How Almost $300 Million Vanished in a Black Hole for Deals in Asia

How Almost $300 Million Vanished in a Black Hole for Deals in Asia

(Bloomberg) -- It’s the black hole of Asian finance: a business with so much gravitational pull that it has swallowed up European and U.S. traders for more than a decade.

The latest victim was France’s Natixis SA, which took a 259 million-euro ($292 million) fourth-quarter hit. The lender found the profits irresistible even after executives got internal warnings that they were taking on too much risk, according to people familiar with the situation who asked not to be named to discuss internal matters.

While the losses are still reverberating at the bank’s Paris headquarters on the Seine, demand for the trade—a security that combines a bond-like coupon with exposure to gains in equities—remains robust. Barclays Plc is hiring the chief Asia salesman of the Natixis deals. Bank of America Corp. and BNP Paribas SA have scooped up some of the remnants of the French bank’s positions, and in so doing they’re ignoring history’s lessons at their own peril, industry veterans say.

“This is a cautionary tale that’s been told quite a few times,” said Clarke Pitts, a former equity-derivatives trader at JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Barclays who wrote a 2013 book about complex financial products. “Natixis sees other firms making money from this and they say we can do that too. The trouble is, that it’s not easy. It’s a bumpy ride, and senior management don’t understand it very well.”

If he didn’t before, Natixis Chief Executive Officer Francois Riahi understands it now. At least two top officials have departed, including Cedric Dubois, the head of Asia equity derivatives, and Nicolas Reille, the salesman headed to Barclays. Groupe BPCE, its parent company, is carrying out an internal review of the debacle. Morale among traders has deteriorated after their 2018 bonuses were shredded in the wake of the losses, according to people familiar with the matter.

Natixis spokesman Benoit Gausseron declined to comment for this story, as did a spokesman for Groupe BPCE. Dubois and Reille also declined to comment.

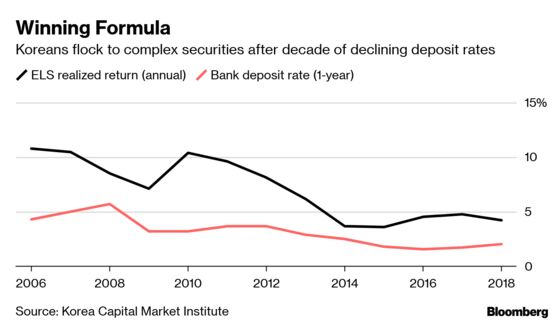

The damage stems from a product originally designed for savers in Japan, where interest rates have been essentially zero for a generation; it has also become a mainstay in South Korea. In the trade, a customer buys an interest-bearing note linked to the performance of shares. The investor only loses money if the underlying equities fall below a preset amount. It’s especially appealing in a bull market, which much of the world’s developed nations have been in for the past decade.

The products—known as “autocallables” and “equity-linked securities,” or ELS—are popular among buyers in their 50s and 60s, who spend anywhere between $300,000 and $2 million on the trades, according to analysts at Samsung Securities Co. and Mirae Asset Daewoo Co. in Seoul. They often expect to make about 8 percent, compared with about 2 percent on South Korea’s 10-year notes; the linked shares sometimes have to plunge by more than half before they lose any principal, analysts said.

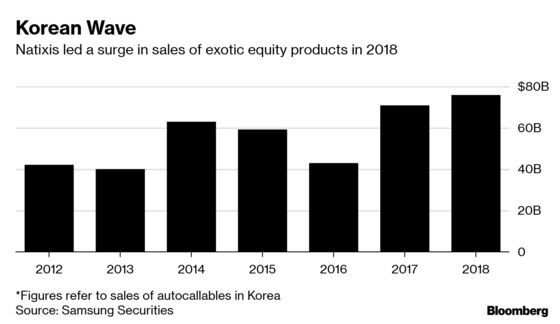

In 2017, when global stock markets surged, lenders including Natixis, BNP and Credit Suisse Group AG sold 81.1 trillion won ($71.7 billion) of the securities in South Korea, a 65 percent increase from the previous year, according to data from Samsung.

“There’s a saying in Korea: there are people who have never invested in ELS, but there’s no one who invested just once,” said Kim Nam-su, a broker at Samsung’s wealth-management unit in Seoul. “That means once you get to know about ELS, you love it.”

For the banks selling them, the complex structures present a multitude of market risks: volatility, currencies and interest rates. In order to protect the value of their autocallable portfolios, banks place offsetting bets, or hedges, which become increasingly complicated and expensive when shares start to decline. Natixis Chief Financial Officer Nathalie Bricker cited “imperfect hedging” for her bank’s losses.

The same problem has tripped up some banks for years. Credit Suisse pushed into the market for Korean derivatives in 2006, only for the gambit to backfire when markets swooned and the bank lost about $120 million, Bloomberg reported at the time.

“The big losses always come from doing too much of a product that cannot be hedged,” said Chris Carter, who was head of equity derivatives at Credit Suisse at the time and now manages a private fund in Park City, Utah.

In 2010, Barclays lost money on Asian autocallables and changed its processes as a result, a person familiar with the matter said. Citigroup Inc. lost more than $50 million on them in 2012, prompting a round of internal rancor at the New York-based bank. ING Groep NV lost a smaller sum around the same time, people familiar with the matter said. In 2015, dealers in the products were burned after Chinese shares traded in Hong Kong plunged.

Credit Suisse maintains a conservative approach to Asian autocallables, according to James Quinn, a spokesman. Spokespeople at BNP, Barclays, ING and Citigroup declined to comment.

Natixis aggressively pushed into this market, creating trades with catchy titles including the Lizard, the Flash Lizard and the Cobra, sometimes offering higher coupons than competitors. The bank structured a product linked to Korean stocks called the Kospi3 and marketed it with a cartoon referencing "Gangnam Style," the global smash hit song named for an upmarket Seoul neighborhood and made famous by the energetic dancing of singer Psy.

South Korea emerged as “a new engine for growth’' and drove “record results’’ for the lender’s equities business across the continent, according to Natixis’s annual reports. The bank reported a 21 percent surge in 2017 equities-trading revenue that surpassed larger Wall Street firms.

Natixis amassed a portfolio of at least $5 billion of autocallables, people familiar with the matter said. In an interview with trade publication Risk.net published Aug. 6, Reille said the Kospi3 product was “disrupting the largest derivatives market in Asia” and he expected volumes to keep growing.

Yet some were already flagging their concerns internally at Natixis, according to people familiar with the matter. Some senior traders advised managers in 2018 that the bank was taking too much risk by building up such a portfolio of esoteric trades, the people said.

In January 2018, amid growing geopolitical instability, Korean stocks ended a two-year climb and began to fall. At Natixis’ Asian headquarters in Hong Kong, problems quickly flared. Yet employees continued structuring new trades, a person familiar with matter said.

By autumn, Natixis dispatched a team from Paris to Asia to assess the situation and subsequently headquarters assumed direct handling of the book, one person familiar with the matter said. Dubois stopped overseeing the book in mid-November, another person said. And on Dec. 18, the bank disclosed the losses, which equaled almost half of its annual equities revenue in 2017, and shares in the bank fell to a two-year low. Natixis has since stopped issuing autocallables in Korea.

“It’s a risky business,’’ said Pitts, the author and former JPMorgan trader. “Most of the time it works well, but from time to time they lose vast amounts.’’

--With assistance from Heejin Kim and Yakob Peterseil.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Hertling at jhertling@bloomberg.net, Sree Vidya Bhaktavatsalam

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.