What If That Bond Issuer Never Meant to Pay You Back?

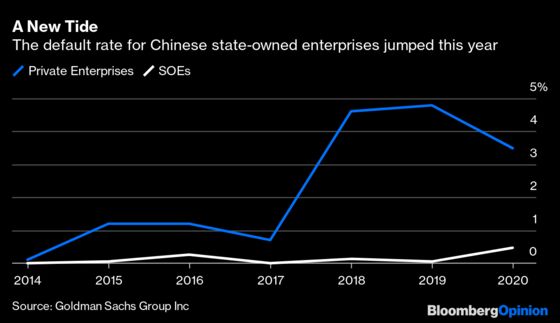

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- China’s $4.1 trillion corporate bond market can be tricky to navigate. If 2018 was known as the year private businesses started to fumble, this one will go down for its wave of ugly defaults among state-owned enterprises. Some are so unseemly that even state banks are cutting their exposure.

A default, on its own, is unpleasant but not unacceptable — this is a risk bond investors are prepared to take. But what if some issuers never meant to pay you back in the first place? There’s now a deepening suspicion that SOE companies will just move good assets out before creditors drag them to court. Two recent examples illustrate why investors are nervous.

Consider Brilliance Auto Group Holdings Co., the parent of BMW AG’s joint venture partner in China. This SOE, owned by the northeastern Liaoning provincial government, has been busy since it first defaulted on a 1 billion yuan ($151.4 million) bond on Oct. 23. Two weeks later, its entire 30.43% stake in a Hong Kong-listed subsidiary, worth about HK$11.1 billion ($1.43 billion), was pledged to “an independent third party” for loan facilities. Brilliance Auto has about 17.2 billion yuan of domestic bonds outstanding.

Good luck getting your money back. In late September, the Liaoning SOE had already transferred that stake to another subsidiary. In other words, instead of asking Brilliance Auto to sell its Hong Kong stocks to repay investors — a fairly easy request — bondholders are now looking to somehow claw assets from a subsidiary’s subsidiary, and the stakes are pledged out, anyhow.

Yongcheng Coal & Electricity Holding Group Co., an SOE in Henan province, made a similar move. The coal miner defaulted on a 1 billion yuan note on Nov. 10. In a filing the previous week, the company said it had transferred HK$1.3 billion worth of shares in Hong Kong-listed Zhongyuan Bank Co. to other companies for free. Yongcheng has 24.4 billion yuan of bonds outstanding.

Unless Yongcheng gets scolded by the regulators, investors have little hope. To protect buyers, bond prospectuses often have clauses on whether companies can transfer major assets. But in this case, the bar is set high at 10% of net assets, according to China International Capital Corp. Yongcheng’s stake in the regional bank isn’t big enough to trigger the protective clause.

Even though China’s bonds are defaulting at a gradual pace, the recovery rate, or how much you can expect to get back, has been falling off a cliff. More SOE defaults will only push that rate lower.

Compared with these SOEs, private enterprises such as China Evergrande Group almost look like fallen angels. Sure, they live dangerously with billions of dollars in debt. But at least they want to survive. With debt-to-equity swaps, quicker turnover and asset sales, the likes of Evergrande are keen to diffuse ticking bombs and pay investors back, because they need debt markets to be open to keep their operations going.

The same can’t be said of SOEs. They seem happy to throw in the towel, or even go for a court settlement — so long as their quality assets are hidden away. These fresh SOE default cases only further my point last week: If you’re just looking at well-behaved default rates, Asia’s junk bond market might seem attractive. The reality is more nuanced. It’s this ugly fat tail that drags investors into known unknowns. Asia's higher yields are not excessive.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Shuli Ren is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Asian markets. She previously wrote on markets for Barron's, following a career as an investment banker, and is a CFA charterholder.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.