This Upstart Brokerage Inspired by Charles Schwab Is Changing the Way Brazil Invests

This Upstart Brokerage Inspired by Charles Schwab Is Changing the Way Brazil Invests

(Bloomberg Markets) -- For almost three decades, Wilson Feldberg kept his money in low-risk investments at Brazil’s biggest bank. Then, three years ago, he started moving almost all of it—the equivalent of about $1.5 million now—to an upstart brokerage, XP Investimentos SA.

Why? Feldberg, who owns a construction company in São Paulo with his brothers, wanted a chance at fatter returns and more personalized advice. “They explained things to me better, and I felt safer following their suggestions,” says Feldberg, a 47-year-old native of Recife. “Since I don’t have much time, I embrace their suggestions.”

Lots of Brazilians are taking the same leap of faith.

XP, Brazil’s biggest retail broker, has been adding 50,000 accounts a month, luring clients like Feldberg away from Brazil’s five big banks and changing the way the country’s middle class saves and invests. With an open-architecture strategy modeled on U.S. financial supermarket Charles Schwab Corp., XP offers stocks, bonds, and funds as well as products previously available only to the very rich, including hedge funds and derivatives. Brazil’s banks, which offered only their own products, have been forced to adapt.

Itaú Unibanco Holding SA, the country’s biggest bank by market value, certainly took notice—especially after clients like Feldberg started moving their money out of it. In 2017 it agreed to shell out 5.7 billion reais ($1.8 billion) for a 49.9 percent stake in XP.

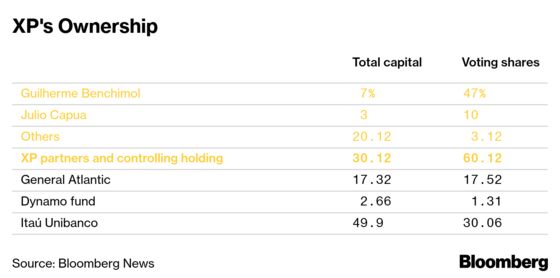

The transaction made Guilherme Benchimol, XP’s chief executive officer and largest holder of voting shares, a billionaire—at least in Brazilian currency, with a net worth of 2.7 billion reais.

XP wasn’t an overnight success.

Benchimol, 41, grew up in a middle-class family in Rio de Janeiro. His father was a doctor, his mother an artist. He played tennis competitively, winning a Rio tournament intended for 11- to 14-year-olds when he was 10. Expected to become a doctor himself, Benchimol tagged along with his father on rounds. But seeing a patient die during a heart procedure turned him away from medicine at age 15. He shifted to finance, starting in the back office of a brokerage when he was 18 and attending college at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

He was 24 when he founded XP with Marcelo Maisonnave in 2001. Originally, they called the company XPTO, a generic placeholder in Portuguese, somewhat like XYZ in English. “We had a very heroic start—fighting banks, the system, getting creamed by everybody,” Benchimol says in an interview at XP’s new offices in Itaim Bibi, São Paulo’s financial center. “In the first year, I thought we would go broke every day.”

As independent financial advisers, Benchimol and Maisonnave realized that retail investors had access to very little information about stocks. So XP started holding seminars. “We rented a place, bought some used computers, juice, sandwiches—and that was our event,” Benchimol says.

After a year he had to sell his car and borrow 5,000 reais from his half-brother, Julio Capua, to keep things going. The number of clients started to rise, however, and XP expanded to 30 offices throughout Brazil. The firm rode a wave of economic growth and a market boom, with Brazil’s benchmark Ibovespa almost doubling in 2003 alone and racking up a total gain of 467 percent in the five years through 2007. XP bought a brokerage firm, grew to 12,000 customers, and was generating 2 million reais a month in revenue.

Then came the 2008 financial crisis. The Ibovespa lost more than 41 percent of its value in one year. All of a sudden, stock brokerage was the worst business in the world, Benchimol says. “No new accounts were opened, everybody started to sell, and we lost clients, one after the other,” he says.

With little to be done, Benchimol decided to take a breather. His plan was to travel and look into what brokerages in Europe and the U.S. were doing to weather the downturn. That was when Benchimol attended a Charles Schwab event in San Francisco. “I was very inspired,” he says. “We decided to follow their model, going beyond just stocks and becoming the first real one-stop investment shop in Brazil, offering everything from funds to bonds from multiple asset management firms, banks, and companies.”

