History Holds Few Lessons If Brexit Means Crashing Out of EU

U.K. officials wondering how to cope with Brexit can generally agree that there’s no precedent for how it might pan out.

(Bloomberg) --

U.K. officials wondering how to cope if Britain crashes out of the European Union can generally agree that there’s no real precedent for how it might pan out.

That’s the theme Bank of England Governor Mark Carney played to when he spoke to lawmakers on Nov. 1 -- exactly one year before he’s set to man the front line defending the post-Brexit economy. “This is rare,” he said. “It doesn’t happen.”

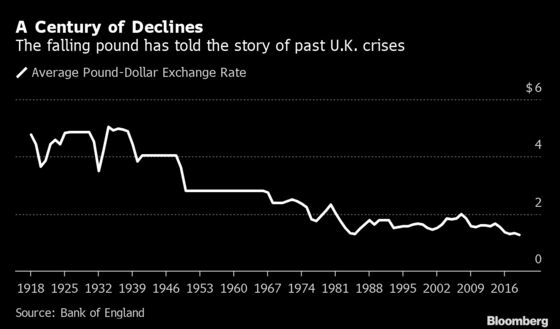

The unique nature of Britain’s challenge if Boris Johnson’s government doesn’t reach a deal with the EU makes the job of finance officials all the tougher, because it forces them to rely on imagination to model complex outcomes as they prepare a response. While the projected slump in the pound has happened regularly in response to past shocks, the same can’t be said for a sudden shutdown in commerce.

“You’re completely re-ordering U.K. trade overnight -- our supply system and the country itself,” said Cathal Kennedy, an economist at RBC Capital Markets and former U.K. Treasury official. “In the context of the economic history we know, post-Second World War, it’s almost unique in stepping back from that, in a pretty dramatic way.”

This lack of precedent is noteworthy in a global economy that has suffered multiple bouts of turbulence. Britain itself has also had its fair share of emergencies since World War II. Here’s a cursory look at some of the U.K.’s previous international economic crises over the years.

Eden’s Emergency

Prime Minister Anthony Eden’s military intervention in Egypt in 1956 to secure the Suez Canal is most often cited as a turning point in Britain’s foreign policy, and showcases a previous attempt by the country to act without wide international support.

Amid the U.S.-led backlash, the country faced a run on sterling. Unwilling to devalue the currency, the U.K. instead sought funds from the International Monetary Fund, helping to establish that institution’s role as an emergency lender.

Wilson’s Woe

Sustaining the pound remained the overarching struggle for policy makers in the ensuing decade and plagued Harold Wilson’s first term as prime minister, starting in 1964.

Britain’s persistent balance-of-payments deficit proved too much to bear however. Three years later, despite Wilson’s efforts to shore up the currency as a status symbol, his administration succumbed to devaluation.

Callaghan’s Capitulation

The country’s economic decline intensified in the next decade. The oil crisis of 1973, rampant inflation, waves of labor strikes and a swelling budget deficit all took their toll, and the pound continued its incessant weakening. By 1976, James Callaghan’s government resorted to seeking what was then the biggest-ever loan extended by the IMF, agreed on condition of budget austerity.

The full facility was never called upon and the episode marked a turning point in the country’s economic policy. And when Margaret Thatcher took power in 1979, she abolished exchange controls.

Major’s Misadventure

Britain’s last significant battle with the foreign-exchange markets was in September 1992. As chancellor of the exchequer during the final weeks of Thatcher’s premiership in 1990, John Major oversaw the U.K.’s accession to Europe’s Exchange Rate Mechanism, a framework for the continent’s currencies as a precursor to the euro.

After Major became prime minister, sterling became a focus of market speculators convinced it was overvalued. That culminated in its exit from the ERM on so-called Black Wednesday -- but not before the Treasury had raised the interest rate to 15% in a failed defense of the currency.

Brown’s Bailout

The British economy faced its gravest moment of the postwar period in 2008. A year of turmoil that had already felled U.K. lender Northern Rock in 2007 and Lehman Brothers that September almost brought down Royal Bank of Scotland and HBOS in early October, requiring a costly bailout by Prime Minister Gordon Brown’s government. The rescue involved the U.K. taking equity stakes in afflicted banks, a model of response that was then repeated elsewhere.

As a consequence, the country’s budget deficit swelled. The next administration, led by David Cameron, enforced a tough austerity program, and cited the need to defend Britain’s longstanding top credit ratings as a justification.

Cameron’s Crisis

The U.K.’s vote in June 2016 to leave the EU prompted the worst daily drop on record for the pound and the resignation of Cameron. Within days, the country lost its AAA rating from S&P Global Ratings, with a two-notch cut.

The pound move turned out to be the main “shock absorber” of the surprise outcome, as the BOE has described the currency’s role. Acting in a political vacuum, the central bank smoothed the immediate market fallout by opening liquidity taps to banks and cutting interest rates.

Those tools will be available to them again, should Brexit precipitate the next crisis.

To contact the reporters on this story: Craig Stirling in Frankfurt at cstirling1@bloomberg.net;Eddie Spence in London at espence11@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: Simon Kennedy at skennedy4@bloomberg.net, Lucy Meakin, David Goodman

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.