Hottest New Fuel Proves Hard to Handle

Hottest New Fuel Proves Hard to Handle

(Bloomberg) -- The universe’s lightest and most plentiful element turns out to be a fickle fuel to manage.

Hydrogen has a tendency to pass through valves and gaskets on equipment designed to harness the energy of larger methane molecules in natural gas, said Robert Koubek as he moved among a labyrinth of pipes at the power plant he operates outside of Graz, Austria’s second-biggest city. That means utilities like Verbund AG need to begin testing for safety now in order to have machines up and running by the end of this decade.

“It’s a tricky gas and its flame burns differently,” Koubek, 54, said during a June tour of Verbund’s Mellach facility. “But we’re making the transition from fossil fuel to renewables, so we have to determine whether it’s suitable for scaling up.”

The engineers helping him do that job 200 kilometers (124 miles) south of Vienna are a key cog in a vast and growing collection of laboratories and companies pouring resources into making hydrogen economical. The European Union is considering billions of euros of incentives to boost production. Germany approved a national strategy costing 9 billion euros ($10 billion) that focuses on generating hydrogen with solar and wind energy.

“We have to find a solution for decarbonizing the economy and that’s where hydrogen comes in,” Austria’s climate minister Leonore Gewessler said in an interview with Bloomberg. “It’s part of an industrial strategy.”

Austria has committed to getting all of its power from renewables by 2030, putting an end to natural gas generation in the next 10 years. Oil, which is still used to heat hundreds of thousands of homes, will be eliminated by 2035. Altogether, the country of 9 million wants to reach climate neutrality a decade before the EU’s 2050 goal.

To help reach those targets, state-controlled Verbund is recruiting researchers from across Europe to plug into its gas plant in Mellach, offering companies a test bed where they can monitor new hydrogen technologies under real-world conditions.

“For the hydrogen economy to work, we need to use the existing asset base,” said Carlos Lange, the chief executive officer of Innio Group, an Austria-based spin-off of General Electric Corp. that’s testing hydrogen-fuel engines and is in talks to join Verbund’s project. “Our responsibility is to show the world what’s possible and ensure that we’re ready once hydrogen’s achieved economies of scale.”

Innio is already generating electricity with hydrogen in Argentina, Germany and Japan. It’s testing a 2.5-megawatt unit at the Large Engine Competence Center Gmbh, a laboratory near Mellach that’s run in conjunction with the region’s technical university.

“We need big changes and can’t just fiddle around the edges,” said Nicole Wermuth, a senior engineer who worked with General Motors in Michigan before joining the lab.

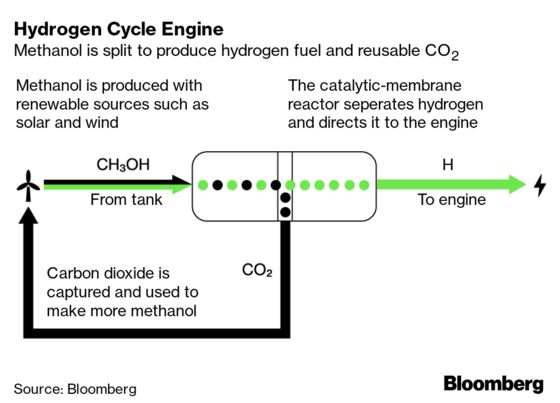

Wermuth and her colleagues are using Innio’s engine to devise a new hydrogen-fuel cycle for heavy transport like freight ships and diesel locomotives. Rather than trying to capture and store hydrogen directly, they’re using commonly-used methanol as an agent to transport the hydrogen.

A secretive catalytic-membrane reactor developed by researchers at Germany’s Fraunhofer institute separates and directs hydrogen molecules into the engine, while sequestering liquid carbon dioxide into tanks, which can later be reformed into new methanol by using renewable energy. That project, whose other partners include London-based technical services provider Lloyd’s Register Group Ltd., is entering the final phase of testing this year and plans to deploy its first hydrogen ship engine on a Swedish ferry after that.

It can cost upwards of 7 million euros to construct a lab capable of testing hydrogen technologies over a span of several months, according to Andreas Wimmer, the CEO of the Large Engine Competency Center. He helps companies like Innio to optimize the thermal dynamic performance of their engines by setting up hundreds of sensors that monitor and record how hydrogen burns.

“Hydrogen is very easy to combust, with an ignition ratio that’s wider than other fuels,” he said, referring to the relatively low amount of energy required to burn the gas. Wimmer pointed to the 1986 Challenger space shuttle explosion as an example of what can happen when hydrogen leaks

That’s a key issue for Koubek back at Verbund’s plant in Mellach. He’s already drip-feeding the element into the plant’s natural gas pipes but Siemens AG will only guarantee the performance of their turbines with a maximum of 3% hydrogen in the mix, he said.

Germany’s Sunfire GmbH has installed a modular high-temperature electrolysis unit in the shadows of Austria’s last coal-fired power station that’s helping Koubek’s team test out the new reality.

“It was very emotional happening when the coal era came to a close on March 31 at 10:19 p.m.,” said Koubek, reciting from memory the precise time that the plant was shut down. “But we can’t be sentimental. It was good for a time but now we have to move on.”

©2020 Bloomberg L.P.