Recovering from the financial crisis was painful. But the firm gained traction with its new approach. Benchimol isn’t coy about XP’s impact. “We democratized the asset management industry in Brazil,” he says. “For the first time, we let small investors talk directly to asset management firms, to insurance companies, to corporations, to banks of any size, anywhere in Brazil.”

XP now has about 2,000 employees, 850,000 customers, and 3 billion reais in annual revenue. It plans to go public, probably on the U.S. Nasdaq exchange, in the second quarter.

While XP has been making inroads, most middle-class investors in Brazil still keep their money in traditional savings accounts. Such accounts, guaranteed by the nation’s deposit insurance fund, are tax-free and generate monthly returns. The government encourages them as a way to support the real estate and agricultural industries—banks are required to direct a percentage of the funds to mortgage or farm lending.

Yet for savers, the accounts are becoming less compelling. In March last year, Brazil’s central bank cut its target Selic rate to 6.5 percent, the lowest level in the benchmark’s history. Savings accounts now pay only about 70 percent of the benchmark rate. That means returns are barely keeping ahead of inflation, which was 3.75 percent in 2018. Even conservative investors are starting to search for higher yields.

Rodolfo Riechert, CEO of boutique investment bank Brasil Plural, says the huge pile of money in Brazilian savings accounts is just waiting to be mined by XP and its copycats. About 779.8 billion reais were parked in such accounts as of November, according to the central bank. Banks still have the lion’s share of client assets in Brazil, with about 95 percent of the total 5.5 trillion reais in assets under management, including companies and individuals. And XP, with roughly 225 billion reais in assets under custody, has 82 percent of the total outside of banks.

A “gold rush” for middle-class savings is coming, Riechert says.

One of XP’s successes was a huge marketing and education effort to promote debt issued by Brazil’s midsize banks. The campaign highlighted the bonds’ guarantee from the country’s privately owned deposit insurance fund. While the promotion raised XP’s profile and revenue, it also introduced new sources of funding for the banks and reduced liquidity pressures in Brazil’s financial system.

By distributing funds from independent firms, XP has helped to develop Brazil’s asset management industry. Overall, investment funds had a net inflow of 449 billion reais from the beginning of 2016 through November 2018, according to Anbima, the capital-markets association.

One beneficiary was Adam Capital, a Rio-based hedge fund that was founded in 2016 and is now among the largest in Brazil. “We believed we would be able to cross the $5 billion in assets threshold but never that we would do it in three years,” says founding partner André Salgado. “Even in our most optimistic scenario, we thought it would take 10 years to reach that.” One key reason for the rapid growth, Salgado says, was that XP and other new distribution platforms helped Adam Capital reach middle-class investors. The Adam Macro Master FI Multimercado fund had a total return of 54 percent from inception on April 29, 2016, through Jan. 2, topping the benchmark interbank rate DI by 26 percentage points, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

Private equity firms picked up on XP’s potential long before banks such as Itaú. In 2010, London-based Actis LLC acquired 20 percent of XP for 100 million reais.

The Brazilian billionaire Carlos Alberto Sicupira followed suit. A co-founder of 3G Capital Inc. and one of the owners of Anheuser-Busch InBev SA, Sicupira took a stake in 2012 through Rio-based Dynamo VC Administradora de Recursos Ltda. Along with Greenwich, Conn.-based private equity firm General Atlantic LLC, Dynamo paid 420 million reais for 31 percent of the company, buying 10 percent from Actis. In April 2016, Dynamo and General Atlantic acquired an additional 16 percent, increasing their holding to 49.5 percent through a capital injection and the acquisition of the remaining 10 percent stake held by Actis. After the Itaú deal, Dynamo has a 2.66 percent stake and General Atlantic about 17 percent.

Using the cash from the investments, XP became a consolidator, buying eight smaller brokerage firms. “Beto Sicupira helps us with good advice on long-term strategy, macro discussions such as raising capital, the IPO, the Itaú acquisition,” Benchimol says.

In addition, XP is using a capital injection of 600 million reais that was part of the Itaú deal to build new businesses, including an insurance company and a bank that will offer loans and no-fee credit cards with below-average interest rates. XP is also opening a cryptocurrency exchange, but without Itaú as a partner.

