No One Knows What to Do About Italy’s Deadly Bridges

No One Knows What to Do About Italy’s Deadly Bridges

(Bloomberg) -- Placido Migliorino has spent the last year on a mission to keep his fellow Italians out of danger.

The 60-year-old engineer’s job at the Transport Ministry is to roam the country checking highway bridges are as safe as their privately run operators say they are after the collapse of one in Genoa in August 2018 killed 43 people. He’s inspected more than 200, scaling the structures with special ladders and in lifts, and concluded that at least four ought to be closed or banned to heavy trucks.

But making that happen proved to be the hard part, involving a Kafkaesque journey exposing the bureaucracy, self-interest and political paralysis that’s left one of Europe’s largest countries facing a dangerous truth: infrastructure is crumbling, lives are at risk and no one knows what to do about it.

The companies managing the roads have the responsibility to ensure their bridges are safe as part of the concession contracts. The ministry has supervisory powers, so when they find something is remiss they can invite the companies to act, though can’t force them to do anything. That would involve appealing to the government’s representative in the province, known as the prefect.

In turn, these prefects say they can close roads for general public safety, but aren’t legally responsible if those roads are under concession. So often action is only taken after the judiciary has been called upon to intervene.

“The paradox is that the ministry doesn’t have the power to order traffic bans,” Migliorino, whom local papers have dubbed “the mastiff” for his zeal over the years, said in his office in Rome. “I can’t physically go and close the highway.”

The country is now focused on containing the coronavirus after Italy emerged as Europe’s epicenter, earmarking 7.5 billion euros ($8.4 billion) to counter the impact. Schools and universities were closed as the disease left more than 100 people dead, mainly in the north.

When it comes to the roads, a wobbly ruling coalition hasn’t moved beyond heated rhetoric.

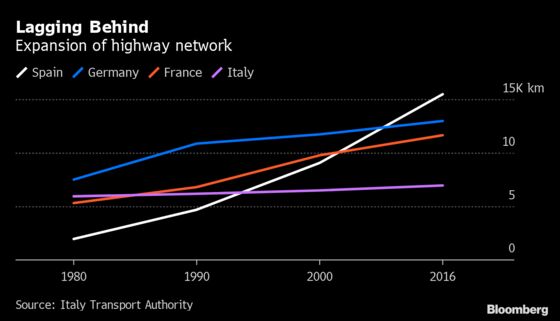

All but 1,000 kilometers of Italy’s 7,000 kilometers are run by private companies. The government debate has focused on revoking lucrative highway concessions, which would involve taking on one of Italy’s most powerful families: the Benettons, whose vast business empire includes Autostrade per l’Italia, Europe’s largest toll road operator.

There are about 2,000 highway bridges in Italy and many date back to the construction boom in the 1930s under dictator Benito Mussolini and the postwar recovery programs of the 1960s. The job of inspecting them got more urgent after the accident in Genoa when dozens of cars and trucks fell 100 meters from Morandi Bridge onto rail tracks and streets below.

The bridges that Migliorino has inspected so far are in central and northern Italy, and details of his requests were revealed in confidential court orders reviewed by Bloomberg.

The game of bureaucratic ping pong he found himself drawn into was particularly messy in the case of the Cerrano bridge that connects the south-east to the rest of the country, those documents show. Migliorino and Autostrade, which owns the concession to run it along with nearly half of Italy’s highways, confirmed the authenticity of the order.

Migliorino visited the viaduct, which soars 90 meters over rolling green hills in an area on the Adriatic coast prone to landslides, several times since September 2018. He found what he called “advanced deterioration” of some metal parts, and sent several letters to Autostrade.

In one, dated Nov. 29, he recommended a heavy truck ban, but says he was ignored. He wrote to the prefect who said the ministry and Autostrade needed to find a solution in a meeting the following month attended by all interested parties, according to confidential minutes of the meeting reviewed by Bloomberg. Representatives from Autostrade and the ministry—including Migliorino—as well as police officials and the president of the province were at the meeting.

