Hartz Mountain, which have constructed tens of thousands of new living units.

But there could be a reckoning in New Jersey’s second-largest city, a federal investigation suggests. Some developers and builders have paid millions of dollars in all to a political operative and longtime ally of Fulop to expedite construction and permits through the city’s complex process. The tough-talking ally, Tom Bertoli, has been warned he could face criminal charges for failing to pay federal taxes on the payments.

A grand jury has been hearing evidence about Bertoli's dealings with developers, according to people with knowledge of the closed proceedings. Bertoli is being pressed by prosecutors to cooperate and has been asked for information about Fulop and other public officials in the state, two of the people said. The scope of the grand jury, whose existence hasn’t been previously reported, isn’t clear.

Several people familiar with the investigation said Bertoli’s woes could be politically embarrassing to the mayor. An examination by Bloomberg News of Fulop’s relationships with a handful of businesses turned up transactions -- one involving Bertoli -- that pose possible conflicts of interest. Those transactions include campaign donations and political arrangements; tax assessments; and personal home loans and an expansive oceanfront beach house that the mayor and his wife are building in Narragansett, Rhode Island, with an infinity pool on a third-floor deck.

Fulop hasn’t been accused of wrongdoing, nor have any of the developers. Through a spokeswoman, the mayor said that no special favors had been granted by or accepted from any campaign contributor or city contractor. The mayor is not privy to an alleged “federal investigation” into Bertoli, the spokeswoman said.

The inquiry may find that no one benefited improperly in Jersey City. Still, it suggests the pitfalls of any urban revitalization: businesses, including major developers with multibillion-dollar portfolios, have strong motivation to court local officials, whose arcane regulatory decisions can determine their projects’ success or failure. Those practices, even if they create potential conflicts for officials, rarely draw attention either because they are not specifically prohibited or because existing rules aren’t enforced.

In New Jersey, along with the grand jury's work, federal authorities have questioned several prominent developers and others associated with Bertoli in recent months, according to the people familiar with the investigation. The U.S. attorney’s office in Newark declined to comment.

The matter has even drawn in one of the state’s best known developers, Charles Kushner. He isn’t accused of wrongdoing but is standing by as a possible witness, according to people close to him. Kushner, sentenced to two years in prison for a political scandal more than a decade ago, is father to Jared, now an adviser to President Donald Trump and removed from the company’s day-to-day operations.

Kushner Cos. used Bertoli on its Trump Bay Street project in the city. It also gave tens of thousands of dollars a few years ago to Fulop’s exploratory campaign for governor. At the time, Kushner was trying to build another downtown office tower with tax abatements and city-backed bonds. The mayor promised the financial assistance but later did an about-face, irking Kushner.

Mayor and the ‘Janitor’

A veteran of the U.S. Marine Corps and Goldman Sachs, Fulop easily won re-election in 2017 on his pro-development credentials, which he boasted had made his city “the envy of New Jersey.” He declined to be interviewed for this article. “The mayor’s only consideration is what is best for Jersey City’s residents and taxpayers based on market and economic conditions,” his spokeswoman, Kimberly Wallace Scalcione, said in a written statement.

The political fixer at the center of the Jersey City investigation is so legendary for cleaning up messes that he is known locally as “the janitor.” Bertoli, a rough-hewn door installer and street organizer, comes from a storied political family in a part of the state whose bare-knuckle style inspired the film “On the Waterfront.” His father was implicated in a bribery scheme with a state senator in the 1980s and became a folk hero by refusing to become a cooperating witness.

When he met Fulop in 2004, Bertoli saw boundless potential in the Gulf War veteran with boyish looks and a smooth demeanor. Bertoli helped Fulop craft winning races for the city council and for mayor in 2013. Rather than join the administration, Bertoli focused on expanding his business as a permit expediter. His construction experience and reputation as a Fulop confidante was lucrative: Bertoli earned more than a half million dollars annually for several years, and he now faces possible federal tax-evasion charges for failing to file a return for the last 10 years, according to two people familiar with the inquiry.

In testimony as part of civil lawsuits against the city, some employees in Jersey City’s building and housing departments have claimed that Bertoli used his sway in the Fulop administration to punish people who refused to do Bertoli’s bidding. They describe him as a de facto construction coordinator hired by developers to get projects approved. They dared not get in his way.

Bertoli, 62, also declined to be interviewed for this article. In a 2015 deposition, he said developers weren’t paying for his political connections but for his construction expertise. Delays, he noted, could cost them tens of thousands of dollars a day. At Trump Bay Street, interest costs alone ran to $28,000 a day during construction, Bertoli testified.

