It’s Deja Vu All Over Again as Eastern Populism Rattles Banks

It’s Deja Vu All Over Again as Eastern Populism Rattles Banks

(Bloomberg) -- As an east European credit collapse threatened to topple western parent banks in 2009, policy makers across the east-west divide pulled together for the first time to save the system. A decade later, with eastern lenders outperforming the richer west, new risks are forming that threaten to be just as damaging.

Bankers are meeting in the Austrian capital on Wednesday to discuss the 10 years of the Vienna Initiative, founded to help ring-fence the region against the global economic crisis. The backdrop to their talks is a landscape of rising political populism that may still rock the financial system and a growing money-laundering scandal that has already shaken parts of eastern Europe and western banks such as Swedbank AB and Danske Bank A/S.

“I think both these things should be a concern for the Vienna Initiative,” said Erik Berglof, the director of the London School of Economics Institute of Global Affairs and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s chief economist in 2009. “This whole populist pressure has sort of spread throughout the region. If you really get a more serious downturn, these issues will come to the fore. And I am really worried about that.”

Thirty years after the fall of the Iron Curtain, banking from Tallinn to Tirana and Bratislava to Brest-Litovsk is still dominated by a group of western European banks led by Austria’s Erste Group Bank AG and Raiffeisen Bank International AG, Italians UniCredit SpA and Intesa Sanpaolo SpA, France’s Societe Generale SA and Belgium’s KBC Groep NV, who rushed into the region hoping to profit from its catch-up with the west. Of their eastern competitors, Budapest-based OTP Bank Nyrt has joined them after a cross-border acquisition spree.

And it’s that very cross-border relationship that can prove to be an Achilles heel to the development of free-market economies in a banking system that is more intertwined than ever. Without the willing partnership of both sides -- western banking executives and eastern policy makers -- the financial system remains vulnerable to crises.

“Only coordination leads to an optimal result, this is the message we need to keep,” said Austrian central bank Governor Ewald Nowotny at the conference. “This is a very important lesson that we can learn from the Vienna Initiative; that coordination pays. Unfortunately, today there is a bit of coordination fatigue.”

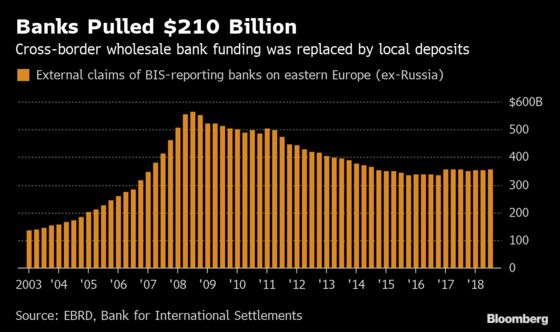

Before the global financial crisis, parent banks borrowed cheaply in the west and lent at emerging-market rates to consumption-hungry eastern clients purchasing homes, cars, and refrigerators. Economic catch-up was seen as a one-way street and neither risk management nor money-laundering prevention was a focus.

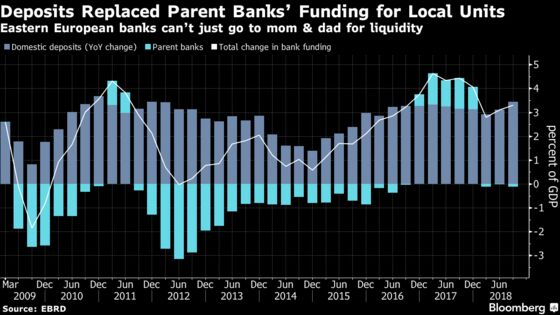

Under the Vienna Initiative, banks shifted toward local-currency lending and non-performing loans were massively written down, at great cost to the banks who’d granted them in exuberance. Overall, that’s left both eastern consumers and western banks less vulnerable to credit crunches similar to what rocked the region in 2009, according to the EBRD.

“Before 2007 there was a lack of local funds and therefore it was necessary to bring in cross-border quite a lot of money,” Raiffeisen Chief Executive Officer Johann Strobl said Wednesday. “We’ve been blamed for bringing over-indebtedness to some of the countries, but I think this is digested now and the development is balanced and solid.”

“Banks are increasingly asked to stand on their own two feet and not depend on mom and dad for financing,” said Francis Malige, who leads the EBRD’s investments in the financial sector.

After several years of deleveraging, shrinkage in many countries and billions of losses as boom-time loans went sour, the tide has turned in most eastern European countries, as Andreas Treichl, chief executive officer of the region’s biggest lender, Erste, boasted when he presented record annual results in his Vienna headquarters last month.

“We’ve got growth rates that other European banks can’t have, because of the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Hungary, Romania,” Treichl said.

Strong Cycle

So far at least the economic cycle is strong enough to provide a sufficient pool for bank funding. Concerns that the reduction in cross-border wholesale funding would curb growth haven’t materialized, according to Artur Szeski, a banking credit analyst at FitchRatings in Warsaw.

“Wages are growing, unemployment is falling and so disposable incomes are growing very fast, and a significant part of that goes into bank deposits,” Szeski said. “Liquidity is not a constraint for growth at all, and neither is capital.”

Growing profits have invited a new risk, as recent events in Romania demonstrated. There the government introduced a draconian “greed tax” on banks. While Bucharest had to eventually curb the levy, the episode underscored challenges that can be more difficult to fix than the credit crisis.

“The past year made clear that political risk outweighs commercial risk,” Erste’s Treichl said.

Romanian Gambit

Bucharest’s attempted raid on banks’ repaired balance sheets wasn’t the first or the only one. It took a cue from Hungary, where the newly elected Prime Minister Viktor Orban had to deal with a particularly toxic mess in 2010. Austrian banks had exported to their eastern neighbor the dangerous lending habit of mortgages denominated in Swiss francs, bringing millions of Hungarians into calamity when the forint crashed.

Orban turned Hungary into the laboratory for the political risk that still haunts banks. He was the first to realize that it pays to milk foreign banks considered predatory. And he called the banks’ bluff when he bet that they wouldn’t dare pulling out in retaliation for government actions that hurt their balance sheets.

“Orban won,” said Matthias Siller, who manages the $887 million Baring Eastern Europe fund. “He ignored the threat that the banks would pull out and won. And that makes him a bit of a model for the rest of eastern Europe, which is somewhat dangerous for the banks.”

Hungarian Inspiration

Orban’s actions continue to inspire politicians in eastern Europe. One reason for that popularity is that voters in some countries still suffer from practices they perceive as unfair to borrowers. Poland is currently discussing raising funds for the conversion of foreign-currency loans that could cost banks 3.2 billion zloty ($842 million) per year.

“Sticking our heads in the sand does not work, closing borders does not work,” Thomas Wieser, the former president of the EU’s Economy and Finance Committee who led the influential Euro Working Group, said Wednesday. Otherwise, “we will go back to the stone age of European integration.”

However annoying for banks and their investors, the fact that banks have become a target for tax-hungry governments is also just the flip side of the coin, EBRD’s Malige said.

“A profitable industry is going to invite appetite,” he said. “I’d rather have it that way around than banks being all loss-making and inviting stability measures for support.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Boris Groendahl in Vienna at bgroendahl@bloomberg.net;James M. Gomez in Prague at jagomez@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Chad Thomas at cthomas16@bloomberg.net, Balazs Penz, Peter Laca

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.