How Exxon’s Climate Change Trial Became a Battle Over Numbers

How Exxon’s Climate Change Trial Became a Battle Over Numbers

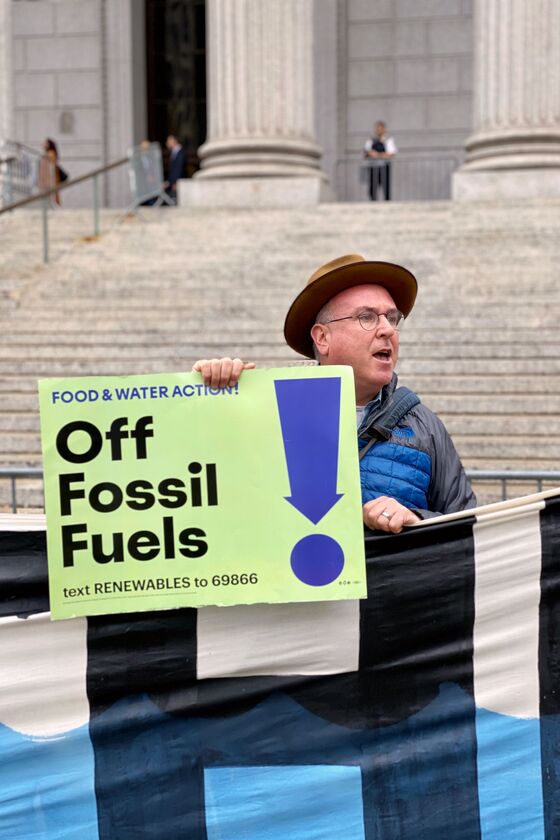

(Bloomberg) -- Climate change protesters outside a Manhattan courthouse this week expressed overwhelming support for New York’s landmark securities fraud lawsuit against Exxon Mobil, even if they weren’t entirely sure what the case was actually about.

Several participants at a rally on the first day of a three-week trial said they believed the litigation had been brought by the office of New York Attorney General Letitia James to hold Exxon accountable for its role in climate change.

“My understanding is New York State is suing Exxon so they will be financially responsible for creating climate change—the same way opioid manufacturers and distributors are being held accountable,” said Sandra Termini, a 68-year-old retired computer software engineer.

But as we explained in our preview of the trial in New York State Supreme Court, what was originally advertised as a frontal assault on Big Oil for fueling the planetary climate crisis has—over the years—been transformed into the kind of hair-hurting corporate accounting lawsuit more common to the courthouses just a few subway stops north of Wall Street.

The trial is over Exxon’s use of a “proxy cost” for carbon in its annual calculations predicting global energy demand, and its use of a greenhouse gas (GHG) metric for gauging expected climate taxes on specific projects. Such figures are used by fossil fuel companies to assure investors and regulators that they’re incorporating additional costs they may face in the future, and the potential decrease in value of untapped reserves as the world weans itself from fossil fuels.

Not exactly the final word on who is most at fault for global warming. So how did this happen? How did New York’s legal broadsword turn into a scalpel?

Back in late 2015, when then-New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman announced his unprecedented investigation of Exxon, he sold it as a general attack on one of the alleged perpetrators of climate change. He said he wanted to find out if Exxon and other oil companies hid early knowledge of fossil fuel’s role in global warming and then tried to undermine climate science—allegations laid out in reporting by two news organizations. The energy giant has denied any such wrongdoing.

Proving the explosive claims turned out to be harder than Schneiderman thought. After years of legal battles with Exxon, which fought the investigation at every step, the attorney general’s office was left with a very different case to make.

By June 2017, New York’s probe had become about how Exxon misrepresented the cost of climate change to its business, using two sets of numbers, one public and one private. The oil company rejected the new argument and seized on the shift in legal strategy, attempting unsuccessfully to use it as a reason to have the lawsuit dismissed.

Since the New York investigation was announced, the oil company organized a massive legal response, suing to block parallel probes by New York and Massachusetts on the grounds that they were politically motivated and collusive. The effort failed.

“Investigations shift all the time,” U.S. District Judge Valerie Caproni told Exxon lawyer Justin Anderson during a hearing in November 2017. “If that gives rise to federal-court proceedings, then the world of federal investigations will come to a halt.”

But when New York state finally got its hands on some 4 million pages of documents, they weren’t enough to make the bigger case: that Exxon lied about climate science or the future value of its yet untapped assets.

On Tuesday, outside the Manhattan courthouse, this didn’t seem to bother the protesters. Termini, the retired software engineer, wouldn’t budge on the importance of the case and the need to show support for an environment under threat from the burning of fossil fuels.

“This is just fine,” she said of the securities fraud case. “Whatever works. Climate change is so huge—whatever we can do.”

Gail Buckland, a 71-year-old author, curator and college professor at The Cooper Union, also expressed a broad view of the litigation. She held a sign reading: “Exxon defrauded us all.”

“Exxon is one of the biggest problems we have on the planet,” Buckland said. She said she joined the protest “to be able to address the corporation and their dishonesty and their huge profits at the expense of my grandchildren and everyone’s future generations.”

Eric Weltman, a Brooklyn-based organizer with the group Food & Water Action, said New York is holding Exxon accountable and “making them pay for literally decades and decades of knowingly polluting our planet, threatening our climate, and frankly—you know—risking life on this Earth.”

Exxon spokesman Scott Silvestri responded to the protesters by saying the company has invested about $10 billion in projects including biofuels, flare reduction and carbon capture and storage. Though Exxon lawyer Anderson said during the 2017 court hearing that Schneiderman’s investigation was based on climate change “alarmism,” Silvestri said Exxon now believes that “climate change risks warrant action.”

“We’re focused on reducing our emissions, helping consumers reduce their emissions, conducting breakthrough research into lower-emissions technologies, and supporting public policy, such as a uniform cost of carbon, to reduce emissions at the lowest cost to society,” Silvestri said in a statement.

Buckland, the professor and curator, said she thinks Exxon’s claims are dubious.

“When they stop drilling oil, I will believe it,” she said.

Dan Abbasi, managing director of private equity firm GameChange Capital and a longtime advocate of tackling climate change, said the unusual trial is a good start for addressing the crisis.

“The executive and legislative branches have largely abdicated their responsibility; that leaves the judiciary,” he said. “The legal process is based on the discipline of evidence, and the evidence is extremely strong on climate change.”

Public sentiment notwithstanding, Big Oil has been trying to move the growing number of state court lawsuits to more friendly federal court venues. Unlike New York, most climate change cases filed by local governments and another state, Rhode Island, cite nuisance laws aimed at punishing companies on behalf of taxpayers, rather than investors.

On Oct. 22, the U.S. Supreme Court handed energy companies another defeat, letting government officials press ahead with three lawsuits that accuse more than a dozen oil and gas companies of contributing to the climate crisis.

The court refused to block a lawsuit by Baltimore as companies try to shift it from Maryland state court into federal court. Individual justices then rejected similar requests in cases from Rhode Island and Colorado.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: David Rovella at drovella@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.