He denied acting as a liaison to the Fulop administration on policy or personnel decisions: “If it doesn’t have to do with a hammer and a nail, I don’t work on it,” he said.

The lawsuits, by current and former city workers who say they were mistreated by the city, are continuing.

Wife’s Expanding Business

Fulop’s spokeswoman says he has had little interaction with Bertoli since being elected. Bertoli is one of more than a dozen expediters who work in real estate development in Jersey City, she said, and the mayor and Bertoli never discussed any of Bertoli’s clients.

Once in office, the mayor sought to parlay Jersey City’s turnaround into a run for governor. A super PAC, Coalition for Progress, was set up in 2015 and raised more than $3 million, much of it from the same developers who hired Bertoli. They include Mack-Cali Realty Corp., Ironstate Development Company and Dixon Advisory Services. The PAC’s president, Bari Mattes, a former finance director for U.S. Senator Cory Booker, has said that the fund’s purpose was to support multiple candidates. Fulop hosted some of the PAC events; donors and fundraisers said it was widely understood that he would be its prime beneficiary.

One of the biggest donations -- $250,000 -- came from Mack-Cali, a publicly traded real estate company with billions in holdings across the northeast and a substantial footprint in Jersey City. After Fulop became mayor in mid-2013, the company announced that its headquarters would move to its massive Harborside development on the Jersey City waterfront and revealed plans for other projects there, including a 69-story tower that was briefly New Jersey’s tallest residential building.

To navigate the regulatory process, Mack-Cali and its partners turned to Bertoli on at least two occasions, paying him more than $50,000 since 2013.

As a dominant landowner along the waterfront, Mack-Cali stood to benefit if the Fulop administration designated the area a special improvement district. With that, the city could impose a surcharge on the area’s 500 businesses and appoint a board to spend the money on maintenance, special events and infrastructure improvements.

Fulop himself began the process in April 2016, and it was championed by a city councilwoman. The Exchange Place Alliance SID won approval from the city council in 2017 along with a $3 million budget. Mack-Cali’s CEO, Michael DeMarco, became chairman of the district’s board.

Jaclyn Fulop, whose engagement to the mayor was publicly announced in December 2015, and who married him in July 2016, had a rental agreement with Mack-Cali during the time that the city was moving forward to establish the SID. The physical therapy practice she co-owns signed a lease in 2015 for a clinic at Port Imperial, a Mack-Cali property next to the ferry terminal in Weehawken, about five miles north of Jersey City, according to Fulop’s spokeswoman. By September 2018, the practice announced it had negotiated another lease deal with Mack-Cali and was relocating its Jersey City office to the Harborside complex, part of the special improvement district.

Jersey City’s ethics code forbids public officials or their family members from entering into financial ties that might create a conflict of interest. In December 2018, Fulop sought guidance from the Ethical Standards Board, corporate counsel and, to prevent any suggestion of a conflict of interest, outside independent counsel, according to Scalcione, his spokeswoman.

“To avoid even the appearance or perception of any conflict of interest, the mayor, in fact, has recused himself from any city negotiations or dealings with Mack-Cali requiring city approval,” Scalcione added, providing recusal letters that date back as far as June 2018.

DeMarco of Mack-Cali said his company negotiated the leases with Jaclyn Fulop’s business partner and didn’t realize the mayor’s wife was involved. He declined to say how much the company spent on a renovation of the space but said the deal was done at a market rate.

“She’s only a co-owner of the business,” DeMarco said in a recent interview, “so even if there had been some special deal, she would’ve only gotten half of it.” He said he consulted with Mack-Cali’s board and attorneys before approving the leases.

Jaclyn Fulop wasn't made available to comment, and her partner declined to comment. The mayor’s spokeswoman said Fulop never discussed the leasing deals with DeMarco and that there was no need for him to recuse himself in 2016 because the Fulops hadn’t been married when the lease was negotiated and signed. She added that the practice had an office in another section of Exchange Place before the mayor and his future wife had even met.

“Any suggestion that Ms. Fulop -- an independent, well-established and successful businesswoman -- would have any interest whatsoever in leveraging her husband’s position to run and grow the business she created smacks of rank sexism,” Scalcione said.

Tax Increases, Deferred

As the physical therapy business grew, the mayor and Jaclyn moved to a new home in Jersey City’s toniest neighborhood, the Heights. After the 2015 purchase, they started an overhaul of the three-story townhouse with the help of Bertoli and a business that benefits from Jersey City policies. Bertoli helped coordinate the early demolition plans, according to emails reviewed by Bloomberg, but wasn’t paid for the work.

