(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Are you interested in receiving John Authers' newsletter in your inbox? Please subscribe at this link.

Italian bonds have taken another lurch downward as investors respond with deepening concern to the latest political developments. It is common to appeal for calm by pointing out that although investors are demanding ever higher yields on Italian bonds relative to German bunds -- the best financial measure of Italy’s perceived political risk -- they are still nowhere near the levels reached during the worst of the euro zone sovereign debt crisis in 2011.

In another apparently reassuring precedent, there is the argument that the European Union has won all its stand-offs with recalcitrant debtors. There have been some ugly episodes and brinkmanship, but the euro zone has stayed intact and dissident governments have ended up toeing the line.

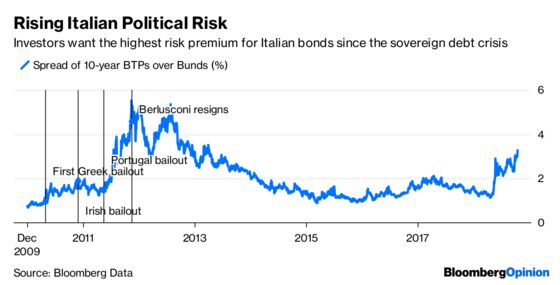

Neither point is anywhere near as reassuring as they might appear. First, it is worth putting political risk in historical context. This is the spread between Italian and German 10-year bond yields this decade:

The spread is currently the widest since early 2013, when Cyprus was briefly a cause of concern. But look at how the spread widened as the crisis took hold in 2011 and 2012 as Italy was lumped in with other debt-laden peripheral euro zone nations, a group that had become known by the PIIGS acronym (for Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece and Spain). There was widespread fear of contagion. Once one country came under speculative attack, others would as well. And yet, the spread now is wider than it was after the bailouts of Greece, Ireland and Portugal. It’s also the equivalent to the level reached in late August 2011, only a matter of weeks before it peaked and forced Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi to resign.

As conditions in the rest of the euro zone periphery are far calmer now than they were then, this latest widening in the yield spread is alarming. Using the euro zone sovereign debt crisis era as a basis of comparison, it looks as though Italy and its $2.67 trillion bond market is now very close to losing the confidence of international investors.

And as for the point that the EU has won its other stand-offs, bear in mind that Greece, Ireland, Portugal and certainly Cyprus are all far smaller than Italy, and that banks in the rest of Europe are deeply intertwined with Italy. When the EU offered Greece a bailout in 2010, banks in the rest of the euro zone had large enough exposures to their Greek counterparts that there was reason to fear a major crisis if a rescue was not attempted. By 2015, when the left wing government of Alexis Tsipras made a serious attempt to rebuff European demands, the European banking sector had largely purged its exposure to Greek banks, freeing the euro zone to take a tougher stance. Greece, which was forced to close its banks for a matter of weeks, eventually accepted the EU’s terms.

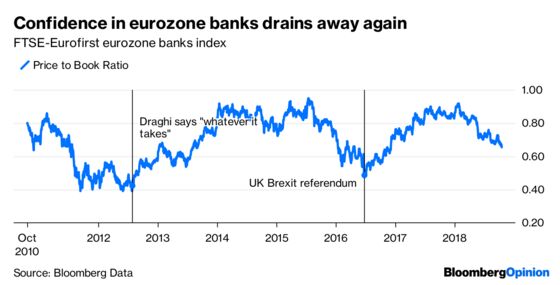

At that point, the price to book ratio of the FTSE Eurofirst Bank index was about 0.9, implying relative confidence in the strength of bank assets. It as since shrunk to 0.65, implying less confidence. True, this measure dropped below 0.4 during the worst of the crisis, before European Central Bank President Mario Draghi promised to do “whatever it takes” to save the euro, but the point remains: confidence in ability of banks to withstand a crisis in Italy is waning, and that weakens the position of European politicians. It also shows that confidence in the euro zone as a whole is deteriorating toward levels not seen since the immediate aftermath of the U.K.’s Brexit referendum in 2016.

The upshot is that the historical auguries for Italy are nowhere near as good as they first appear. The U.K.’s incredible succession of stumbles as it attempts to extricate itself from the EU have inevitably distracted some attention, but the market indicators are flashing a serious incipient crisis in Italy, with no obvious resolution.

Fear of Flying

Two senior economists offered two contrasting visions of regulation in the last 24 hours. Neither was reassuring. But that should not be surprising as one has enjoyed the nickname of “Dr. Doom” for half a century, while the other offered up flying light aircraft as a reassuring metaphor for central banking.

Randal Quarles, vice-chairman for regulation at the Federal Reserve, regaled the Economic Club of New York with the notion that setting monetary policy was like flying a plane. Surely he could have chosen a less alarming metaphor. He pointed to the adage for trainee pilots of “don’t chase the needle.” Even if the needle on the dashboard in front of the pilot suggests that the plane is deviating from its course, they must not “chase” it, or alter their trajectory too quickly. Rather:

The right strategy is to set a course based on your knowledge of the destination, winds, and capabilities of your plane . Then, stick to that course steadily, even as the needle moves from one side to the other. If the needle moves to one side very clearly then you might change, but even then only gradually, with clear communication of what you are doing.

