Italy’s Banking Money Pit Gets Deeper After Draghi’s Sale Fails

Italy’s Banking Money Pit Gets Deeper After Orcel Shuns Draghi

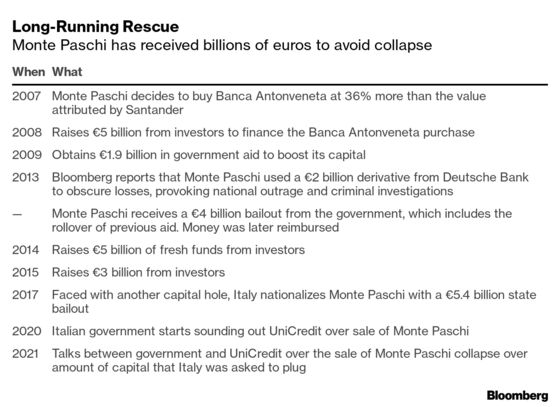

(Bloomberg) -- Banca Monte dei Paschi di Siena SpA has burned through about 18 billion euros ($21 billion) of taxpayer and investor cash since 2008, and there’s still no fix in sight.

Fears in Italy are growing that the world’s oldest bank will become an even deeper money pit for Prime Minister Mario Draghi’s administration after talks to sell the troubled lender to UniCredit SpA collapsed over the weekend.

Italian taxpayers are stuck with Monte Paschi for the foreseeable future, and revamping the bank -- founded in 1472 to help the Tuscan city-state of Siena recover from the plague -- could require another 7 billion euros, according to people familiar with the matter.

Italy has a history of dumping money into companies that can’t be allowed to fail for social and political reasons. State airline Alitalia cost taxpayers over 9 billion euros since 2008 before it was finally shut down to make way for a smaller state-owned successor. Italy also poured nearly 1 billion euros into ailing steel-plant Ilva to protect the Taranto region where it’s based.

“Monte Paschi is just the latest example of an Italian zombie firm,” Stefano Girola, a portfolio manager at Alicanto Capital SGR. “It doesn’t matter how many losses it’s piled up, how much capital has been wiped out and that uncertainty about viability is mounting, it will not fail because the state will keep it alive.”

Talks between the government and UniCredit fell apart after the two sides failed to agree on how much new capital Monte Paschi needed before the sale, according to people familiar with the matter. It’s a blow for Draghi and UniCredit Chief Executive Officer Andrea Orcel who spent months trying to find a solution.

Even after billions of euros of taxpayer funds, Orcel argued that about 7 billion euros more was needed to restore Monte Paschi’s capital buffers and permit a deal that wouldn’t hurt his bank’s reserves, but the government thought he was asking too much, said the people, who asked not to be identified.

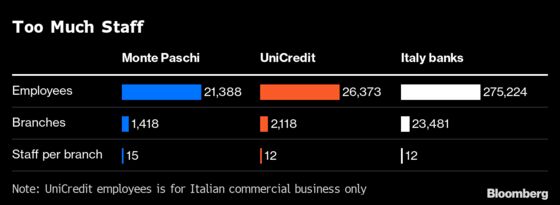

Job cuts were also a key sticking point. Monte Paschi -- nationalized in 2017 -- has one of the highest ratios of employees per branch in the Italian banking system, and unions have vowed to resist anything but small cuts.

That was unlikely to be enough, with analysts estimating that 7,000 positions -- about a third of the staff -- would need to be eliminated to bring the bank in line with Italian peers.

The Italian government will now likely have to ask the European Union for an extension to the year-end deadline for finding a buyer and then recapitalize the bank on its own, said the people.

Like Alitalia, the 549-year-old bank has been a hot potato passed on by successive Italian governments. The saga reflects deeply-rooted sensitivities in the country and risks diverting resources to help recover from the coronavirus crisis.

Because of its 4.5 million clients, 21,000 employees and 150 billion euros in total assets, Monte Paschi has been considered too big to fail. But it’s also politically important. Siena is the heartland of the Democratic Party, a key backer of Draghi’s government.

A sale was needed because Monte Paschi -- the worst performer in European stress tests -- continues to grapple with weak profitability and a legacy of legal risks and loose lending.

Left on its own, the Italian treasury is likely to move forward with much of the deal offered to Orcel. The plan includes a capital injection of about 3 billion euros, the sale of bad loans, closing some branches and carrying out voluntary layoffs of some 2,000 staff, the people said.

That might still only be a temporary fix, with Monte Paschi too small to thrive on its own, according to most banking analysts. The lender, which has turned an annual profit only twice in the last decade, has a higher cost-to-income ratio than almost all of its rivals, and its balance sheet is about 15% of UniCredit’s 1 trillion euros in assets.

Draghi has an interest in resolving Monte Paschi’s future. As governor of the Bank of Italy, he gave his blessing to the ill-fated purchase of Banca Antonveneta SpA in 2007, which set off all the bank’s woes. That means another attempt at a deal is likely once taxpayers fund the cleanup.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.