In American Theater, a Radical Accounting of Race and Privilege

In American Theater, a Radical Accounting of Race and Privilege

(Bloomberg) -- The necessary changes are so big, Broadway’s leaders are having trouble putting words to them.

Lin-Manuel Miranda, the writer of Hamilton, did not return calls for comment for this story. Jordan Roth, the president of Jujamcyn theaters, did not return calls for comment. Oskar Eustis, artistic director of the Public Theater, declined comment. Jeremy O. Harris, the playwright behind Slave Play who tweeted that megaproducer Scott Rudin “loves to be loudly racist,” declined comment.

Michael R. Jackson, who just won a Pulitzer Prize for his musical A Strange Loop, said the topic “sounds interesting” but declined to officially comment, saying that he was not ready to speak. Charlotte St. Martin, president of the Broadway League, whose board is 96% White, declined to issue a fresh comment but rehashed a recent public statement that read, in part: “We need to first listen, and to be willing to have difficult conversations.”

This is a story about Broadway, Black Lives Matter, their entwined issues of accountability, community, expression, fairness, and what comes next. The inflection point began with the We See You White American Theater letter, which debuted from anonymous origins on June 8 and immediately set the theater world ablaze.

What began as a viral list of racially charged industry grievances, cosigned by more than 300 industry luminaries that included Viola Davis and Billy Porter, became a platform for a variety of reform plans and initiatives.

The “We See You” Letter

A sample point from the missive reads: “We have watched you amplify our voices when we are heralded by the press, but refuse to defend our aesthetic when we are not, allowing our livelihoods to be destroyed by a monolithic and racist critical culture.”

Another: “We have watched you harm your BIPOC [Black, indigenous, and other people of color] staff members, asking us to do your emotional labor by writing your Equity, Diversity and Inclusion statements. When we demanded you live up to your own creeds, you cowered behind old racist laments of feeling threatened, and then discarded us along with the values you claim to uphold.”

The letter calls for an accounting of the ways in which a White-controlled system has minimized Black work and silenced Black voices, and demands a plan for radical restructuring going forward.

It is accompanied by a call to sign a petition titled “Demand change for BIPOC theatremakers,” now with 80,000 signatories. Together, the manifesto and petition are an example of the broad racial reckoning that has occurred across industries—including sports, media, food, and entertainment.

Addressing “theatres, executive leaders, critics, casting directors, agents, unions, commercial producers, universities and training programs,” the letter states: “You are all a part of this house of cards built on White fragility and supremacy. And this is a house that will not stand. This ends TODAY.”

Press coverage has been widespread, but given that the originators have yet to grant interviews, what's next is not fully clear.

And not every prominent BIPOC artist is on board; though he declined to comment for this article, the Pulitzer Prize-winner, Jackson, posted a tirade on his Facebook page on June 13 that called the letter “stupid, insane, reckless, disgraceful, disgusting, embarrassing, counterproductive” and “Trump-like” among other criticisms, which included profanity. “Theater is supposed to bring people together, and this horrible, horrible letter does nothing but tear people apart.”

In a follow-up, he complained: “There has been no public debate about ‘We See You’ and the seeming total consensus around it.” Both posts have since been deleted.

A Full Accounting

Activists say they want more than provocative rhetoric. They want a total reconstruction of a creative culture system they view as having excluded the voices of Black participants by its very design.

“The reality is that when most of these institutions and theaters were built, when their mission statements were written, Black people and Black voices were not a part of those conversations—not a part of the building, not a part of the infrastructure,” says Marie Cisco, a producer of shows that include Ain’t No Mo’, Black Girl Magic, and Folk Tales. “The only way for us to create equity is for us to be part of the foundation of the future.”

Cisco argues for programs that prioritize racial equity. Everything from staff-wide diversity training to building more theaters in minority communities is on the table. There are a lot of possible avenues to repair what she sees as flaws in the system, but she doesn’t think it’s necessarily the responsibility of activists such as her to think of all of them. “We’re done spoonfeeding White people information—behaviors, decisions, language, history, propriety,” she says. “We’re done making it easy for them, done making them comfortable.”

As a first step, Cisco has put together a nationwide Theaters Not Speaking Out list, a public spreadsheet that keeps track of theaters’ responses to the Black Lives Matter movement. In the past few weeks, only a portion have spoken up about systemic racism, even though it is an issue that has occupied their stages—and been core to some of the most lauded works in American theater.

And, Cisco says, the recent empathy has often come only after prodding, or is cagey at best. Her spreadsheet has a column for responses that don’t explicitly say “Black lives matter,” for example.

The Statistics

Although the nation as a whole is 76.5% White, Cisco’s spreadsheet flags the racial composition of each theater’s city, to show the racial disparity between the region at large and the makeup of theater boards and staff. By this logic, she says, all-White leadership is more problematic in Atlanta, which is 51% Black, than in Boise, which is 89% White. The Kimmel Center for the Performing Arts, for example, has a board that is 21% Black even though it’s in Philadelphia, which is 44% Black.