The renovation was overseen by Dixon Advisory, the real estate arm of an Australian company with hundreds of millions of dollars in North American property. Its CEO, Alan Dixon, frequently socialized with the mayor and his wife. The company's United Masters Residential Property Fund had a small presence in Jersey City before Fulop became mayor and bought additional houses afterward. Dixon Advisory also gave $200,000 to the Coalition for Progress PAC before the Fulops’ project began.

Dixon Advisory benefited from one of Fulop's most controversial policy decisions. As mayor, Fulop can't set property tax rates but can block rate readjustments. Soon after taking office, the mayor canceled a tax revaluation that was meant to raise revenue and reduce disparities in the levies on homes.

Fulop said he was concerned that the process for selecting a reassessment company had been flawed and that longtime homeowners would face crippling tax hikes. Many people in residential neighborhoods complained that the mayor’s action left them subsidizing downtown development.

The matter went to court, where the judge accused the city of “intransigence” and forced it to proceed with the reassessment. “The city simply does not want a revaluation, period,” Hudson County Superior Court Judge Francis B. Schultz said in announcing his decision. Dixon Advisory was among those that benefited from the several-year delay.

Dixon Advisory pointed out that tax decisions were a matter for the independent Jersey City Tax Assessor’s Office, not Fulop or other elected officials, and that an outside vendor determined the valuations in the citywide reassessment.

Manhattan Skyline View

Dixon Advisory’s construction unit served as general contractor for the Fulops’ residential makeover, according to public records. Though unassuming from the street, the townhome has been transformed by a gut renovation and the addition of balconies on the back with views of the Manhattan skyline.

The Fulops agreed to pay Dixon Advisory $485,000, according to public documents, for a complete overhaul with new wiring and plumbing, high-end appliances and a rear expansion cantilevered on steel beams over a cliff. The basement floor was dug about two feet deeper and outfitted with a separate suite and a gourmet kitchen.

In 2016, once the work was completed, the Fulops refinanced the property with Bayonne Community Bank.

BCB, which has about $2 billion in assets and branches scattered across the state, had been approved to handle some Jersey City funds in 2013, before Fulop became mayor. Shortly after he took office, executives at BCB reached out to his administration to ask about opening more branches there, according to people close to the matter.

The Fulop administration welcomed the effort, and in 2015 the city's retirement commission transferred millions of dollars in pension funds to an account at the bank. Fulop, who sits on that commission, wasn't present for the vote approving the transfer, according to city documents.

Bayonne Community Bank didn't respond to requests for comment.

Fulop’s spokeswoman said that Dixon Advisory was chosen for the home renovation solely because of its reputation for quality work and that the mayor paid market prices. Dixon Advisory, she added, had no business with the city. A blog called Real Jersey City reported previously on Dixon Advisory’s role in the renovation.

Dixon Advisory “has completed market-priced work for the mayor of Jersey City, as well as many other clients, and has made market-level profits,” Alan Dixon, the CEO, said in a statement. “All due and proper process was followed one hundred percent of the time. We reject any suggestion to the contrary.”

Dixon Advisory customarily charges a 22.5% markup on renovation projects, according to its corporate filings in Australia. The company declined to comment on what it charged the Fulops.

The North American operation run by Alan Dixon has been dragging down the performance of its Australian parent. Shares of Evans Dixon Ltd., formed by Dixon Advisory’s merger with a wealth management company two years ago, closed at 79 cents on June 27, down from $2.50 last year. On June 12, Alan Dixon stepped down as CEO of the parent, while retaining his title at Dixon Advisory, to concentrate on the troubled U.S. Residential Fund.

Infinity Pool in Narragansett

Both Dixon Advisory and Bayonne Community Bank are involved with a separate vacation property the Fulops are building. In January 2018, the Fulops bought a wood-shingled oceanfront home for $820,000 in Jaclyn’s hometown of Narragansett, Rhode Island.

