There’s No Money in Posh Coffee for Growers Slammed by Pandemic

High-End Coffee Harvest Imperiled by Virus-Fueled Labor Crunch

(Bloomberg) -- Covid-19 is making coffee growing unprofitable for Adan Rojas. Like thousands of small Colombian farmers, the pandemic forced him to use out-of-work locals to harvest his beans as travel restrictions kept out experienced seasonal pickers.

Rookies are fine for standard coffee. But his 17-acre spread in the foothills of the Andes relies on specialty markets for much of its earnings, and beans used in $4 lattes in New York have a much smaller harvesting window. Without access to professionals who can pick five times faster, the cherries that encase the beans over-ripened and fell off the trees.

“You can still sell that coffee, but once it hits the ground, it’s contaminated,” said Rojas, who expects to break even this season. “There’s no way you can sell it as specialty.”

The skilled labor squeeze is the latest pandemic-era blow for growers like Rojas. With many cafes and restaurants still shut, fewer Starbucks lattes are being sold. Futures of smooth-tasting arabica beans have lost 27% this year, closing the gap with more bitter robusta. People are still drinking at home, but it’s typically more standard brews and instant coffee.

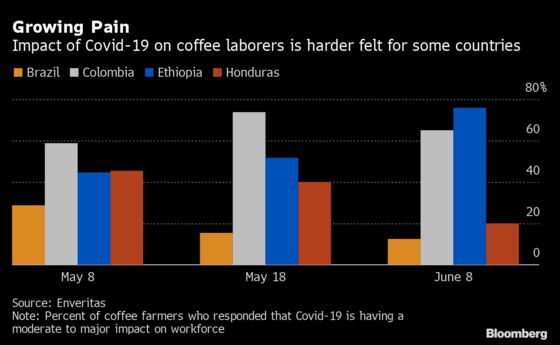

The labor alarm bells are also ringing in Central America, where harvests rely on migrant labor. Weakening currencies help cushion the blow for growers in the region, but the Brazilian real has tumbled even more, making the top coffee nation even more competitive. Brazil’s more mechanized industry is also less exposed to labor disruptions.

While tapping pools of local labor has allowed smaller growers to deal with regional lockdowns and maintain output, hidden behind that success are some worrying signs.

Using friends and neighbors as pickers won’t work when larger producers begin Colombia’s main harvest in September: There simply aren’t enough locals to get the job done.

The industry is counting on an easing of restrictions to allow seasonal workers back in. But letting in more outsiders increases the risk of spreading the disease in areas that so far have contained it much better than big cities.

“I’m very worried about the impact on the harvest in the second half,” said Oscar Gutierrez Reyes, who heads Colombian Agricultural Dignity, which advocates for better prices for growers. “Although we are loosening restrictions, we still don’t know when the peak of this virus will be in Colombia. It’s an incredibly complex situation for farmers.”

Like Colombia, Costa Rica is looking to use pools of locals who have lost their jobs to harvest its mainly premium beans. Normally, growers there rely on pickers from neighboring Nicaragua, but the two countries have traded barbs over measures to fight contagion, with Costa Rica criticizing Nicaragua’s lax response.

Nicaraguan labor probably won’t be available this season amid fears of a second wave, said Xinia Chaves, who heads the Costa Rican Coffee Institute, which is helping develop social distancing and tracing protocols.

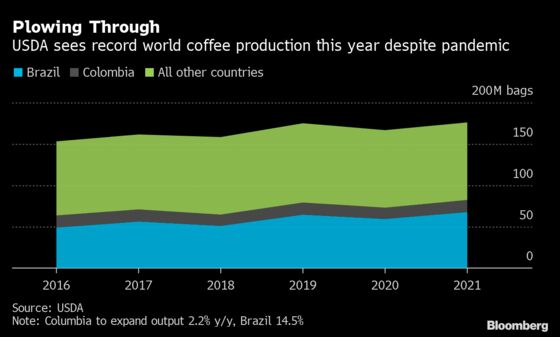

While bumper crops in coffee heavyweight Brazil mean there is plenty of supply, exports from Colombia, Guatemala, El Salvador, Costa Rica and Honduras are all down amid lower demand and logistical delays.

Honduras, Central America’s top exporter, relies on workers from Guatemala and Nicaragua for the harvest that begins in September in some areas. With borders shut, Enrique Salazar, general manager of specialty exporter Bicafe, is worried the industry won’t be able to find enough people. He’s also anxious that roasters and importers will be unable to make their usual trips to inspect beans in situ.

In Ethiopia, Africa’s top producer, specialty exports are up this year. Rather than labor, Covid-19 disruptions there are more focused on inputs to farmers, the impact of which probably will be felt in future production, according to the Ethiopian Coffee & Tea Authority.

As surging rates of Covid-19 in poorer countries threaten harvests, the prospect of supply disruptions is raising concerns downstream. Olam International Ltd., one of the world’s largest coffee traders, has started a fund to help some of its suppliers weather the crisis.

“We want to ensure maintenance of the supply chains to ensure harvest of beans happens as soon as possible without spreading the virus,” Vivek Verma, head of Olam’s coffee business, said by telephone from Singapore. “Coffee prices have already been so low that many farming communities are already on their knees. And then on top of that, with Covid they are scared for their health.”

For growers like Ruber Bustos, it’s the pandemic-driven weakness in demand for exotic coffees that has kept them focused on the standard market where margins are tighter.

Last year, specialty coffee made up about 30% of Bustos’ harvest. In the first half of this year, he won’t produce any. He’s hoping coffee houses will start to reopen and restrictions on seasonal workers will ease in the second half, but says there’s also a risk the virus outbreak will get worse and authorities will have to close regions again.

“Producing exotic coffees needs a lot of skilled labor,” he said. “That labor is very scarce.”

A reduction in demand for specialty coffees can have a lasting impact on farms, according to Kim Elena Ionescu, chief sustainability officer at the Specialty Coffee Association.

“It results in an inability to reinvest, which makes coffee trees weaker and more prone to diseases and ultimately less productive,” she said. “One thing leads to another and then it becomes a problem too large to solve at the farm level.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.