Google May Employ More People Than the Entire U.S. Newspaper Industry

Another milestone has been passed (sort of) in the supplanting of legacy media. There are some problems with that.

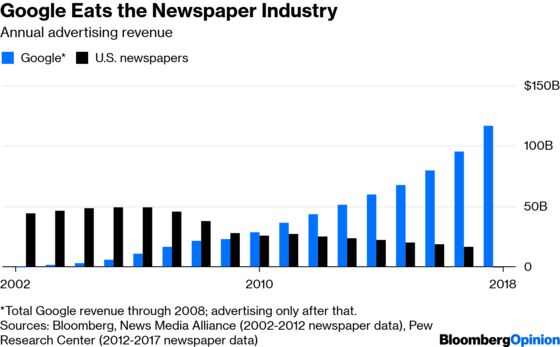

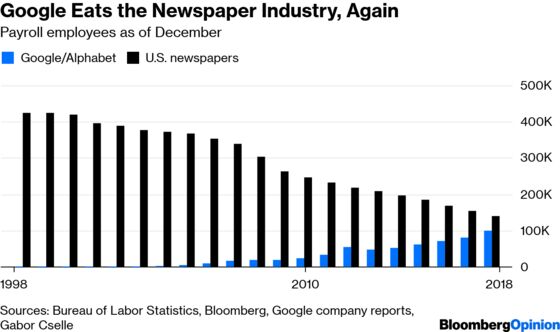

(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Alphabet Inc., which is almost entirely Google, had 98,771 employees as of December. That news, contained in the annual 10-K report the company released last week, got me thinking. Google, you may remember, passed the entire U.S. newspaper industry in advertising revenue in 2010. The numbers are now not even remotely close.

With 139,900 payroll employees as of December, U.S. newspapers are still ahead of Alphabet. The trend is clearly not their friend, though, and there’s a twist to the story. Last July, Bloomberg’s Mark Bergen and Josh Eidelson reported that Alphabet employs about as many “red-badged contract workers” as white-badged full-benefits staff.

Earlier this year, those contractors outnumbered direct employees for the first time in the company’s twenty-year history, according to a person who viewed the numbers on an internal company database.

If Alphabet’s contractors in fact outnumber its employees, then it may really have 200,000-plus people working for it, far more than the U.S. newspaper industry. Yes, newspapers have stringers and other contract workers who don’t show up in their payroll employment counts, either, and the Alphabet numbers are global while the newspaper numbers are not. It’s not that meaningful a comparison. But it’s still … unsettling.

In the second half of the 20th century, newspapers in the U.S. made money mainly by selling ads. They used some of that money to hire journalists, but they also had lots left over for the owners. In 1997, the average operating profit margin of American newspapers was 19.5 percent. Gannett Inc.’s was 26.6 percent. These big margins came under lots of criticism as newspapers began to struggle in the 2000s. I remember talking to Craig Newmark of Craigslist in those days and his message was that newspaper owners needed to stop whining so much about lost classified-ad revenue, stop laying off journalists, and get used to smaller profit margins. They did get used to lower profits — Gannett’s operating margin for the four quarters ending in September was 6.1 percent — but, as is clear from the above chart, they didn’t stop laying off journalists.

Now, of course, it’s Google and Facebook Inc. that make scads of money selling ads and boast big operating margins: Alphabet/Google’s was 22.9 percent in 2018, Facebook’s 44.6 percent. They assemble audiences in a far more cost-effective and targeted way than newspapers ever did. In recent years, they have also gotten to be big employers (Facebook reported a headcount of 35,587 as of Dec. 31). What they don’t do, with occasional exceptions, is hire journalists.

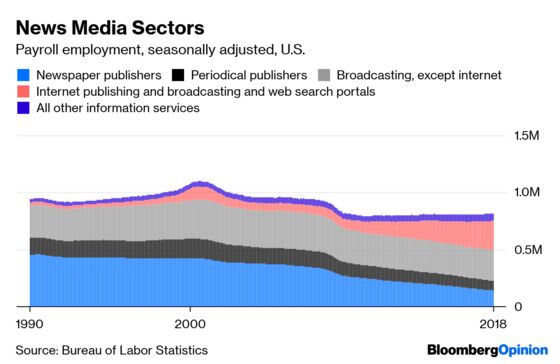

Here’s employment in the main industry sectors that do hire journalists:

At first glance, it looks like the overall job losses stopped in 2010. But that ungainly and fast-growing category of “Internet publishing and broadcasting and web search portals,” while it includes a lot of digital-only journalists, covers most employees at Alphabet and Facebook, too. “All other information services,” which has also been growing, includes, well, me, alongside libraries, archives and some other things. The broadcasting sector, which has shrunk a little but held up much better than newspapers and magazines, has lots of its employees on the entertainment side. (The motion picture and sound-recording industries employ almost twice as many people now as in 1990, but as they’re even more heavily entertainment-focused, they didn’t seem to really belong on the chart.)

A more direct if less reliable and timely measure here is the annual count of “reporters and correspondents” from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ annual Occupational Employment Statistics. There were an estimated 38,790 in the U.S. in May 2017, down from 53,060 in 2006. The same basic story, in other words — with the added twist that by now there are probably fewer reporters and correspondents than Facebook employees.

Lots of other jobs have been wiped out by technological change over the centuries, so it can seem a bit self-involved when a journalist dwells on lost journalism jobs. OK, it is self-involved. But journalists do play a useful societal role, one that has yet to be effectively taken over by artificial intelligence, crowdsourcing or other innovations. And while a mix of new business models, previously neglected older business models (subscriptions, mainly) and nonprofit funding sources will probably be enough to keep national journalism going on a tolerably effective scale, at the local level, things really don’t look encouraging.

Scholars are starting to quantify the effects of this loss of local journalists. A study published in December by two communications professors and a political scientist concluded that local newspaper closures made voters more likely to vote a straight political ticket, thus increasing partisan polarization. “When they lose local newspapers, we have found, readers turn to their political partisanship to inform their political choices,” the authors concluded. Earlier last year, a study by three finance professors found that municipal borrowing costs go up 0.05 to 0.11 of a percentage point after a local newspaper closes, with the authors arguing that “loss of government monitoring” accounted for the rise. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but as Bloomberg’s Danielle Moran explained, “For a $65 million debt issue, that amounts to about $71,500 annually — enough to cover a teacher’s salary — or about $2 million over the life of a 30-year bond.”

Google does lots of useful things, and it now employs lots and lots of people. But they generally don’t show up at city council meetings and ask difficult questions.

I include the name Alphabet when I talk about employment but not when I discuss ad revenue because Alphabet has employees outside of Google, but it doesn't contribute to ad revenue.

Newmark has since changed his tune somewhat, donating $20 million last year to what is now called the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York.

The BLS aims to measure payroll employment by establishment, not company, so a free-standing Facebook or Google data center or Google Fiber operation might show up under another industry category. Also, no, I’m not sure where the BLS found 29,000 internet publishing and broadcasting and web search portal employees in 1990. AOL, Compuserve and Prodigy can’t together have had that many employees then, can they? The current internet publishing and broadcasting and web search portals category descended from bits and pieces of a bunch of earlier industry categories that you can trace here, but doing so still doesn't really answer the question.

Also, in this accounting, broadcasting includes cable TV.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Brooke Sample at bsample1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. He was the editorial director of Harvard Business Review and wrote for Time, Fortune and American Banker. He is the author of “The Myth of the Rational Market.”

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.