(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Early last month, Guyanese President David Granger was knees-down in a community garden brandishing a spade. Granger was there to plant a tree — it was National Tree Day — but also an idea. “Don’t let us get drunk. Let us remain sober,” he told the attentive audience.

Guyana might find that a challenge. Next year, Exxon Mobil Corp. and its prospecting partners will start pumping oil from one of the world’s biggest recent finds: some 5 billion barrels of crude cached in the sandstone deep below the Caribbean floor. The windfall promises to change the energy landscape in the Western hemisphere. Guyana may never be the same.

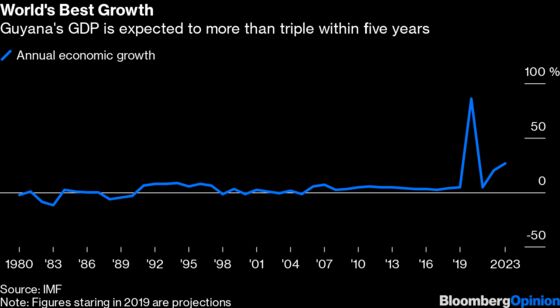

In five years, national output is expected to reach 750,000 barrels a day, making Guyana Latin America’s fourth-largest oil producer and perhaps the world’s largest per capita oil power, generating a barrel per person per day. Oil revenues are expected to climb from zero to almost $631 million by 2024, according to the International Monetary Fund. Income per capita will more than double by next year, topping $10,000. Overall, its economy is projected to grow by 86% next year — 14 times China’s projected growth rate.

Metabolizing so much wealth so quickly — like drinking from a fire hose, as one engineer put it — would be intoxicating for even the sturdiest constitution. For this small, poor country troubled by ethnic strife, with shaky institutions and only the sketchiest plans to put such bounty to use, the system shock could be devastating.

That’s where trees and sobriety come in. To unleash the potential of the coming oil boom, Guyana must accept that wealth and development are cultivated, not simply extracted. Such was the logic behind the Green State Development plan, a wonk’s bet that Guyana can pull off what no other developing nation with an oil bonanza has managed: marshal a massive energy windfall without drowning in riches.

Resource curse, Dutch disease, the paradox of plenty: The name and address of the malediction vary. The outcome does not. Guyana has only to look to Venezuela, the failing petrostate next door that is home to the world’s largest reserves. After years of squandering oil rents on vanity politics and misguided social programs, Venezuela has seen oil output fall by more than half since mid-2018. To escape Venezuela’s fate and that of so many other ailing oil baronies, Guyana has to act now and decisively. The checklist is extensive.

Don’t bring the oil onshore. Sure, such abstinence offends the instincts of the aspiring petrocrat. “It must be in the textbooks they read as children. Every minister of development wants to add value to oil,” said Rice University energy expert Francisco Monaldi. “That’s a big mistake.” Building a tangle of pipelines and refineries is exorbitant, brings marginal returns and makes the host country a magnet for corruption, Monaldi said. One of the headline scandals in Brazil’s Carwash corruption probe was a head-turning case of contract fraud on a grossly overpriced domestic refinery and petrochemical complex launched amid the euphoria over earlier big oil discoveries. Will Guyana heed the experts and forgo investing in iffy refineries? Or will they cave to the temptation once the crude starts flowing?

Resist the local content temptation. Petro-populists typically try to make foreign operators buy a hefty portion of supplies from native providers. That sounds fair enough. But inexperienced domestic companies rarely have the enterprise or production capacity to deliver. Instead, local content becomes an open invitation to padded contracts, subterfuge and waste. Until now, Guyana has avoided the trap of skewing the market by promoting “local champions,” said Marcelo de Assis, head of Latin American upstream research for energy consultants Wood Mackenzie. If Guyana’s nationalist opposition has its way, however, the rules could change.

Get the rules straight. How does a country with one-third of its population living in poverty and a ranking of 164th out of 228 nations in human development manage the haul from what’s likely to be the world’s most profitable new deepwater wells? The short answer: through policy transparency, reliable rules and regulatory acumen, all of which are in short supply. “What we see is a bottleneck, a lack of readiness for oil,” said Assis. “They are scrambling, which indicates that the public sector is not geared to act as a regulator.”

Forge a political pact. Guyana’s conflicted politics are no help. Rival coalitions have been quarreling since last December, when the Granger government lost a confidence vote. New elections are scheduled for early 2020, just as Guyana’s oil is set to flow. Clashing ideas are part of democracy. But with political tensions spilling into the courts and threatening to flare into a constitutional crisis, the risk of judicial delays leading to “legal loopholes and omissions in the oil framework” run high, according to the consultancy Verisk Maplecroft. The political turbulence is troubling news for the Guyanese and their multibillion-dollar stakeholders.

Hire globally. With a population of 780,000, chronic brain drain and no track record in oil extraction, Guyana could use some ringers. Fortunately, the world is flush with savvy oil engineers, geologists and logisticians. But Guyana’s government has been slow to capitalize on global talent, including the nearly half-million-strong Guyanese diaspora. “I don’t understand what’s keeping them from hiring abroad,” said one foreign observer, who has advised the Guyanese government for years. “It’s baffling.”

So is the recent ruling barring binational Guyanese from serving government: Four of Granger’s cabinet ministers with dual nationalities were forced to resign this year. Since some of the most highly trained Guyanese were educated abroad, such scruples amount to a nationalist own goal. The powerful private sector, led by Exxon and its partners, has no such qualms about recruiting expats. Guyana’s government should follow their lead.

Don’t forget renewable energy. Guyana’s electricity currently depends on fossil fuels. With greenhouse gas emissions already reaching 2.6 tons per capita a year, rivaling those of its outsize neighbor Brazil, Guyana could make matters far worse under the coming oil boom. And since much of Guyana’s coastline sits at or below sea level, the deepening climate emergency poses an existential threat. Encouragingly, Guyanese seem to be starting their oil boom with few illusions about the fleeting bounty below their feet. The government wisely, if belatedly, set up a sovereign wealth fund to steward the money. Hence, the official encomiums to agriculture and forestry, and renewable energy, touted to fuel 100% of the power grid by 2040. That’s an admirable goal. Let’s hope Guyana has the temperance and the trees to stay the course.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: James Gibney at jgibney5@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Mac Margolis is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Latin and South America. He was a reporter for Newsweek and is the author of “The Last New World: The Conquest of the Amazon Frontier.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.