How Dealmaking Has Changed in the Decade Since the Crisis

How Dealmaking Has Changed in the Decade Since the Crisis

(Bloomberg) -- A decade after the financial crisis scotched M&A activity along with much of the economy, dealmaking could be poised to reach unprecedented levels as it wraps up the fifth year of a rebound, despite an increasingly fraught backdrop.

Global transactions reached $3 trillion even before the start of the fourth quarter, topping every year since the millennium began except 2007, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. In each of the past three years, the final quarter has been the most active of all, meaning 2007’s $4.1 trillion milestone may be left behind by year’s end.

To mark 10 years since the collapse of Lehman Brothers heralded the unofficial start of the crisis, Bloomberg Deals looked back over a decade of data to see how dealmaking has changed. Where’s the money flowing, will big leveraged buyouts ever come back and do escalating trade tensions mean we’ve already passed peak China? Here’s what we found.

Five Years

While dealmaking took a hit for several years after the crisis, by 2013 companies started to open their pocketbooks again -- and they haven’t looked back. So far, this year is on pace to beat the post-crisis highs of 2015, with megadeals such as Takeda Pharmaceutical Co.’s $62 billion acquisition of drugmaker Shire Plc and Cigna Corp.’s $54 billion purchase of Express Scripts Holding Co. leading the way.

“In the aftermath of 2008 it took a good five years for people to start thinking about M&A again,” said Michael Carr, global co-head of mergers and acquisitions at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. “It was 2013 when we entered a new era that started the current environment.”

“Five years later, we are now in a place where shareholders are demanding growth and we’re seeing both horizontal and vertical transactions,” Carr said. “All of which are signs of a strong market.”

Dry Powder

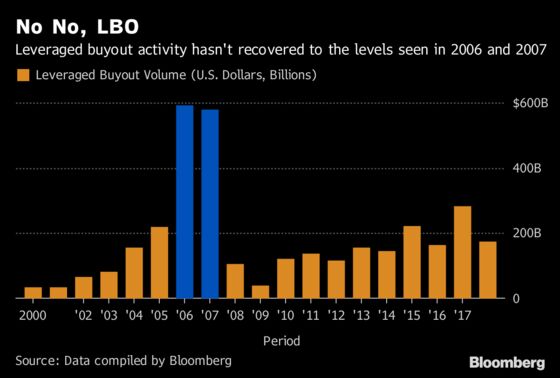

The bounce back has hasn’t been across the board though, with leveraged buyouts still well below their pre-crisis peak. While private equity firms are sitting on more than $1 trillion of dry powder, valuations of potential targets are high and firms are facing increased competition from strategic acquirers for the best assets.

The number of M&A transactions with an enterprise valuation of seven times earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization or more has rebounded since the financial crunch, reaching 432 last year -- about 74 percent of the deals for which the information was available -- according to the data compiled by Bloomberg. The low point was 2012, when about 60 percent of the deals were struck at a multiple of less than seven times ebitda.

Private equity firms’ repertoire has also dramatically broadened in the last decade, with buyout shops now investing in everything from growth-stage companies and real estate to each other.

America First

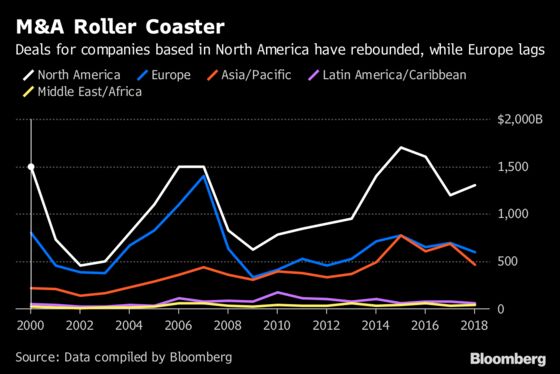

Throughout the slump and the rebound, the U.S. has held its place as ground zero for M&A. Deals to acquire U.S.-based companies account for $1.3 trillion of this year’s completed and pending transactions, out of the almost $2.5 trillion global total, the data show. Four of the top five deals announced in 2018 are for U.S. targets.