Feldberg, the construction company owner who moved his savings to XP, says he’s pleased his new brokerage has become more “solid” by joining forces with his old bank. He estimates that his returns are about 40 percent better since moving his money to XP. He’s added a few riskier investments, including hedge funds and project bonds related to a hydroelectric power plant. “Sometimes I don’t have a deep understanding of what I’m getting into,” Feldberg says.

And that could be a problem.

Other clients whose experience wasn’t as positive as Feldberg’s have said they didn’t fully grasp what they were investing in. Some rivals place blame on XP’s compensation policies, which link pay to sales.

“We left the dinosaur age in Brazil only to advance to the cave-man age,” says Tito Gusmão. Gusmão, a former XP partner, is creating a competitor called Warren, in collaboration with Maisonnave, XP’s co-founder. When your pay comes from the product you sell to clients, you’ll push whatever is most remunerative, Gusmão says.

Lelio Rodrigues Faria Sarreta, a former XP client, contends that something like that happened to him, according to documents from a complaint he filed with CVM, Brazil’s capital-markets securities regulator. A market novice, Sarreta had never put his money in anything other than traditional savings accounts, according to the complaint. On XP’s advice, he put 110,000 reais into a structured transaction called a “condor strangle,” a complicated options strategy that bets on low price volatility during a period of time. He wound up losing more than he invested—about 123,000 reais. XP says Sarreta was well-informed about the risks, pointing to email exchanges and his signed authorization.

The case first made its way to B3 SA-Brasil Bolsa Balcao, which registers derivatives in Brazil. The organization decided against a refund, saying the investor was aware of the risks. But Sarreta appealed to CVM, which concluded the transaction was sold to him in a biased manner that didn’t properly outline the risks. CVM determined that XP had to refund his losses. XP says it’s studying legal measures to try to overturn the decision.

Gusmão says the system that Warren is adopting would help avoid those problems: The broker-dealer will charge a fixed fee of 0.5 percent of assets under management, regardless of the products purchased. “That’s the model that’s most typical in the U.S.,” he says.

XP says it sees no conflict and that its model allows clients to avoid fees. Clients are offered an option of paying a fixed management fee and leaving asset purchase decisions to the firm.

XP’s growth has created some hurdles. Brazil’s central bank imposed restrictions on the Itaú deal to make sure the growing firm doesn’t stifle competition. Regulators extended the time that must pass before Itaú could make additional investments in XP, demanding new approvals for that, and said neither company can buy other digital investment platforms. Itaú also is prohibited from accessing information about XP’s clients and suppliers for 15 years.

Big banks, which can feel the ground shifting, are scrambling to respond. Banco Santander SA’s Brazilian unit is launching a digital investment platform, CEO Sergio Rial told reporters in 2018. Named Pi, it will offer a range of third-party products. Banco do Brasil SA, the nation’s largest by assets, has also started selling funds from independent asset managers to higher-income clients. Both banks announced in September they won’t charge custody fees to hold Treasury bonds for clients.

Banco Bradesco SA, according to Morgan Stanley analysts, “seems to be a step behind peers in tuning their business model to compete with fintech players.” CEO Octavio de Lazari said in an interview in November that the bank, the second-biggest in Brazil by market value, is addressing that issue. Integration of the bank’s brokerage firms with its private-banking and high-net-worth Prime businesses, which started last year, will help create a unique investment platform, Lazari says.

Banco BTG Pactual SA started a digital platform in 2016 and is in court and antitrust battles with XP after recruiting some investment advisers from the firm. “Brazilian families’ wealth will be gradually distributed between the traditional banks and the new digital investment platforms, as it already is in the U.S.,” CEO Roberto Sallouti said at a press conference.

Before buying into XP, Itaú created its own open digital platform, which still operates and competes with XP.

XP, meanwhile, continues full steam ahead. The company’s new São Paulo headquarters, which opened in 2018, is already running short on space, Benchimol says. And XP’s goals are ambitious: growing assets under custody to 1 trillion reais by 2020, a fourfold increase, and raising its number of investment advisers to 10,000 from 3,700.

“Brazil is starting to get hot again,” Benchimol says. “More people will come to invest here, and we’ll need more brokers and analysts,” he says. “Our structure could grow fast.”

Marques, Lucchesi, and Andrade are reporters at Bloomberg News in São Paulo.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Jon Asmundsson at jasmundsson@bloomberg.net, Steve Dickson

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.