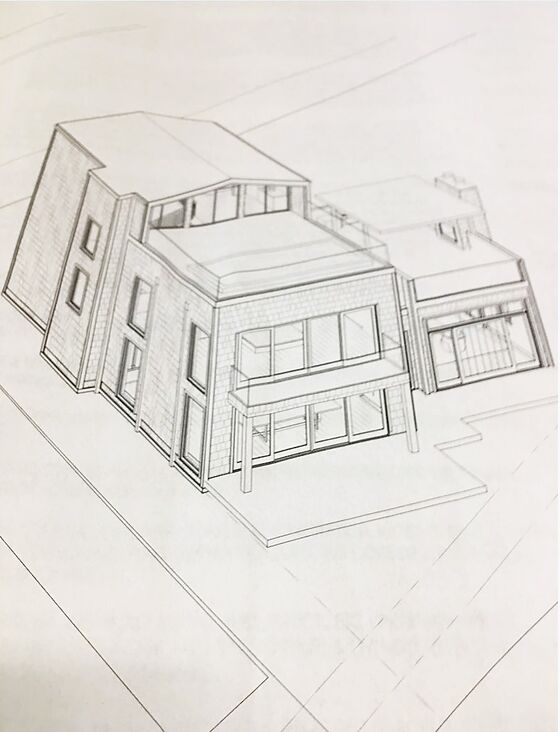

The couple razed the existing structure. On a recent visit, the framing was taking form for its replacement, a three-story beach house overlooking the Atlantic. The 3,000-square-foot home, with 1,400 square feet of terraces, was designed by Dixon Advisory’s architects. One of those architects testified at a zoning hearing, assuring Narragansett officials the house would be structurally sound and environmentally efficient.

Bayonne Community Bank, which refinanced the Fulops’ Jersey City home for $900,000 in 2016, extended a home equity line of credit of $650,000.

Both Fulop homes are listed as collateral, according to public records. Fulop said the mortgage in Jersey City was a 30-year loan with a fixed rate of 3.75%, which was in line with the market in 2016. The Fulops haven't tapped the credit line, according to the mayor's spokeswoman.

Documents on file in Rhode Island estimate the general contractor’s costs of labor and building supplies for the beach house to be $500,000. Fulop, through his spokeswoman, said that figure doesn’t include plumbing, mechanical and electrical expenses, and declined to give a total projected cost for the house.

Two local builders who specialize in high-end oceanfront property said the completed house the Fulops are planning would typically cost around $1.5 million, with features like the third-floor infinity pool contributing to the cost.

Matt Davitt, president of Davitt Design Build in West Kingston, R.I., said he had consulted last year with representatives of Dixon Advisory, which he said characterized itself as project manager and architect as well as the Fulops’ representative for the home.

Davitt said he reviewed the plans and estimated that it could cost a general contractor as much as $600,000 to $700,000 to frame the house, given the cost and complications of reinforcing the structural support of an elevated pool. Electrical, plumbing and mechanical costs would be an additional expense, he said.

The project's general contractor, Superior Construction Group of Middletown, R.I., manages high-end construction projects including vacation homes and resort properties. The Fulop home is its first project involving Dixon Advisory, according to Daniel Szymanski, a Superior Construction vice president.

Szymanski declined to say whether Superior Construction was being paid by Dixon Advisory, the Fulops or some other owners' representative. When asked how Superior could build the property for less than what other builders consider a market price, he said: “Maybe the other builders should hire me.”

Fulop’s dealings with Dixon Advisory and Bayonne Community Bank were fully proper, according to the mayor’s office. “To be clear, at no time has the mayor or his wife asked for or received any special considerations from any local business,” said Scalcione, his spokeswoman. The local contractor and Dixon Advisory charged fair market rates, she said, adding that Superior Construction “has no financial relationship with Dixon.”

Bertoli Vows to ‘Stand Tall’

Weysan Dun, a former special agent in charge of the FBI’s New Jersey office, said he wasn’t aware of the mayor’s finances or the latest inquiry but that appearances matter. “When you’re a public official, especially when you’re an elected official, people put their trust in you,” said Dun, who is now head of the Nebraska Crime Commission and a consultancy called Dun Global Solutions Group.

“So it is imperative that you avoid any kind of relationship or dealing where it may appear that you, a family member or a business that you may have a stake in could benefit from your actions," he said.

Bertoli, for his part, is resisting the pressure coming from federal agents, according to two people familiar with the case. He has told friends that, like his father, he’ll “stand tall” and face any charges rather than provide information to prosecutors.

Others stand more willing. Kushner Cos. is suing Fulop after the city withdrew the tax incentives it was promised in 2017. The Kushners say in court papers that they are being punished by the Democratic mayor for their politics, citing the family’s ties to the Republican president. The mayor said at the time that the Kushners had violated their agreement by changing development partners and missing deadlines.

Charles Kushner has made it known that he is eager to help with the investigation, according to people familiar with the case. He declined to comment for this article.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Winnie O'Kelley at wokelley@bloomberg.net, David S JoachimJeffrey Grocott

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.