Italy State Failing Businesses Just When They Need It Most

Italian State Is Failing Businesses Just When They Need It Most

(Bloomberg) -- It’s been six weeks since Eleonora Furlan first asked about an 800,000-euro ($896,000) state-backed loan to save her business, but she still has no idea if she’ll get it. And her seven employees haven’t received any state relief since their temporary layoffs.

“I’m angry I’m not getting a clear answer; I have no Plan B,” said Furlan, the 42-year-old owner of Pregi Srl clothes wholesaler near Turin in northern Italy.

Forced to close by a national lockdown to counter the coronavirus in early March, Furlan is among the legions of Italians caught between a dysfunctional state and a deeply scarred banking system as they deal with the pandemic’s devastating impact on the European Union’s third-biggest economy.

The loan delays are partly a result of some banks dragging things out because of strict procedures they are reluctant to ignore and their concern about timely reimbursement, according to a senior Treasury official who asked not to be identified in line with policy. Government squabbling and a circuitous bureaucracy haven’t helped the situation.

As a result, the loan program has delivered about 0.1% of the 400 billion euros it promised, according to a joint statement of the task force including the Bank of Italy and Treasury.

Of the 8.2 million workers for whom firms have requested emergency unemployment benefits, only 2.6 million have been paid by the Inps agency. Companies have advanced money for 4.2 million workers, while 1.4 million workers haven’t received any relief since March, according to data on the Inps website.

The Italian government is preparing a formal request to European authorities for access to the SURE fund to help pay for unemployment measures, daily la Repubblica reported Thursday.

The rush to register made a complex system even slower, especially with many Inps employees out due to the lockdown, according to the Treasury official.

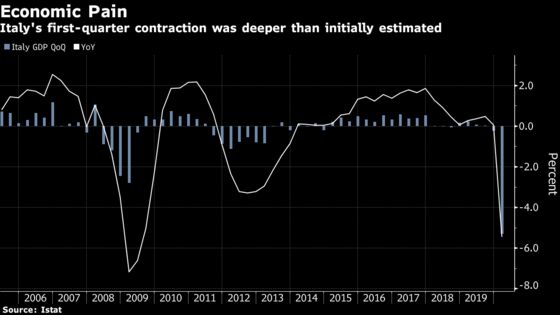

Italy’s failings are undermining Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte’s attempt to persuade EU partners to boost their help to Rome. Efforts to salvage an economy which the European Commission sees shrinking 9.5% this year have been plagued by a litany of missteps: cabinet meetings repeatedly postponed; decrees leaked to the press, then haggled over by coalition parties, only to be further amended in parliament; government attacks against banks; banks retaliating against the government.

EU leaders are considering a 750-billion euro recovery plan that sees Italy as the main beneficiary. But central bank Governor Ignazio Visco warned last week that, in return, Italy will have to undertake structural reforms and fix long-standing issues including its byzantine system of laws and procedures that’s causing some of today’s delays in aid to citizens.

The recession and a mammoth debt burden, which is seen climbing well past 150% due to stimulus spending worth 75 billion euros since March, are raising investor concern about debt sustainability.

The European Central Bank has stepped in with emergency bond buying to cap spreads between countries and protect weaker nations like Italy from market speculation.

Read about Italy’s surprise bond sale with $100 million in bids

All this comes at a time when Conte’s coalition is taking an increasingly interventionist stand in businesses including flagship airline Alitalia. Conte’s administration is tangled up with big business over the virus-linked loans too, with a request for highways operator Autostrade per l’Italia tied to a dispute over concessions. A potential 18.5 billion euros of additional backed loans are under review, including a 6.3 billion-euro credit facility for Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV.

But across Italy, the loans aren’t reaching the businesses that need them most, or if they do, they come after lengthy delays. The guarantee fund for smaller firms has so far authorized loans worth more than 22 billion euros, a fifth of what the government had projected.

Conte in late April appealed to banks for “an act of love” to speed up their response to the loan requests and said last month that the government’s liquidity decree allowed for guaranteed loans to be delivered in 24 hours.

Yet the delays have endured. “The same measures continue to be applied differently by some banks, which shows that it’s not the measures themselves that are preventing state-guaranteed loans being granted rapidly and efficiently,” Finance Minister Roberto Gualtieri told lawmakers on May 26.

Italians seem unimpressed with the excuses. The share of voters who back the government has fallen to 34.8% from a virus emergency peak of 37.1% in late March, according to a survey by Euromedia Research published by newspaper La Stampa on May 26, while Conte’s personal popularity is down to 44.3% from 48.1%.

Furlan says she spends part of her time cycling to work swearing to herself. She needs her loan to help pay for 900,000 euros of Spring-season stock she can no longer sell or risks having to close.

“My bank helped me a lot, but there was so much paperwork and checks that I sent in the completed loan application in mid-May,” said Furlan. “Then the government said the loan could be for 10 years instead of six, so I had to file a new application.”

The banks point the finger at the government. Its procedure is so complicated that it’s difficult for lenders to grant loans quickly, even those up to 25,000 euros for which the state gives a 100% guarantee, bankers say. It’s even more complex for loans above 25,000 euros, which are only partly guaranteed by the state, they say. Lenders have to follow a standard procedure opening a filing, making checks on credit history, collateral and risk.

Some branches understood that giving the state-backed loans under 25,000 euros was a waste of time because they wouldn’t feature in their budgets for their annual goals, said Massimo Masi, general secretary of Uilca, a union that represents bank employees.

In other cases, banks tried to push clients to use guaranteed funds to repay old debt in order to transfer risk to the state, or cherry-picked in selecting clients, by asking for large numbers of documents, slowing processes, Masi said.

Giovanni, a furniture shop owner in the southern region of Calabria who asked not to be identified by his surname, was one of the luckier ones. He applied for a 25,000-euro state-backed loan on April 10 and received it on May 15.

“It was a nightmare,” he said. “I had to wait more than a month to get money that was supposed to be given in a couple of days.”

While the Bank of Italy acknowledged some lenders were slower in giving credit because of organizational problems and differences between banks’ IT systems, it stood by the need for credit assessments.

“In the absence of any explicit regulatory provisions, banks that fail to conduct a creditworthiness assessment expose themselves to the risk of committing a crime,” Visco said in a May 29 speech.

At her warehouse outside Turin she tentatively reopened last month, Furlan is still waiting to hear on the loan.

“My bank says I might get a reply at the end of June,” Furlan said. “I don’t know if I can hold out that long, or what I’ll do if I don’t get the money.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.