Guaido Is Seeking to Make Payment on Citgo-Backed PDVSA Bond

Guaido Is Seeking to Make Payment on Citgo-Backed PDVSA Bond

(Bloomberg) -- The finance team working with Venezuela’s National Assembly leader Juan Guaido is leaning toward asking the U.S. for permission to use an escrow account to pay a bond from the state oil company that’s backed by Citgo, according to people involved in the discussions.

The $71 million interest payment on PDVSA notes maturing in 2020 is due on April 27 and failure to transfer the money to creditors could trigger a rush to seize the U.S. refiner, which was recently taken over by a Guaido-appointed board. Venezuela’s embattled President Nicolas Maduro, who has been deemed illegitimate by more than 50 countries, no longer has an incentive to pay the bond since he’s already lost control of Citgo.

“All obligations will be honored since they’re key to the protection of state assets,” Jose Ignacio Hernandez, Guaido’s newly appointed U.S.-based Attorney General, said in a telephone interview from Boston.

The Citgo escrow account may hold as much as $560 million, according to one of the people, who asked not to be identified discussing internal deliberations. But to use the money for the bond payment, Guaido’s team would need an OK from the U.S. Treasury Department’s Office of Foreign Assets Control. Discussions are continuing among Guaido’s team on legal and debt strategies, the people said.

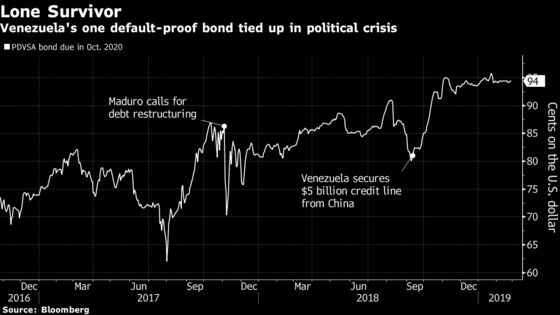

The PDVSA 2020 bond is the only Venezuelan debt security that has yet to fall into default, as Maduro prioritized payments to ensure he wouldn’t lose the collateral, a 50.1 percent stake in Citgo Holding Inc.

Because the bonds are asset-backed and Venezuela has kept paying them, they’re quoted at 94 cents on the dollar, compared with an average price for Venezuelan and PDVSA debt around 30 cents.

After Maduro was sworn in for a new term Jan. 10, Guaido emerged to stake his claim to the presidency citing articles in the constitution. Since then, Venezuela has had two presidents of sorts and Guaido named his own boards to state oil company PDVSA and to Citgo. Despite not having physical control over PDVSA assets in Venezuela, given that the U.S. government has recognized him as the rightful leader of the South American country, he could receive favorable rulings to actions brought before U.S. courts.

If Guaido’s camp decides not to pay the PDVSA bond, or if it can’t get permission to access the escrow funds for that purpose, it may be a while before investors see a resolution.

“Make some popcorn because this is going to be a long movie,” said Ray Zucaro, the chief investment officer at RVX Asset Management in Miami, who holds PDVSA debt but not the 2020 notes.

If the Maduro-controlled PDVSA board opts to default on the debt, bondholders may find themselves competing with other creditors to collect on the Citgo collateral. The long list of potential claimants includes ConocoPhillips, Crystallex and other firms that have sued the state oil company or government for defaulting on various obligations. Making matters even more complicated, the other 49.9 percent of Citgo not backing the bonds has been pledged to Rosneft, Russia’s state-run oil company, as collateral for a $1.5 billion loan.

“The incentives of the current administration in Venezuela to continue paying the PDVSA 2020s have probably declined significantly as a result of the sanctions and the resulting changes in Citgo,” said Shamaila Khan, director of emerging-market debt at AllianceBernstein in New York.

One other potential scenario is that PDVSA defaults on the bond and the Trump administration issues an asset protection order to prevent bondholders from laying claim to Citgo. This strategy was deployed in Iraq after the 2003 invasion, which kept creditors from seizing local assets.

If the U.S. were to make such a ruling, “it could take 5 to 10 years or even more for a new government to say the oil sector is comfortably running again,” a prerequisite to getting the order lifted, said Cecely Hugh, investment counsel in emerging-market debt at Aberdeen Standard Investments in London. “It wouldn’t be until then when bondholders could think about attaching or claiming assets.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Lucia Kassai in Houston at lkassai@bloomberg.net;Fabiola Zerpa in Caracas Office at fzerpa@bloomberg.net;Ben Bartenstein in New York at bbartenstei3@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: David Marino at dmarino4@bloomberg.net, ;David Papadopoulos at papadopoulos@bloomberg.net, Daniel Cancel, Brendan Walsh

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.