This is in line with the approach to monetary policy that he espoused. He is optimistic on the U.S. economy, which he considers to be in a “good spot” and thinks that the Fed is as close to its dual mandate of low inflation and full employment -- as it has been for a long time. Continuing uncertainty, he said, “reinforces the importance of a clear strategy and a predictable approach to the removal of accommodation.” The idea is to move slowly and steadily.

When questioned on regulation and the Fed’s power to use a “countercyclical buffer” if it wishes -- increasing the capital that banks must keep in reserve when times are good, thus giving them a proper cushion when times are bad -- Quarles seemed markedly unenthusiastic. He said the Fed currently viewed financial risks as “moderate” (meaning, for supporters of counter-cyclical regulation, that this would be a good time to force banks to keep a bigger financial cushion), and that support for higher capital buffers seemed to be more a reflection of the stage that the economy has reached in the business cycle, rather than the level of risk. He added that U.S. banks already have higher capital requirements than those in Europe, leaving U.S regulators with less “headroom” to impose extra capital requirements.

A few hours earlier in Washington, Henry Kaufman delivered a very different message to the National Economics Club. The former Salomon Brothers chief economist has long been an outspoken critic of financial deregulation and of increasing financial concentration in the financial sector. Twenty years ago, he was a lone voice speaking out against the merger of Citicorp and Travelers Group to form Citigroup, a deal that created what was then the world’s biggest financial firm.

Now, he suggests that concentration grown more dangerous since the crisis. His argument is profound, and although he has been making it consistently for decades, the evidence for it has unfortunately grown stronger. Here is his central message:

In contrast to the early postwar decades, financial concentration rose prior to and during the Great Recession and has continued to gain momentum in the recovery. Consider what already has happened. Back in 1990, the ten largest financial institutions held about 10 percent of U.S. financial assets. Today the figure is about 80 percent. To be sure, official policymakers have tried to constrain large financial institutions, which are now deemed “too-big-to-fail.” These behemoths are required to take stress tests, and there are procedures in place for liquidating them in an orderly fashion if they get into serious financial trouble.

At first blush this seems quite reasonable, but it will eventually lead to even greater financial concentration. Who will absorb the balance sheets of the dissolving institutions? Perhaps the federal government will initially, but ultimately their assets will be absorbed by the remaining giant institutions.

These financial conglomerates have taken on a quasi-monopolistic role. They dominate in market making, investment banking, and money management. From my perspective, they are quasi-public financial utilities – too big to fail when the government rescues the markets from their frailties – but they are able to exercise significant financial entrepreneurship during periods of monetary ease. Meanwhile, during periods of monetary restraint, smaller financial institutions experience a disproportionate amount of pressure, and those that collapse typically are absorbed by the too-big-to-fail institutions. The result, again, is greater financial concentration.

All of this is an argument for more intrusive regulation. With the option of splitting up big banks now looking very hard to execute, the Kaufman logic suggests that it is imperative to regulate the behemoths that remain like public utilities. Much like a nuclear power plant, they provide an essential service, with the potential for catastrophe if things go wrong. So, best for the government to make sure that nothing goes wrong. Or, to use the Quarles analogy, best not to let the pilot deviate from the needle, even for a nanosecond.

Maybe a second pilot could sit behind the first and override any attempts to pick up speed or change course. At the very least, they could be fitted with a counter-cyclical buffer.

Meanwhile, Kaufman also draws a link between monetary policy and risk-taking. In his accounting, a policy of steady, predictable, well-flagged tightening, accompanied by upbeat economic assessments (or in other words, exactly what Quarles would offer a few hours later in New York) was a perfect recipe to encourage dangerous speculation:

For its part, the Federal Reserve is now pursuing policies that not only will support further financial concentration but that also will pose significant risks to future financial markets. This is the policy of monetary moderation. The main features of this policy are projections for economic growth, for inflation, and for the likely path of the Federal funds rate. Will the Fed really ever forecast significant change in economic activity such as a recession or jumps in inflation? I doubt it. Up to now, at least, the central bank’s projections have been comforting to financial markets.

In fact, such projections encourage speculation. The Fed’s policy of monetary moderation has had a glaringly speculative impact on corporate finance.

Dr. Doom’s arguments, it seems to me, suggest that the Fed should be prepared to move away from the needle and alert pilots to the possibility that they may be forced to change direction in a hurry. They also suggest that it might be better to leave the aircraft in the hangar while it undergoes major repairs -- even if that means moving slower.

Stepping back from the flying analogies, it is alarming that there is still such a deep division of opinion over the course of monetary policy and regulation 10 years after from an epochal crisis. But a change of course at this stage is very unlikely.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets. Before Bloomberg, he spent 29 years with the Financial Times, where he was head of the Lex Column and chief markets commentator. He is the author of “The Fearful Rise of Markets” and other books.

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.