Inside the Secret Banking Heavyweight That Aims to Revive Italy

Inside the Secret Banking Heavyweight That Aims to Revive Italy

(Bloomberg) -- Something is changing at Italy’s state bank.

The Treasury offices next door have the same sense of dated grandeur you’ll find at any ministry in Rome. But step into the white, airy lobby of Cassa Depositi e Prestiti SpA and there’s a distinctly corporate vibe in an entity few Italians are aware even exists.

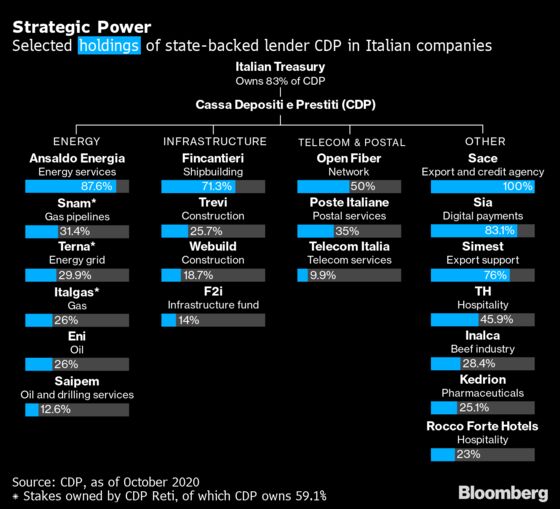

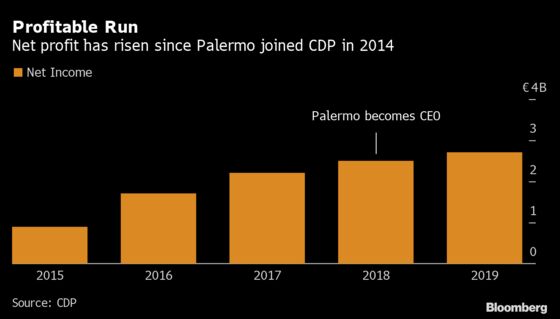

Since taking charge in 2018, Chief Executive Officer Fabrizio Palermo has sought to erase the staid bureaucracy found in other government buildings. He’s been reengineering CDP to put its 474 billion euros ($556 billion) of assets to work supporting Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte’s industrial strategy. But the 49-year-old also aims to be taken seriously as a private investor after hiring a clutch of investment bankers from top international firms.

Whether he succeeds or not, the transformation of the state-backed lender and equity investor marks a watershed for the Italian economy with the return of the state as a major player in corporate life, reversing the privatizations that former European Central Bank President Mario Draghi pushed through in the 1990s as the head of the Treasury.

“We interact daily with both private and public counterparties, working well with both sides,” Palermo said in an interview in his office this week. “This is part of our strength.”

It may also be one last roll of the dice for a country that has sunk steeper into debt with successive crises, leaving the government dependent on support from the ECB and the European Union.

While Conte has been battling to contain the coronavirus and keep the economy afloat, Palermo has done almost 10 billion euros of deals since the summer, taking a stake in stock market operator Euronext SA and becoming the biggest investor in payment services provider Nexi SpA. CDP is also negotiating to take full control of Open Fiber SpA, to feed into Conte’s plan for a national broadband provider to underpin the shift to a more digital economy.

His most contentious deal may be a bid for Atlantia SpA’s highway network Autostrade per l’Italia. A deal would resolve Conte’s two-year struggle to separate Atlantia from its toll road business after the fatal collapse of a bridge in Genoa, but the negotiations highlight the tensions between CDP’s commercial objectives and the political concerns of its masters.

Jonathan Amouyal, a partner at TCI Advisory Services LLP which owns about 10% of Atlantia, accused the government of trying to “punish the rich.”

“This is likely to have negative consequences for Italy. Investors will remember,” Amouyal said in an interview with Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung.

CDP executives argue that the presence of Macquarie Group Ltd and Blackstone Group Inc. as co-investors is a sign that the bank attracts private capital with its ability to navigate the Italian system. Each euro that CDP puts into a deal typically attracts 2.50 euros from private, often foreign, investors.

But despite the political pressure it’s facing, Atlantia rejected CDP’s latest offer and the bank’s approach to the deal offers some evidence to those worried that the bank is acquiring too much power and could be subject to more heavy-handed interference down the line.

At a recent meeting, Pierpaolo Di Stefano, whom Palermo hired from Citigroup Inc. last year to run CDP’s investment arm, insisted that the bank must ignore government calls to cut highway tolls if the deal goes through, according to people with knowledge of the discussions. His boss insisted they should be willing to listen, the people said. The decision is ultimately made by the Italian government.

The challenge for CDP is to find a way to knit together those two world views — Palermo is Rome-based and astute at navigating the political currents of the capital, whereas Di Stefano has spent much of his career in Milan and is more comfortable talking to international investors and the business leaders of Italy’s industrial north, according to people who know them both.

Those differences were set aside on the first weekend in March when Palermo called his divisional heads to an emergency meeting in Rome as the economy was heading into lockdown.

The modernization of the bank’s systems had already laid the groundwork for remote working with a shift from paper-based to digital processing for loans. But Palermo told his executive team that they would have a role to play in helping Italy get through the crisis.

CDP provided 16 billion euros of support to Italian businesses and public institutions and renegotiated 30,000 loans despite the fact that staff were working from home. Three years earlier, the head of finance had had to return to the office after an earthquake scare so he could close out the bank’s positions.

Cassa Depositi was set up by the Parliament of the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1850, 11 years before the Italian state was born, and for much of its history it was a snoozy bureaucracy, managing the savings of everyday Italians collected through the post office network.

Since the Institute for Industrial Reconstruction, the state’s industrial arm, was dissolved in 2002 after becoming a by-word for public mismanagement, Italian governments have often looked to CDP when they wanted to throw their weight around on the economy. Former Finance Minister Giulio Tremonti used to call it a “sleeping giant.”

Palermo was the type to wake it up, beginning his career at McKinsey & Co. before joining Fincantieri, the state-owned defense manufacturer. In 2014, he became chief financial officer at CDP and CEO four years later.

Taking charge a month after Conte was installed at the head of a shaky coalition, Palermo owed his appointment to the anti-establishment Five Star Movement but he quickly won the confidence of the League, Five Star’s first partners in government, according to people who’ve seen him operate up close. When the League quit the government, he established a relationship with new finance minister from the Democratic Party, Roberto Gualtieri.

With high-level backing from the government, Palermo shifted CDP’s focus to large deals, beefing up its influence in corporate Italy, but also working to change the culture of the organization.

His first business cards gave the bank’s address as the prestigious Via Goito, even though that entrance was reserved for staff and visitors had to find another door on a side street. He ordered the main entrance to be rebuilt to create the right first impression.

To execute his plans, he hired 220 additional staff, including several senior bankers, selected from more than 50,000 applications. Several agreed to significant pay cuts in order to join Palermo’s project, according to people familiar with the matter.

In December 2018, Palermo produced his three-year plan to direct Italy’s abundant domestic savings to more productive investments and support the government’s plans to revive the economy.

Produced in English like a typical investors’ presentation, it was the sort of professional marketing that would have previously been unthinkable for Italian bureaucrats.

“I focused on two things: the balance sheet and the people,” Palermo said. “We have totally rethought CDP.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.