The Climate Science You Missed: Pandemic Winter Edition

The Climate Science You Missed: Pandemic Winter Edition

(Bloomberg) --

No matter how often we hit one, a global temperature record never gets less shocking.

Nineteen of the 20 hottest years on record have occurred in this century—which is only 20 years old. The last six years have been the hottest in the 140-year record. This year will extend that run to seven and may even top the list, according to a recent analysis by CarbonBrief.org.

Extra trapped heat is working its way through oceanic and land ecosystems, setting records almost everywhere. Arctic sea ice fell to its second-smallest area ever at the end of the Northern summer. The smallest 14 sea-ice extents have come in the last 14 years. August, September, and October saw the biggest California wildfires in modern times; they were the hottest months in the state’s recorded history. The number of autumn days with extreme fire weather has doubled since the early 1980s.

On the wet side, this year’s hurricane season saw an unprecedented 30 named Atlantic storms, with as many as 12 making landfall in the U.S.—the highest number ever. An historical analysis found that hurricanes don’t slow down as much as they used to upon hitting land. Super Typhoon Goni hit the Philippines in late October with a one-minute sustained wind speed of 315kph (195 mph), making it the strongest known cyclone to strike land. Climate change doesn’t cause hurricanes, but warmer water and moister air are giving them added fuel.

Scientists have long recognized ocean acidification—a change in the sea’s chemistry that may threaten important marine ecosystems—as global warming’s evil twin. Turns out, there’s a triplet! Biodiversity loss is both a symptom and a cause of not only climate change, but also pandemics. Animal populations have fallen 68% since 1970, and a comprehensive assessment this fall added further evidence to the conclusion that “the underlying causes of pandemics are the same global environmental changes that drive biodiversity loss and climate change.”

Finance has an enormous, untapped role to play in fixing these problems. Former U.S. Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson’s think tank and two research partners produced a 250-page report outlining the global funding shortfall for protecting biodiversity, plus nine financial tools and policies to close it. Not every restored ecosystem packs the same healing power. A high-resolution study of the entire planet shows that focusing on the ecosystems most productive for biodiversity could make restoration efforts 13 times more cost-effective.

Some of the most exciting science continues to occur in the world’s most extreme places. Ten research teams—34 scientists in all—spent two months of 2019 on Mount Everest. Many of their findings add nuance to our understanding of ice retreat, plastic pollution, and other familiar climate trends. There’s also what passes for a silver lining: Global warming is bringing warmer air, higher air pressures, and subsequently more oxygen to Everest’s summit.

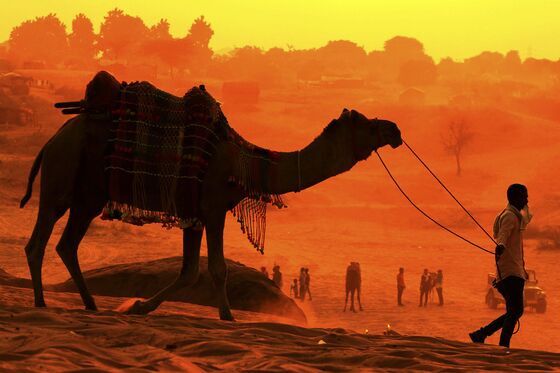

Here’s another fun one, based on studying camels, whose thick fur helps them retain water and, counterintuitively, stay cool. Desert peoples long ago adapted such an idea in their clothing, but MIT researchers have further honed the idea into sophisticated gels that can keep products—think food and vaccines—more than 7C cooler than without them for more than a week at a time. There’s also been progress in meeting the intense and growing demand for more efficient batteries. Nanoengineers at the University of California San Diego have had some success in recycling a critical component of lithium-ion batteries. The process requires up to 90% less energy and emits 75% less greenhouse gas than existing methods.

The best scientists test closely held assumptions to see whether they’re worth holding so closely—or even holding at all. Two social scientists recently failed to find evidence for a bedrock explanation of climate diplomacy: That warming is primarily a “collective action” problem, with nations afraid to act because they don’t trust other countries will, too. The researchers instead argue that countries are more responsive to their own constituencies than they are to potential international cheaters, a conclusion they say should put the search for climate solutions on a more realistic footing.

Eric Roston writes the Climate Report newsletter about the impact of global warming.

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.