Green Property Debt Come With Opaque Climate Standards

Green Property Debt Frenzy Comes With Opaque Climate Standards

(Bloomberg) -- The 50-floor building designed to look like a bundle of chopsticks will stand out in China’s industrial hub of Shenzhen. It will also use natural ventilation, have a green roof and collect rainwater for irrigation -- but that’s not unusual these days.

The Kaisa Group Holdings project is just one of hundreds around the world being driven by green bonds. Property firms have been among the cheerleaders of a rush to ethical finance, posing a challenge for investors to scrutinize how green this building frenzy actually is, at a time when debt from the sector is under pressure on contagion from distressed developer China Evergrande Group.

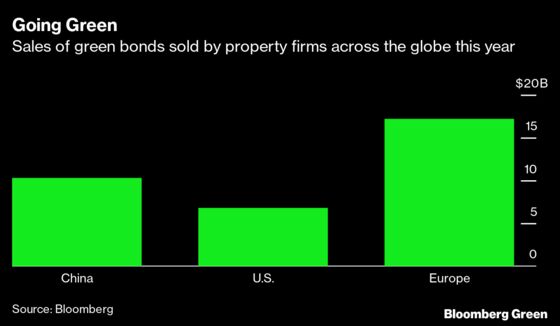

In China, sales of green debt from developers surged to $10.3 billion so far in 2021, more than three times the whole of 2020. It’s a similar picture in Europe, where they have more than doubled to $17.2 billion and make up about a sixth of the corporate green market. In the U.S., they have surpassed last year at $6.85 billion, nearly a quarter of the total.

Investors are clamoring for the chance to put their money to environmental use, yet may just be fueling more development from a building and construction sector that accounts for about 40% of energy-related carbon dioxide emissions. Finding the companies actually cutting pollution means sifting through a heap of building certifications and sustainable bond rules, which obscure potential greenwashing.

“The use of proceeds from green bonds in the real estate sector focuses on energy efficiency -- heating and cooling of buildings -- and not so much on environmentally harmful factors from building materials such as cement,” said Jyri Suonpaa, a green bond fund manager at Alandsbanken Abp in Finland. “New issuance from the sector is a lot higher than from other parts of the market, which increases the risk of greenwashing.”

Property developers selling sustainable bonds usually refer to either international green building certifications such as LEED and BREEAM, or local standards such as the Chinese Green Building Rating. These score elements of the design or performance, from construction materials and energy performance to air quality and water efficiency.

“The commitment to third-party assurance is absolutely critical to make sure companies avoid the charge of greenwash,” said Breana Wheeler, U.S.-based operations director at BRE, which administers BREEAM. “It’s so important that for green bonds there is a verified outcome.”

The sector is under pressure to up its game as governments tighten long-term emissions targets. Yet green bond issuance for property has faced little criticism, unlike sales of such debt from other high-emitting industries such as aviation and oil.

Each year, more than 4 billion tons of cement contribute around 8% of global carbon dioxide emissions, and that’s growing with rapid urbanization, according to a Chatham House report. Efforts to cut this footprint lag behind industries such as electricity and transport.

In China, privately run non-profit certification could help some companies to greenwash, said Elsa Pau, chief executive officer of financial analytics firm BlueOnion and a long-time consultant for responsible stewardship in family offices.

“We need a system to measure these buildings using the same specs as would be expected of a public company,” Pau said. “Unfortunately, many use of funds are going toward controversial projects that are potentially creating more environmental problems.”

Kaisa, which is funding the Shenzhen development from the $600 million in sustainability bonds it sold last year, added 11 green building certification projects to its pipeline in 2020. In the U.K., one of the biggest issuers this year has been Canary Wharf Group Plc, which is building a residential and office development called Wood Wharf in London. It says developments aspire to be carbon neutral, yet declined to give details.

In U.S. real estate, the biggest sustainable bond issuers this year have been Boston Properties Inc. and Equinix Inc.

The main player in property debt, Fannie Mae, doesn’t issue green bonds in the corporate debt markets. Instead, it buys environmentally-friendly mortgages from a pool of lenders and converts them into mortgage-backed securities to finance residential buildings. Property owners need to commit to slashing energy and water usage by at least 30%, with a minimum of 15% savings from reduced energy consumption or renewable energy generation to qualify for a green loan from a lender.

CICERO, which provides environmental ratings for bonds, labeled the Fannie Mae framework only “light green” last year. While it said the system encourages green mortgages and energy efficiency, the requirements fall short of fully aligning the U.S. housing stock toward a low-carbon future.

Property Overexposure

Despite these concerns, the property green boom looks set to continue, with the benefits clear for developers. Buildings with sustainable features attract more investors and tenants, according to Franck Delage, senior director for EMEA real estate at S&P Global Ratings. London offices with the highest sustainability ratings command rent premiums of more than 12%, according to broker Knight Frank.

Some ethical funds may end up reconsidering buying new property bonds simply because exposure to real estate within their green debt portfolios is getting too high. In Sweden, such bonds are half the total.

“The bias toward real estate in green bonds makes diversification more difficult,” said Alandsbanken’s Suonpaa.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.