How Wind and Solar Power Got the Best of the Pandemic

How Wind and Solar Power Got the Best of the Pandemic

(Bloomberg) --

Global recessions, wars, and (yes) pandemics have a way of driving down energy demand. Last year, the International Energy Agency said the collapse in global primary energy demand brought on by Covid-19 was the biggest drop since the end of World War II, itself the biggest drop since the influenza pandemic after World War I.

Something was different about this collapse, though, something that is not only unprecedented but until recently impossible in global energy. As the IEA’s latest data shows, renewable energy grew last year, and it was the only energy source that did so as consumption of gas, oil, and coal all declined. Renewables were not just an energy growth sector; they were the only energy growth sector.

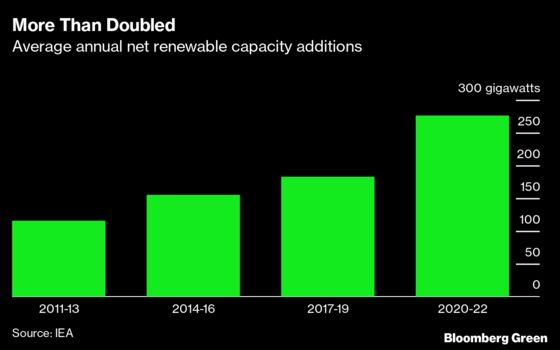

Not only did renewable energy grow, it did so in record fashion. The IEA’s latest data confirms something my colleagues and I have been observing since the end of 2020: renewable energy installations not only increased during the pandemic, they exceeded even the most bullish of expectations, with wind installations increasing 90% and solar increasing 23%. The IEA only expects more this year – as it says, “Exceptionally high capacity additions become the ‘new normal’ in 2021 and 2022, with renewables accounting for 90% of new power capacity expansion globally.”

That last figure is quite something. Renewable energy has received the majority of all money invested in power generation for years, and it has accounted for the majority of all capacity additions for some time too. But “majority of” and “90% of” are rather different.

I say that because a scale tipped so far in the renewables direction takes more than just electrons with it. It takes capital along, too. Of course it means physical capital, in the form of power generation assets, but it is also means financial capital. And with 90% of all capacity additions coming from renewables, that also means that most of the asset financing in the electricity sector is going to renewable energy, too. Combine the physical and financial capital, and there’s another capital to consider—human capital. Human capital is a virtuous cycle: the more familiar people and institutions become with renewable energy, the more that they are interested in financing more of it, the more expertise they create, and the more opportunities they unlock.

Seasoned energy observers will note that the coal sector, in particular, has long had a dedicated set of investors. Regardless of a general tilt towards renewable power generation additions, some major financial institutions have stuck to their investment theses in fossil-fueled power. The Asian Development Bank, in particular, has maintained the importance of coal-fired power as a way to address Asia’s energy access needs. But even that is beginning to change.

Earlier this month, the ADB quietly published a draft version of its updated energy policy. It proposes to cease financing almost all fossil fuel-related activities, with only a few carve-outs for transitioning plants to use cleaner fuels:

It is now coal – and perhaps even natural gas, if positions like the ADB’s continue to hold – that is on the back foot for global energy investment.

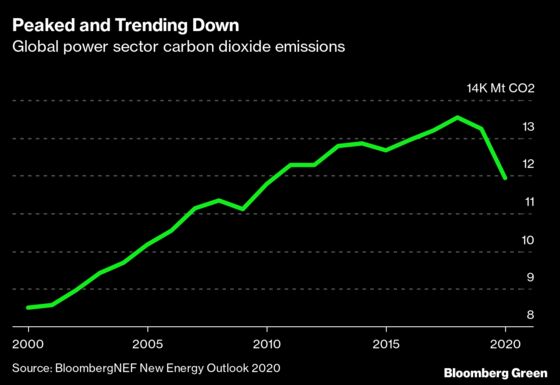

The most consequential impact of last year’s renewable energy build-out was that it cemented a trend that began with another extraordinary milestone in the world’s electricity system. That is the peak in power sector emissions, which happened in 2018.

BloombergNEF does not expect power sector emissions to ever recover to their peak in 2018, and another few massive years will only further this trend. With technology, capital, and expertise on the side of renewable power, the only question about the future shape of that curve is how far down it goes, and how fast it gets there.

Nathaniel Bullard is BloombergNEF's Chief Content Officer.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.