How to Make Sense of Russia’s Contradictory Oil Data

How to Make Sense of Russia’s Contradictory Oil Data

(Bloomberg) -- Data on Russia’s oil industry can be downright confusing.

The country has been entangled in a web of restrictions since the invasion of Ukraine, from outright import bans to shipping problems and buyers’ strikes. The real impact of these overlapping measures is hard to gauge, with key statistics pointing in different directions.

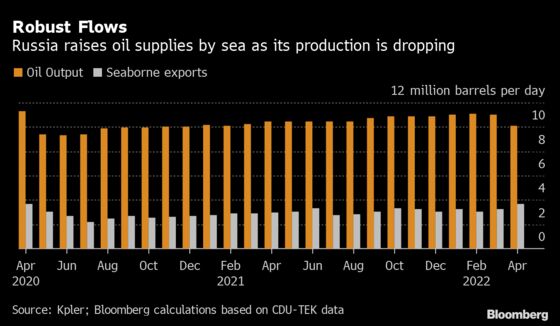

This month, Russia’s daily average seaborne oil flows are set to jump by some 450,000 barrels from March, reaching a three-year high of 3.67 million barrels a day, according to estimates from market intelligence firm Kpler. At the same time, the nation’s production dropped by more than 900,000 barrels a day, down to levels last seen in early 2021.

If Russia is pumping less oil, how is it able to export more? The answer lies in the facilities that process crude into fuels.

“The April hike in exports is largely attributed to lower refinery runs,” said Viktor Katona, head of sour-crude analysis at Kpler.

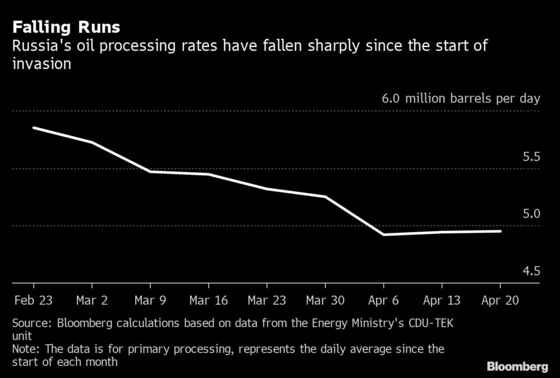

While Russian daily oil production so far in April has been about 8.8% below pre-invasion levels, the amount of crude processed by refineries has slumped 15.3%, according to data from the Energy Ministry’s CDU-TEK unit seen by Bloomberg.

Oil that’s no longer processed by Russian refiners has to go somewhere. Initially it was put into temporary storage at the oil fields as producers were sought new customers. Now it’s being sent for export, resulting in rising shipments of crude grades like the Siberian Light blend from Russia’s Black Sea coast, according to Jay Maroo, lead crude analyst at Vortexa Ltd.

Lost Market

Russia’s oil industry accounts for roughly 10% of the global crude output and is the single-largest source of money for the nation’s budget. It has faced an unprecedented squeeze in the past months as western countries and their partners try to end the war in Ukraine by curbing the Kremlin’s revenues.

Some countries, notably the U.S., have announced outright bans on imports of Russian fuel. It was this move by the White House that made Russian refineries one of the the first victims of sanctions.

American refineries were major buyers of Russian fuel oil because they had specialized equipment that could turn it into gasoline. Finding another market after the ban came into force proved nearly impossible and stockpiles of the heavy oil quickly began to pile up, forcing some Russian refiners to shut-in their operations.

As broader sanctions hit Russia’s economy, the domestic market for refined oil products is also shrinking.

“Car owners are driving less compared to what was considered normal in the pre-crisis times because of declining real incomes or growing risks of such declines,” Moscow-based consultant Petromarket said in its latest report. “Demand for gasoline is negatively affected by emigration, unemployment, forced holidays or a switch to work from home for a large number of Russians as many foreign companies quit Russia.”

Russian refiners sell nearly all of the gasoline they produce in their home market, where price signals suggest a growing supply surplus, according to Petromarket. As of April 26, deliveries of gasoline to the domestic fuel exchange increased by 5% compared to March, yet the average prices for different types of the fuel dropped 8%-10%, according to the consultant.

Russian refineries’ throughput does typically drop at this time of year due to seasonal maintenance, but that doesn’t explain the full extent of what’s happening, said Katona. There are signs that some facilities may not restart on the usual schedule after maintenance.

Idle Plants

As of April 18, only 23 out of 106 Russian refinery units that went offline were going through planned maintenance or planned repairs, and 10 were on unplanned repairs, with 14 more undergoing overhaul maintenance, according to data from Moscow-based Commodities Markets Analytics. Another 29 had simply been idled and 7 were in hot circulation, the data showed.

Idling typically happens when a plant is taken offline for non-mechanical reasons such as unprofitable margins or a lack of demand for the processed fuels. Hot circulation means that the refinery isn’t producing any fuel, but continues performing basic processing in a loop so it could be restarted promptly if needed.

“The maintenance season is supposed to be gradually over in May yet we are not expecting a visible short-term recovery in Russian processing volumes,” Katona said.

This would mean additional volumes of crude being diverted to export. Kpler expects Russia’s May seaborne oil shipments to be only marginally lower than in April, even if the country’s crude production keeps falling.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Bloomberg