It’s Kraft vs. Kraft in Venezuela’s Strange Take on Capitalism

It’s Kraft vs. Kraft in Venezuela’s Strange Take on Capitalism

(Bloomberg) -- What’s left of Venezuela’s manufacturing sector has survived government expropriations, frequent blackouts, a currency collapse and equipment shortages. But now there’s another threat: competition from imported versions of the companies’ own products.

Shops across Venezuela stock Mexican-made Oreo cookies right next to the locally produced version. Kraft Heinz Co.’s mayonnaise is being imported from Brazil and the U.S., even though the company also makes the sandwich spread in the city of Valencia. Fifty-pound bags of American-made Purina dog food compete with the same product from Nestle SA’s plant in Aragua.

The imports, which are exempt from customs duties and value-added taxes, can be as much as 40% cheaper than the locally produced version even after shipping costs are included. Local factories just can’t compete given the extreme inefficiencies of doing business in Venezuela.

The situation is part of the absurd nature of capitalism in Caracas, where President Nicolas Maduro is encouraging the use of the U.S. dollar and easing price controls to revive an economy ravaged by hyperinflation, sanctions and years of mismanagement.

Allowing the duty-free imports for some 2,500 items was intended to help ease shortages. And while there are signs the Maduro administration is beginning to recognize the problems for domestic factories, there’s also a booming cottage industry for mom-and-pop companies that buy from overseas middlemen and then resell the goods to retailers.

“The government has said the priority is the local industry, but what they are doing right now is subsidizing foreign economies,” said Luigi Pisella, the president of Conindustria, a group that represents manufacturers. He says the imports are among the biggest challenges for his members.

As with much of the nascent private enterprise that’s bubbling up in Maduro’s socialist Venezuela, some of the imports of retail goods are technically illegal, as door-to-door international shipments are supposed to be limited to private consumption, not items for resale. But the government turns a blind eye to the trade. According to industry estimates, door-to-door shipments now represent 40% of total imports, doubling since 2017.

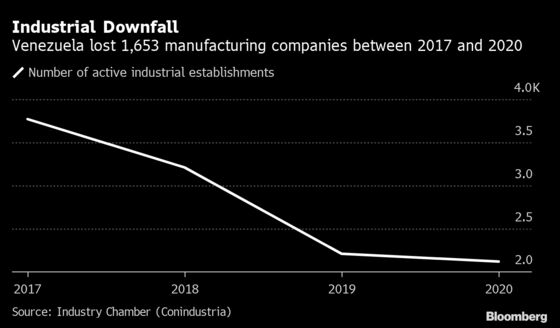

The practice is adding to stress for an industrial sector that’s shrunk by almost half over the past few years as a shortage of raw materials, a lack of parts for heavy equipment, a collapsing currency and an economic wipeout that slashed consumers’ spending power sapped profit.

Between 2017 and 2020, the number of manufacturers in the country shrank 44% and more than 1,600 factories closed amid one of the worst economic crises in modern history. Firms including Kimberly-Clark Corp., Kellogg Co., Cargill Inc., Pirelli SpA and Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. have exited the country in the past five years.

After years of complaints from factory owners, the Maduro administration finally acknowledged the toll the imports are taking last week, announcing it will cut almost 600 items from the tax exemption list, including some types of pasta, milk and detergents. The country aims to gradually replace all imports with domestic products, Vice Presidency Delcy Rodriguez said.

Nestle, one of the few remaining multinationals still operating in the country with five factories and about 2,500 employees, says it’s losing sales to the gray-market imports. It has warned about potential health risks from the non-authorized versions of its products, and says some of them are counterfeits, including fake Nido milk powder.

“Tax exemptions are putting us at a disadvantage,” said Francisco Guerrero, Nestle’s vice president of legal issues in Venezuela. “But what worries us the most are the products that don’t comply with legal and health regulations, with no traceability. Or worse, forgeries.”

Changing Patterns

While local manufacturers bemoan the situation, consumers have benefited. Store shelves barren just a few years ago are now overflowing with choices. Everything form Italian olives to Cheesecake Factory snacks are available at convenience stores, known as bodegones, some of which are so flush with goods they resemble supermarkets.

Retailers are drawn to the imported versions not only because of the price, but also to offer more variety, as local products usually come in fewer sizes due to production constraints. Of course, poverty is widespread and higher-end food products are unaffordable for many Venezuelans. According to a recent survey, the average worker’s salary is the equivalent of about $55 a month.

Although foreign items are often cheaper, stores usually offer the local version as well to satisfy customers loyal to a particular taste. They are also easier to restock.

When everyday goods were harder to find just a few years ago, consumers were happy to locate any version of the product they wanted. Now, shoppers have the luxury of seeking out other variables such as preferred brands and sizes, said local market researcher Alexander Cabrera of Atenas Consulting Group.

Iris Origuen, 58, acknowledged that goods made abroad are often of higher quality and cheaper as she took a break from her job at a nail salon to shop at a bodegon in a residential neighborhood in Eastern Caracas. But she said there’s just something about the taste of some local foods that keeps her coming back.

“With some products like mayo, I wouldn’t trade the Venezuelan one,” Origuen said.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.