Why I Want to Wander Through Brazil’s Wild Outdoor Art Museum

Why I Want to Wander Through Brazil’s Wild Outdoor Art Museum

(Bloomberg) -- Here at Bloomberg Pursuits, we know most of your plans are on hold. Ours are, too! But that doesn’t mean we’re not daydreaming about the trips, meals, and other worldly delights that we’ll rush out to experience once it’s safe again to do so. We’re sharing our ideas with you in the hopes that they will help inspire you—and we’d love to hear what you’re daydreaming about, too. Send us your thoughts and plans at daydreams@bloomberg.net, and we’ll flesh some of them out for you in future versions of this column so we can help you make them a reality.

Homebound the past few weeks, what I miss is pretty straightforward: I want to see friends again, go to galleries, visit my favorite Mexican restaurant. But every so often I find myself lingering on more grandiose possibilities, topmost of which is a trip to Inhotim, a 250-acre sculpture park about an hour and a half’s drive from Belo Horizonte, Brazil.

Full disclosure: I’m partially motivated by regret. As the Bloomberg Pursuits arts writer, I get to travel a lot for my job, and while far-flung art fairs and biennials can be eye-opening, I find that at these events I spend more time with the so-called art world than the art itself. That was one of the reasons I pitched a straightforward piece on Brazil’s art scene—no mention of commerce needed.

I truly could not believe my good fortune when the pitch was accepted, and then … I repeatedly screwed up my visit.

After a 13½-hour flight from New York to Rio de Janeiro and an hourlong connecting flight to Belo Horizonte, I picked up my compact rental car—a Volkswagen Gol whose clutch seemed to have worn out in the late 1990s—and drove for two and a half hours. And yes, I know I just said the drive is supposed to be an hour shorter. I got lost.

By the time I got to the park it was almost midday, leaving five hours until it closed. With the benefit of hindsight, after 18 hours of travel I might have taken a few deep breaths, or maybe sat down for five minutes to eat a sandwich. Anything to regain my equilibrium before setting out to visit a place that had, since its opening in 2006, been at the top of my bucket list.

Instead, I started out at a frenzied half walk, half jog down the park’s manicured paths.

Even with a full day I couldn’t have seen it all, because Inhotim isn’t laid out rationally. (The park is named after a reserve of the same name; “no one knows for sure where the name Inhotim comes from,” the park’s website tells us.)

Instead, it grew organically alongside the ambitions and finances of its founder, Bernardo Paz. Initially, he built a few galleries near his hacienda; then he added one sculpture, then another, and then another. Aided by the art adviser Allan Schwartzman, Paz began to fill out the park in earnest over the course of about a decade. Along with dozens of sculptures, Inhotim includes more than 16 major pavilions, many of which feature single-artist commissions.

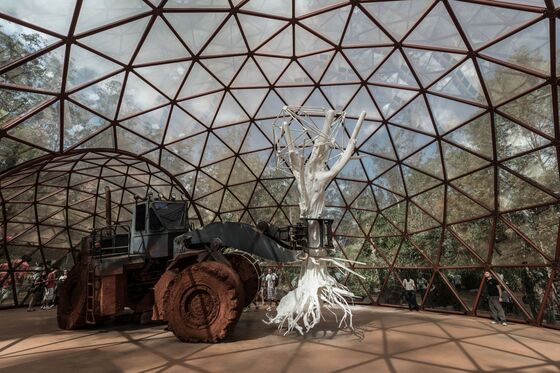

I was not, I soon discovered, in a position to give each pavilion the time it deserved. I stuck my head inside a geodesic dome built by Matthew Barney that contained an industrial skidder, a vehicle used for dragging cut trees, which in this instance was holding one of Barney’s sculptures. Then I left. I admired a glass building built by Doug Aitkin that makes sounds based on reverberations from a 663-foot-deep hole drilled into the earth, and then moved on. I’m not sure I even stopped in front of a 32-foot-high bronze tree, seemingly suspended in the air by the Italian artist Giuseppe Penone.

And did I mention that Inhotim is also a botanical garden with more than 4,200 species of plants? I can assure you, I did not spend much time on flora.

Despite my rush, I did have the presence of mind to realize where I was. Inhotim is a kind of eden, a sparsely attended, well-staffed paradise that makes a compelling case for the longevity of contemporary art. It was living, breathing proof that good art can hold its own outside the confines of a white-walled gallery. Maybe it was the jet lag, maybe it was the fact that I hadn’t eaten for a while, but the experience gave me a rush I haven’t had since.

Beyond regret, that’s the main reason I’m so desperate to go back. Every artwork I see today is on my computer screen; Inhotim wasn’t just art in person. It was art in the wild—the best of all my worlds.

How to Get There, Where to Stay, and What to Do

When I return, I plan to make more of an occasion out of it.

First, I’ll be sure to rent the right car. I’m loath to ever recommend that anyone rent or drive an SUV, but given how many times I scraped the bottom of my first rental car on bumps and potholes, in this case I might make an exception. There’s a Hertz at the Belo Horizonte airport that offers the Jeep Renegade, a compact crossover with 8 inches of ground clearance, which you can rent for $50 a day. Go for it.

When it comes to places to stay there are several options, all of them reasonable, none of them dazzling. I stayed at what Booking.com had said was the third-best five-star hotel in the city, the Royal Savassi Boutique Hotel, which cost about $60 a night for a standard room. It was totally pleasant and well-located; that said, next time I’d probably try somewhere else.

The Hotel Fasano Belo Horizonte is about three times as expensive—rooms start at $180 a night—but this is a daydream, which means I can pretend I have the disposable income to spend as much as I want, and the rooms look like a definite step up.

As for food, a friend took me around to his favorite places, and I’d go back to every one. Xapuri isn’t exactly a hidden gem, but the food—local cuisine such as frango com quiabo, a chicken stew with okra—was unbeatable. Similarly, I discovered only after eating at Cantina do Lucas that it’s included in basically every tourist guide; that didn’t stop me from having a delicious meal. And for what it’s worth, I didn’t hear a word of English spoken.

Most important, if anyone makes the effort to visit Belo Horizonte from the U.S., hopefully they’ll take time to explore.

The same week I visited Inhotim, I traveled to possibly the most surreal place I’ve ever been in my life—a baroque, hillside city called Ouro Preto, which was built on the edge of a gold mine (and on the backs of the slaves who worked in it). The city is about a two-hour drive from Belo Horizonte, and a visit can easily occupy a full day.

It was one of those places I arrived at and wondered, momentarily, if I was hallucinating. The town is covered in white stucco and adorned with an almost indecent profusion of vivid, flowering plants. Ornate cathedrals, many of which took centuries to build and are covered in literally thousands of pounds of gold, dot the hills, each more elaborate than the next. Much like Inhotim, it was a city that was both of this world and yet totally outside of it—a world that’s perfect for idle daydreams.

Footnote

In the meantime, I’m mostly preoccupied with what’s going on back at home. I’m spending imaginary money on a trip to Brazil and donating real currency to Meals on Wheels, which is currently doing heroic things to get homebound, at-risk seniors the food they need to stay alive.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.