It wasn’t until the prosecutor asked the judge on Dec. 18 to issue an order that the ban was finally implemented, the court document shows.

There were then at least four more meetings between ministry officials and Autostrade. It was agreed that the company would set up a monitoring and alert system to detect movement in the ground beneath the bridge so that traffic could be stopped in case of heightened risk.

At that point, the ministry gave the go-ahead to re-open the bridge to trucks. But the plan still needed to overcome another hurdle, and quickly: locals were driving back to their hometowns in the south after winter holidays, and nearby roads were jammed with heavy trucks as a result of the ban. Autostrade had to apply to the courts to have it lifted.

On Jan. 13, Autostrade said in a statement that the viaduct was safe, constantly monitored and not subject to any significant geological movement. The magistrates ruled that it could be reopened to trucks on Jan. 30, though one lane remains closed and there are other speed limitations.

The problem is that the state, provincial and regional authorities and private concessions are all reluctant to take responsibility, said Ercole Incalza, a senior official at the Transport Ministry from 2001 to 2014.

“There’s this passing of the buck,” he said. “It is in fact a kind of hallucinatory film because then it is the judiciary that intervenes. I think the guarantor, so the ministry, should be able to intervene first.”

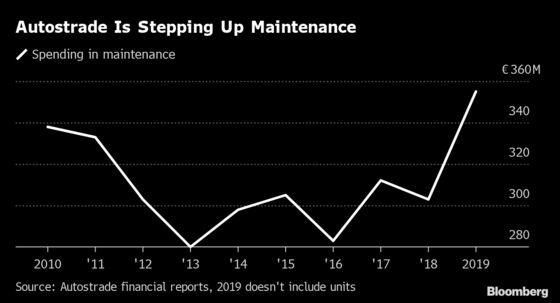

Highway operators have stepped up maintenance, restricting traffic at many bridges and tunnels since the Genoa tragedy. For its part, Autostrade has also pledged to almost triple investments on its network to 5.4 billion euros ($6 billion) and increase spending on maintenance work to 1.6 billion euros over the next four years. It changed chief executive officer and replaced an internal unit that carried out assessments with an external company.

“Dialog and a continuous exchange of information with the Transport Ministry is important to us, in addition to the thorough safety checks they carry out,” Autostrade said in a response to a request for comment. “In some cases it’s the company that requests technical feedback from the ministry, to find the best way to carry out work.”

Until June, none of the repairs Autostrade was carrying out had been classified as requiring immediate action, according to a table dated Sept. 14 posted on Autostrade’s website. By December, it said six viaducts had “elements” classified at the highest risk level. Five of them are around Genoa and all have traffic restrictions due to maintenance.

Campaigners like Augusto de Sanctis of Acqua Bene Comune say time is critical. His non-profit group, which was set up to urge local governments to keep water utilities in public hands, has since looked into infrastructure and has been lodging freedom of information requests with the authorities. The aim is to reveal where the most potentially dangerous bridges are located.

“We cannot wait for the judiciary to step in every time,” he said. “The information we ask for—about the state of roads, bridges and tunnels—should be at everyone’s disposal so that we can have an informed and serious public debate.”

The three other viaducts that Migliorino wanted closed or banned to trucks late last year were the Altare in Liguria, Bormida in Piedmont and Giustina in the south. The list is growing. This week, magistrates ordered the partial closure of three viaducts on the Naples to Canosa highway, prompted by Migliorino’s most recent controls.

Altare operator Autostrada dei Fiori declined to close the bridge, but immediately began to implement the requested safety improvements and is limiting traffic because of the maintenance work. Autostrada dei Fiori, part of ASTM, Italy’s second-biggest highway company, said by e-mail that their checks have shown the structure is safe. Traffic restrictions were also put in place at Autostrade’s Bormida and at Giustina.

Migliorino is now focused on bridges and tunnels in the Genoa region of Liguria, in the north.

