How One of Brazil’s Largest Favelas Confronts Coronavirus

How One of Brazil’s Largest Favelas Confronts Coronavirus

(Bloomberg) -- The onset of the coronavirus pandemic in Brazil’s favelas, shantytowns that sprawl around the country’s largest cities, has left the 11.4 million Brazilians living in these densely-populated neighborhoods in a particularly vulnerable position.

In addition to their usual problems -- violent shootouts, open sewage, military-style police operations against drug traffickers -- they now struggle to embrace social distancing guidelines while living side-by-side in haphazard constructions and crowded homes.

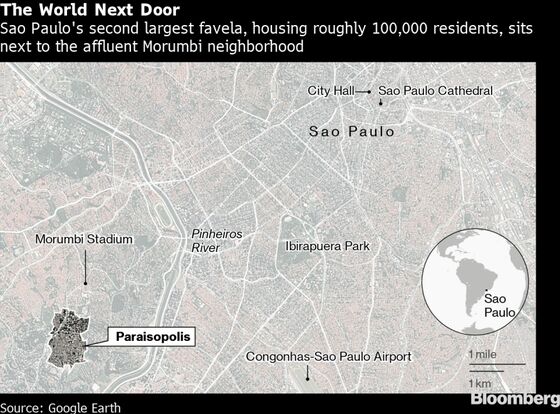

Yet residents of Paraisopolis, Sao Paulo’s second-largest favela, have come up with a plan to combat the coronavirus with little government help.

Their campaign involves a number of actions made possible by donations and volunteer work, from 10,000 free meals to private ambulances to a grid system of volunteer “street presidents,” who check to make sure everyone on their street is OK. They have dedicated one building as a quarantine house, and they are turning closed schools into centers where residents who are unable to self-isolate can come to sleep.

Those who lost their jobs as housekeepers for rich Sao Paulo residents can apply for an “Adopt-a-Housekeeper” program, through which they can receive 300 reais ($55) paid by a crowd-funding project.

Gilson Rodrigues, who leads the residents’ union in Paraisopolis, hopes other favelas can follow their lead. “The idea is to replicate these activities in other communities,” he said, “and to serve as a model that can be applied in other places.”

With the peak of the pandemic still to come in Brazil, it’s not clear how successful their strategy will be to slow the spread of the virus in their community. The state of Sao Paulo is the hardest hit by Covid-19, with over 30,000 cases and 2,511 deaths as of Friday, most of them in its capital city. Yet President Jair Bolsonaro continues to urge Brazilians to resume work and businesses to reopen, harshly criticizing the restrictive policies of Sao Paulo Governor Joao Doria.

What makes social distancing nearly impossible in favelas is the combination of crowded spaces, poverty, and little government support. Over 100,000 Brazilians live in approximately 21,000 homes in the 800,000 square-meter (0.3 square miles) neighborhood of Paraisopolis. Multiple generations of a family often share the same small living space, and research has found that someone living in favela-like conditions spends 50% more time per day in contact with others than those living in richer areas.

A 2018 study published in the peer-reviewed academic journal BMJ Open on the spread of influenza in slums in India found that they “sustain greater infection rates than non-slums under all intervention scenarios, sometimes by as much as 44.0%” due to the greater household sizes.

It’s unclear what Brazilian shantytowns in particular may experience during Covid-19’s outbreak, though, because “there is no model for how the virus spreads through favelas,” said biologist Atila Iamarino, who specializes in viruses.

Paraisopolis abuts one of the city’s wealthiest enclaves -- Morumbi -- resulting in dramatic images of Brazil’s economic inequality, as corrugated tin roofs contrast with bright white 30-story apartment buildings with sparkling pools.

“It’s a big challenge for residents in favelas to deal with the pandemic,” said Rene Silva, founder of the nonprofit news organization Voz das Communidades, which is based in Rio de Janeiro. “You might only have two or three rooms, but five or six people living together.”

His group and others are racing to come up with innovative ways to face the crisis, but the challenges are significant. “People keep circulating in the streets because they have to get the money they need to buy food,” he said. “And the small businesses in the community, even if they aren’t considered essential, have salaries and bills to pay, so they prefer to stay open.”

On a recent Thursday, the main commercial streets of Paraisopolis were busy with people and motorcycles. Some of the residents wore masks, but most did not. Most shops were open, and commerce was as busy as usual. Many now have another reason to leave their house: a 600 real ($115) stimulus check is on the way from the federal government. Accessing the money they need so badly may pose yet another health challenge as communities report hours-long lines to retrieve the payment.

“I am waiting,” said 24-year-old kitchen assistant Larissa Silva. “When I receive it I will pay my debts and buy food.”

The Sao Paulo city government said it’s distributing food donations among families living in precarious situations, including those in Paraisopolis, while also working to disinfect the streets. It didn’t have an exact figure for the number of Covid-19 cases in Paraisopolis, offering instead numbers for the larger region where the favela is situated.

But the residents’ union has been creating their own unofficial tally. Francisca Rodrigues, vice-president of the union, who is unrelated to Gilson, said that as of Thursday they counted 64 cases in the community. They haven’t counted any confirmed cases of deaths from the virus.

“But these were just the cases reported by the doctors working for the ambulance system we have set up here in the favela,” she said. “There must be many more cases in Paraisopolis.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.