Mary McColl, executive director of Actors’ Equity Association, sees these disparities and has pledged to work toward change. “I’m determined to think of this as an opportunity,” she says. “We have this great chance to dismantle the standard, the standard that has been built on White privilege and White supremacy.”

McColl and the rest of Equity leadership are aware that the first steps can start in their own backyard: The 50,920 members of Actor’s Equity are 7.5% Black, 2.5% Latino, and 2.2% Asian. Its national council is overwhelmingly White, and its foundation board is entirely White. On June 18, the organization’s national council released a resolution pledging to address systemic racism on many fronts, from making it easier to become an Equity member, to changing the face of Equity leadership, to negotiating on behalf of members to enact change in workplaces.

A seven-year analysis by the Asian American Performers Action Coalition (AAPAC) regarding the distribution of Broadway roles by race found that White actors routinely hold roughly 80% of roles; the same analysis found that only about 10% of roles are cast nontraditionally, defined by Equity as “the casting of ethnic, minority and female actors in roles where race, ethnicity or sex is not germane to character or play development.”

A similar three-year study by Equity found comparable data and added that the same biases are seen backstage, where, for example, 77% of stage manager contracts went to White people on Broadway and 83% to White people at Off-Broadway productions. A separate diversity report by Aapac found that 95% of Broadway’s writers and directors are White.

But Broadway has some surprising data as well. Women of color in musical principal or chorus roles report higher average minimum salaries than either women or men as a whole. And the most celebrated actor in Tony Awards history, with six wins, is Audra McDonald, a Black woman.

With New Systems, New Leaders

Stacey Rose and Keelay Gipson, both playwrights, have been assembling Theatre Makers of Color Requirements, an open survey with the goal of gathering cohesive industry demands. One suggestion was for equity-focused ratings or rankings for theaters, along the line of restaurant scores or hotel stars.

Rose says the immediate future needs “constitutional-level specificity” in new language. Something that may seem minor from outside the theater world, such as contractual racial equity in hair styling, for example, can impact large numbers of people significantly. (Productions often don’t provide stylists who are familiar with Black hair, which means that African-American performers have to do their own styling, pay out of pocket, or risk damage at their stylists’ hands.)

In an example of an attempt at such specific accounting, in 2018, the Public Theater in Manhattan set goals for 2023 that the full-time staff would not be more than half male or more than half White “at all levels of the institution”—and that the board would “better represent the demographics of New York City” by being at least 35% non-White. (The city is 57.3% non-White).

But such approaches are, as Cisco puts it, “metric” and often doomed: “When you slap a number on it, that’s when you get in trouble. The numbers are up, but they aren’t bringing to the table what you need. You have to clean house, not just bring in percentages.”

Cisco suggests considering budget decisions such as pay parity across gender and race, or paid internships and apprenticeships (unmentioned in the Public’s seven-point plan). Shareeza Bhola, the Public’s director of institutional communication, declined to elaborate on its diversity goals.

The View From the Audience

As a business and as a creative practice, Broadway steadily serves a predominantly White audience of domestic female tourists. In the 2018-19 season, when Broadway enjoyed an all-time high of 14.8 million show admissions and a total box office gross of $1.8 billion, 74% of theatergoers were White. The most typical theatergoer was a White, college-educated woman in her early 40s, from a household with an average annual income of $261,000, who paid, on average, $145.60 per ticket.

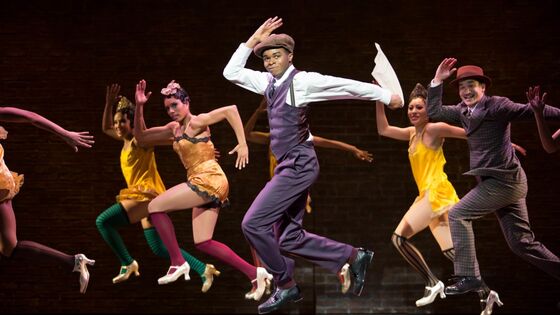

And Black-centered productions that aren’t jukebox musicals tend to be fleeting. Shuffle Along, a star-studded show about an all-Black 1921 musical that broke records by running for 484 days, ran for 131 days in 2016. Choir Boy, the Broadway debut from Moonlight writer Tarell Alvin McCraney, showed for 88 days. The Pulitzer Prize-winning A Strange Loop ran for 65 days Off-Broadway. An Off-Broadway revival of By The Way, Meet Vera Stark, by two-time Pulitzer winner Lynn Nottage, ran for 40 days last year. And in 2017, School Girls; Or, the African Mean Girls Play ran just 25 days.

The most reliable Broadway production for Black actors in the 21st century has been The Lion King, a musical about African animals that has so far grossed $1.7 billion and is the most profitable musical of all time.

