Inflation Is Nowhere in Sight

Inflation Is Nowhere in Sight

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Fearing that low unemployment would spur serious inflation, the Federal Reserve has raised its benchmark interest rate nine times since December 2015 and has started to shrink the size of its balance sheet assets in an effort to tighten credit. So imagine the surprise when the minutes of the Fed’s December monetary policy meeting stated that “many participants expressed the view that, especially in an environment of muted inflation pressures, the committee could afford to be patient about further policy firming” (emphasis added).

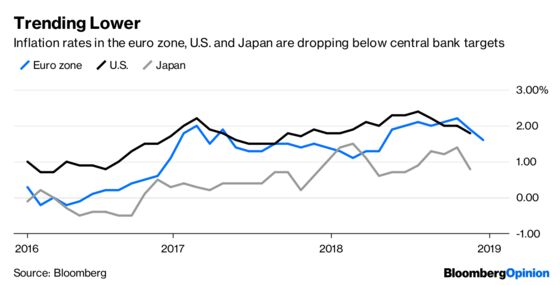

This is more than policy makers looking to send a dovish signal in an effort to calm turmoil in the financial markets. Inflation is nowhere in sight, either in the U.S. or globally. The Fed’s preferred measure, the personal consumption expenditures deflator, rose 1.8 percent in November from a year earlier, below the central bank’s 2 percent target. Treasury securities indexed to inflation returned less in 2018 than conventional U.S. debt. Also, bond-market expectations for the average inflation rate in the next decade dropped from 2.2 percent last spring to 1.7 percent at year-end.

The European Union’s consumer price inflation fell from 1.9 percent in November to 1.6 percent in December. The Bank of Japan has given up on hitting its 2 percent inflation target. Reflecting price deceleration, 10-year Chinese government bond yields have dropped to 3.12 percent from 4 percent a year ago.

Higher American wages, up 3.2 percent per hour in December from a year earlier, will probably continue to have little effect on prices. Globalization has flooded the West with cheap goods from China and other lower-cost Asian economies, and should continue unless President Donald Trump builds a sky-high tariff wall all around America.

The “on-demand” economy is highly deflationary, with average cab ride fares dropping 58 percent since the advent of Uber and Lyft, according to a Wall Street Journal analysis in September. In New York City, as Uber cars replaced licensed taxis, the price of the required medallion dropped from $1 million in 2003 to under $200,000. High-paid union jobs continue to disappear, with 6.5 percent of the private sector workforce unionized versus 25 percent in the early 1970s.

After skyrocketing for decades, the average annual net cost at a four-year public college or university actually fell 0.2 percent in 2018-2019 from a year earlier as student debt burdens led to a drop in enrollment, according to the College Board, the nonprofit that administers the SAT and tracks university costs.

The popularity of online retailing is highly deflationary, and the downward pressure will intensify as Amazon.com’s purchase of Whole Foods squeezes other grocers. Proctor & Gamble and other big-name brands are seeing their pricing power slip. Apartment rents are being curtailed ahead of some 319,000 new units scheduled for completion this year. Drug prices are being reined in as the Trump administration plans to reduce costs for some Medicare drugs by basing them on the lower costs in other countries. Investment managers are in a race to see who can cut fees the most.

With slowing economic growth here and abroad, deflationary forces should intensify, especially with global total debt at a record relative to gross domestic product. The World Bank and International Monetary Fund have both revised lower their forecasts for worldwide economic growth this year and next.

In this climate, I rate a recession this year at a two-thirds probability with the other third being slower growth. The Fed cut its 2019 growth forecast from 2.5 percent to 2.3 percent and Wall Street analysts, who usually follow the parade down, expect earnings for members of the S&P 500 Index to rise 7.8 percent, way down from their September forecast of 10.1 percent growth. For the last quarter, they’ve slashed their estimate from 17 percent year-over-year growth to 11 percent.

Stocks, commodities and bond yields have rebounded from their December swoon, but I’d use this as a selling opportunity. Equities are a long way from recession-related bottoms, and even defensive sectors such as utilities, consumer staples and health care have not held up.

With slowing global growth, supplies of commodities will be even more ample, depressing prices further. I like copper on the downside since it’s used in almost every manufactured product ranging from machinery to autos to plumbing fixtures and, therefore, reflects worldwide production. Chinese consumes about half the world’s annual copper supply, and with slowing growth there, the price is down 21 percent since last June.

Treasury bonds have done amazingly well in the face of Fed tightening, probably in anticipation of a recession and slower inflation — if not deflation. With the Fed on hold and their haven appeal in a sea of worldwide uncertainty, the yield on the 30-year Treasury bond may drop toward my long-held target of 2 percent from about 3 percent currently. That would represent a 20 percent gain in the price of the bond.

The U.S. dollar also has haven appeal. That’s bad news for U.S. exporters and multinationals that suffer currency translation losses as the greenback strengthens. Ditto for emerging markets, whose huge dollar-denominated debts take more local currencies to service. Also, since almost all internationally traded commodities are dollar-based, their import costs will continue to leap.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Robert Burgess at bburgess@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

A. Gary Shilling is president of A. Gary Shilling & Co., a New Jersey consultancy, a Registered Investment Advisor and author of “The Age of Deleveraging: Investment Strategies for a Decade of Slow Growth and Deflation.” Some portfolios he manages invest in currencies and commodities.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.