It’s a different story in Europe, where economies have been slower to recover and growth has lagged. While U.S. and European companies were almost equally appealing to dealmakers leading up to the crash, acquisitions on the continent have failed to bounce back. Meanwhile, acquisitions involving Asia-based companies have picked up some of the slack. Those deals now make up almost 19 percent of total transactions, compared with 12.6 percent pre-crisis.

Software Rush

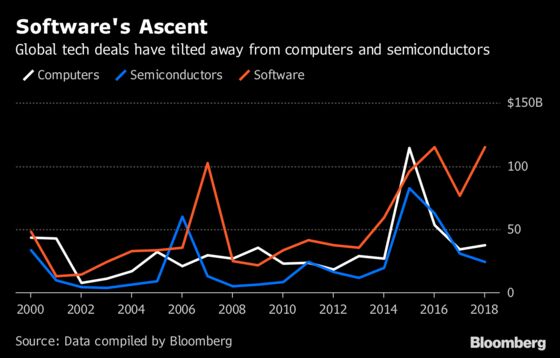

Almost every company can claim it’s a technology asset now, and it shows in the numbers. Deals for tech-focused targets are up 75 percent this year with Broadcom Inc.’s $18 billion acquisition of CA Inc. the biggest of the bunch, the data show.

The San Jose-based company’s chosen target (though let’s not forget it went after Qualcomm Inc. first) reflects a broader trend across the industry, with acquirers favoring software purchases over the semiconductor and computer deals that drove much of the 2015 volume. It’s also an echo of 2007, when the KKR & Co.-led buyout of First Data Corp. propelled software dealmaking to a previous record.

Chipmakers also fall squarely into the category of companies that are increasingly cited as national security concerns when it comes to dealmaking, as trade tensions with countries such as China lead the U.S. to reinforce the measures it will go to to protect proprietary data and assets.

National Champions

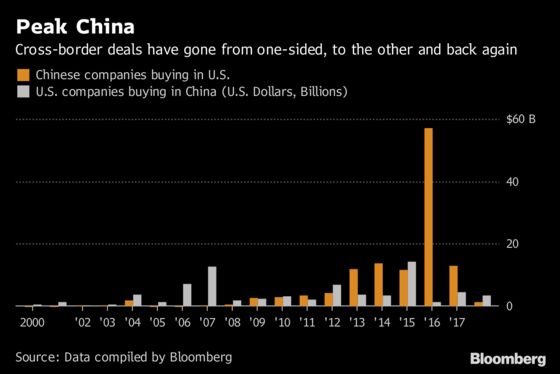

Since President Donald Trump touted Qualcomm’s status as a national champion when blocking Broadcom’s $100 billion-plus bid for the company in March, Congress has granted new powers to the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. to review deals by non-U.S. acquirers.

Though the increased scrutiny isn’t limited to Chinese acquirers, it’s stymied cross-border dealmaking with the U.S. While transactions in which a Chinese company bought a U.S. target climbed steadily in post-crisis years to a startling peak in 2015, activity has been decimated in the past two years as capital controls and a harsher regulatory environment curbed M&A.

The intensifying skepticism -- not just of China but of non-domestic dealmakers in general -- is being felt across the industry.

“The market clearly has slowed,” said Mark Shafir, Citigroup Inc.’s global co-head of M&A, in a television interview, citing a five-month straight decline since March and April, when monthly deal volumes were nearing $500 billion.

Domestic deals among U.S. companies account for $1.1 trillion of dealmaking this year, compared to just $316 billion of transactions in which a foreign acquirer bought an American target, Bloomberg data show.

“If you’re doing significant business in a place like China, just given the state of Chinese-U.S. trade relations, you’ve got to think carefully about how long do you want to be hung up, even if you get a deal announced,” Shafir said.

“You can damage these companies over time if you’re in limbo for two years.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Michael Hytha in San Francisco at mhytha@bloomberg.net;Nabila Ahmed in New York at nahmed54@bloomberg.net;Ed Hammond in New York at ehammond12@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Elizabeth Fournier at efournier5@bloomberg.net, Michael Hytha

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.