Many modern success stories of Black-centered theater—such as 1996’s Ragtime, 2003’s Caroline or Change, 2005’s The Color Purple, 2010’s The Scottsboro Boys, or 2018’s To Kill A Mockingbird—feature segregation as a core issue. “Those plays tend to be the ones pulled forward by White institutions. We call it poverty porn. That’s what we see White audiences like,” says Keith Josef Adkins, a playwright who is artistic director of the New Black Fest. “They like when all of us are poor or struggling.”

Producers must ask themselves, “‘Are we making choices based on the comfort and fragility of White audiences?’” Adkins continues.

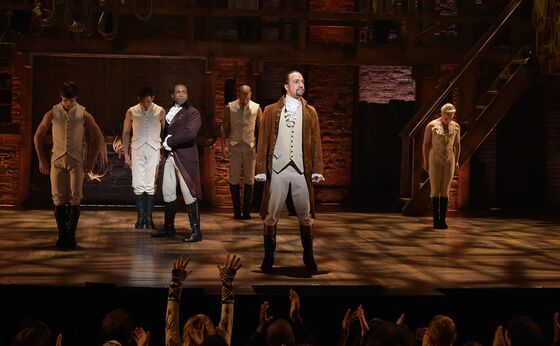

Even Hamilton erased slavery, highlighting slaves owned by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, the musical’s villains, but ignoring those owned by Alexander Hamilton, Eliza Schuyler, or George Washington, the play’s heroes. “That will expose how some plays by people of color—and Black people, in particular—are reshaped or reengineered to fit the comfort of those audiences.”

How It Happens Backstage

Brandon Nase, who founded Broadway for Racial Justice on June 1, says such comportment begins in university programs. “You go into a voice lesson, and you’re a Black person, and they’re like, ‘Oh, here’s Make Them Hear You,’” he says, referring to a song from Ragtime about racial injustice. “Whatever color you are, here’s where you fit into the industry. You’re bred into that for four years.”

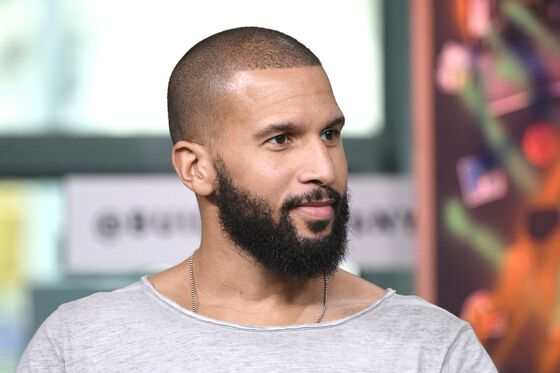

Sydney James Harcourt leaped from Hamilton, where he understudied for Aaron Burr, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington, to Girl From The North Country, where critics showered him with praise and he scored several award nominations. And yet, “I have to, at all times, guard myself and not make missteps because of being a Black male,” he says. “I’m Black, and to ask for anything is considered being difficult. Things that White actors can do naturally and are kidded about—this actor talks so much, this actor is always late—that becomes something you will not be hired back for when you’re a Black actor, no matter your reviews or the awards you’re nominated for.”

As a result, Harcourt says he is not optimistic about change. “If you blink the wrong way, they will replace you because they can get another Black actor,” he says. “And they do.”

Means of Redress

With Broadway for Racial Justice, Nase is creating theater partnerships and a hotline separate from the one run by Equity because, he explains, “We are literally sitting here telling you the system you have in place doesn’t work, it’s not worked, never worked.” The way of receiving and addressing complaints has to be broken down and rebuilt, he argues. “You’re going to send an email that says, utilize this system if you’re experiencing [racism],” he says of Equity’s options. “It’s insane. It’s literally saying: ‘Are you being attacked by the police right now? Call 911.’”

Callers “won’t have to break down how a situation is racist,” he explains. And once logged, complaints might be more sufficiently addressed, thanks to the theater partnerships.

Heather Hitchens, president of the American Theatre Wing, whose board is 68% White and whose advisory committee is 81% White, agrees that radical change is needed. “We were founded by suffragettes, and we think of those badass women and how they’d be reacting to all this,” she says. (ATW is an education nonprofit that runs the Tony Awards in partnership with the Broadway League; its board chair, David Henry Hwang, is a We See You signatory.)

Hitchens has focused on things over which she has direct control: board members, the advisory committee, and Tony nominators. Anti-racist strategy, she says, “needs to be integrated as a principle, not a program.”

She points to ATW’s SpringboardNYC initiative as an example of a new system aimed at rectifying imbalances. A mentoring program tied to the Tonys that is 68% non-White, it gives students a leg up in the industry. Also, in June 2019, ATW’s board instituted a new policy of forced attrition that any advisory committee member who has served three consecutive three-year terms is required to take a year off, without the promise of return. (The rule was scheduled to go into effect this month, but has been delayed by the pandemic until June 2021).

When asked if ATW would consider requiring Tony nominees to meet diversity requirements, as the Academy Awards is attempting to do, Hitchens says “every possible path to equity is on the table.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.