While lauded as technical marvels, Italy’s highway bridges were often built in terrain best avoided, like along riverbeds and unstable slopes, and weren’t designed for the thousands of cars and trucks carrying heavy loads that cross them these days. During the 1960s construction boom, competition led to companies seeking cheaper materials.

Ensuring they’re safe got more complicated in the late 1990s when the government began pulling apart state-owned industry to reduce debt and meet the goals for joining Europe’s single currency, the euro. Many bridges, tunnels and highways passed to private control.

Today, Autostrade is the largest of 22 concessions. Owned by Atlantia SpA, whose main shareholder is the Benetton family, it manages some 3,000 kilometers (1,864 miles) of highway, including the viaduct that collapsed in Genoa.

Autostrade has always denied negligence in that tragedy. Afterward, the government said it wanted to start procedures to strip the company of its lucrative contracts, which would have included a break-up payment to the company at the time. For its part, Atlantia has signaled it’s ready to cut its stake in Autostrade to 50%, or below the current 88%, and that it’s open to public investment firms.

The six-month-old government in Rome is split between the Five Star Movement, which favors a revocation of the contracts, and the Democratic Party, which would be content with a revision of the Autostrade concession deal, cutting tolls and a boost in spending.

Following recent regional elections, the Democrats might have the upper hand. In the meantime, parliament confirmed a government decree that significantly reduces the penalties Italy would have to pay in case of revocation and also also prevents licensees from pulling out unilaterally.

Ministers also promised to set up a new agency to monitor safety and pledged to pour billions of euros into countering hydro-geological risks. All that materialized, though, was the collapse of another bridge.

This one, operated by Autostrada dei Fiori, fell during a mudslide caused by heavy rain in Liguria in November. Luckily no one was hurt. The bridge was rebuilt and reopened two weeks ago. The highway operator plans to revamp more than 150 bridges built in the 1950s before the end of its concession in 2036.

The highway operators claim Transport Ministry supervision is an issue. Fabrizio Palenzona, chairman of their association, said that when the ministry took on the responsibility for monitoring safety, checks became less effective as funds were diverted to fill budget gaps.

When asked for a response to that claim, a ministry spokesman didn’t respond. Transport Minister Paola De Micheli addressed the issue in an interview with Radio24 earlier this year, saying that while there had been some “obvious neglect,” the country must “attribute responsibility in order of importance, first to those who hold the concessions.”

Ministry officials, as well as several Autostrade executives, are under investigation for the Genoa collapse. Italy’s state auditor, the Court of Accounts, said in a December report that the ministry’s supervision is understaffed and underfunded and the way highway operators can be sanctioned needed to be reformed.

While private highway operators have been in the spotlight of late, state-run roads have also seen bridges collapse. Three since 2017 have killed a total of three people.

There are about 30,000 state-run bridges and tunnels on national roads in the country. The Italian provinces association carried out an initial health check on about 6,000 of them arguing that a third need urgent work. For about 1,000, it’s not even clear who’s responsible for the maintenance and supervision, said Oliviero Baccelli, professor of transportation politics and economics at Milan’s Bocconi University.

The government in 2019 set aside 11 billion euros over three years to counter high risks of landslide or floods across about a fifth of the country, but regions are only able to spend a fifth of the funds allocated due to red tape.

The confused approach to bridges raises deeper concerns about the state of other ageing infrastructure. In fact, the next big worry is highway tunnels. Autostrade is carrying out a safety check for its 587 tunnels following a partial collapse of a tunnel ceiling on a highway near Genoa on Dec. 30.

“Very little has been done,” said Egle Possetti, who leads a group representing the families who lost relatives in the Genoa tragedy. “We as a country have been obsessed about the revocation of Autostrade’s concession in the past few months, but we actually have to deal with 30 years of neglect—and that can’t be solved overnight.”

--With assistance from Hayley Warren, Daniele Lepido and Tommaso Ebhardt.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Caroline Alexander at calexander1@bloomberg.net, Rodney Jefferson

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.