Billionaire Glasenberg’s Last Deal Says Coal Isn’t Dead Yet

In Last Deal, Glasenberg Bets on Coal’s Long, Lucrative Twilight

(Bloomberg) -- Ivan Glasenberg is Mr. Coal. The most successful commodity trader of his generation built his career on slaking the world’s thirst for cheap energy with countless shiploads of the fossil fuel, a trade that made him both the boss and biggest shareholder at Glencore Plc.

Now, Glasenberg is on his way out, stepping down this week after almost two decades as chief executive officer of the resources giant. As the world navigates the transition to a low-carbon energy system, many expect coal to head the same way, replaced by huge investments in solar and wind power.

But in his last days on the job, Glasenberg made one last coal deal, spending $588 million buying out the partners in the Cerrejon mine in Colombia. His parting act shows why expectations of coal’s swift demise are likely to be confounded and how mining the black stuff could remain vastly profitable for years to come.

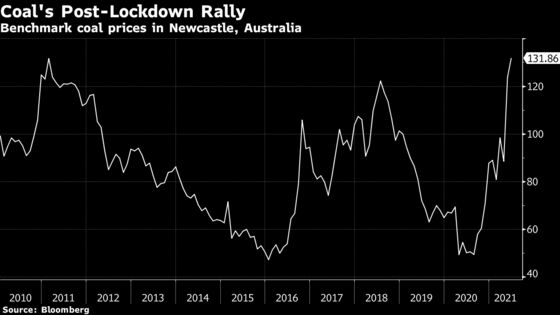

For the world leaders working on strengthening pro-climate policies at this year’s COP26 summit in Glasgow, it highlights an awkward truth: the coal industry is booming. Prices are at a thirteen-year high as recovery from the pandemic revives power use around the world. China, which burns half the world’s coal, has been forced to try and cool the market. In the U.S., where coal has been on the retreat over the last decade, consumption is expected to rebound 16% this year. Even in Europe, coal use is inching up as demand stretches electricity grids.

The question, both for investors tracking the progress of the energy transition and the health of the planet, is how long it lasts.

Even Glencore doesn’t think coal will be around for ever –- under pressure from fund managers they have set targets to reduce consumption and promised to close their mines within the next 30 years. The number of planned coal-fired power plants around the world is falling as banks refuse to finance their construction and renewable projects can more than hold their own cost-wise.

But Glasenberg, and his successor, Gary Nagle, clearly believe it will be long, lucrative twilight.

“The world has said we want to reduce the amount of thermal coal production, mining companies are definitely not investing in more thermal coal mines,” Glasenberg said at the Qatar Economic Forum last week. “What you are having is supply being disrupted, no new supply coming into the market. However, demand is still there.”

The key driver of demand remains Asia. Despite President Xi Jinping’s pledge to make the economy net zero by 2060, power stations are burning at full capacity this year as demand from factories strains the power system. A peak isn’t expected until 2026 and in the meantime the International Energy Agency forecasts demand will keep rising by about 0.5% a year. Consumption is expected to rise even faster in India, by an average of 3.1% a year.

Together with hefty increases in Southeast Asia, that’s more than enough to cancel out falling burn rates in Europe and the U.S. The IEA reckons the world will consume slightly more coal in 2025 than this year.

Benchmark prices in Australia have rallied about 66% this year to more than $136 a ton, the highest since 2008.

Supply won’t respond because investing in new mines has become anathema for banks and many mining companies. Many owners want to divest the coal assets they already have.

Glencore was able to snap up Cerrejon, once seen as one of the world’s best coal mines, because Anglo and BHP were desperate to exit.

For both the companies thermal coal is a small part of their businesses, dwarfed by commodities like iron ore and copper, and the investor pressure was not worth the economic benefits of staying in the business. Anglo’s CEO Mark Cutifani has already conceded that they’d missed the boat on getting the best returns for the asset. And the complicated structure of the Cerrejon joint venture meant there were few other buyers available.

“BHP and Anglo were essentially forced sellers,” said Ben Davis, an analyst at Liberum Capital. “The best thing about these coal prices, is that there is going to be no supply response coming.”

For Glencore, that means the company forecasts it will make back the cost of the deal within just two years, leaving them another eight years or so to profit from the mine before it finally stops production .

To benefit from being the world’s biggest coal shipper, it must keep increasingly agitated shareholders on side. As pressure builds on investors to align their portfolios with global climate goals, it’s possible they will force to Glencore get out of the business sooner than management would like.

They have already made Glencore cap its coal production, meaning any further acquisitions are unlikely and the company has sought approval from climate-focused investors for its recent coal decisions in a way that would have been unthinkable even five years ago.

There are also signs that many investors are still willing to bet on coal. Earlier this month Anglo spun off its South African mines into Thungela Resources. Despite early investor churn, the stock has soared about 75% in Johannesburg from its first-day close as shareholders are drawn to a healthy dividend yield.

Other companies are also looking to benefit from coal’s slow phase out. A vehicle proposed by Citigroup Inc. and Trafigura Group has been sounding out investors about picking up coal mines and running them to exhaustion, paying handsome dividends in the process.

It’s little surprise Glasenberg, who bought coal in mines in the 1990s when few others wanted them and made billions, has made one final wager.

“You will have coal at these high levels,” he said last week. “That’s what happens when you cut supply and haven’t found a solution for demand.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.