Glitter Is Litter Campaign Hits Class of '19

Glitter Is Litter Campaign Hits Class of '19

(Bloomberg) -- It’s commencement season, and college campuses are contending with an ugly glitter problem.

Robe-clad graduates at Texas A&M University are flocking to the campus’s most picturesque spots to pose for photos beneath a shower of sparkly plastic bits. The colorful mess left behind is nearly impossible to clean up, threatening to wash into nearby White Creek, said Joseph Johnson, manager of The Gardens, a new outdoor education center.

“As I’m walking through The Gardens, I’m constantly picking up glitter,” Johnson said. “It’s an issue all over campus.”

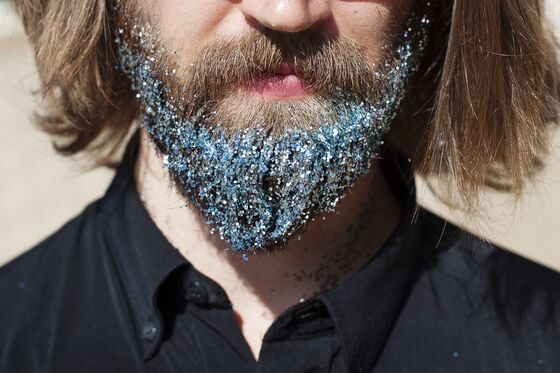

Glitter has become a social media sensation, driven by the ante-upping culture of picture-sharing websites such as Instagram and Pinterest. About 10,000 tons are produced each year, according to U.K.-based glitter maker Ronald Britton Ltd. Used in ever-more creative ways, the shimmering plastic sprinkles bring an extra luster to photos, crafts, cosmetics and even car paint. Many posers go for impact with glitter-coated beards, tongues or other body parts.

But here’s the rub: All that glitter is not good. As soon as it lands on the ground, it’s just litter, contributing to a growing plastics-pollution crisis that threatens the health of the world’s wildlife and oceans.

“It’s a problem that is really hard to clean up,” said Kate Melges, senior oceans campaigner at Greenpeace. “It’s a hazard to our health and marine life.’’ Above all, “Is it really necessary? Not really.”

Glitter pollution is becoming especially acute at university campuses across the country, from California to North Carolina. Student groups and administrators are adopting the #GlitterIsLitter hashtag on social media to drive home the message that the glimmering scraps are hurting our environment.

Glitter is typically made from sheets of polyethylene terephthalate, or PET, backed with a thin layer of aluminum and cut into tiny pieces. The aluminum poses little environmental threat, but the PET plastic could persist for 1000 years, said Tori Miller, a materials science professor at North Carolina State University. Until then, each plastic bit will remain a hazard to wildlife, she said.

“All of the plastic that has ever been manufactured still exists, which is kind of horrifying,” Miller said.

As with all microplastics, defined as smaller than 5 millimeters, there is no efficient way to collect and recycle glitter, and wastewater systems fail to capture the small pieces, Miller said. North Carolina State has “massive glitter problems” at scenic campus locations such as the Memorial Belltower, she said.

Microplastics make up the bulk of ocean debris, the U.S. National Ocean Service says. The ocean currently holds about 150 million tons of plastic waste, an amount that increases by at least 8 million tons every year.

Don’t blame glitter for that, said Joe Colleran, general sales manager at Meadowbrook Inventions, a New Jersey-based glitter maker. Hating on glitter is just a distraction from far bigger sources of marine pollution, such as the plastic bottles and snack packaging produced by Coca Cola Co. and PepsiCo Inc., he says.

“The amount of plastic pollution from glitter is inconsequentially immeasurable,” Colleran said. “You can’t find it in the ocean. It’s a farce that there is a big issue about this.” Still, he said, the company now has a cellulose-based product called Bio-Jewels that “is probably the future.”

“We’ll make whatever people want,” he said.

Jennifer Hickle Carpenter has been photographing Texas A&M graduates since 1987 and hates seeing the trash left behind by other photo sessions. On Monday morning, she spotted custodians trying to sweep up glitter at the campus entrance, a popular spot for graduation photos. Signs warning against glitter litter don’t seem to help.

“People aren’t paying attention,” Carpenter said. “It started in the last five years and has really picked up in the last year.”

Just last month, Seventeen magazine ranked setting off a glitter cannon as the No. 1 way to improve graduation pictures. Sparkles made another appearance at No. 8, “Because everything is better with glitter,” the magazine said.

Schools aren’t the only ones coping with the fallout. In the U.K., 61 music festivals are banning glitter as they eliminate single-use plastics. The Burning Man festival in Nevada has long banned the glistening plastic as organizers strive to leave behind no trace of the annual desert gathering.

Trisia Farrelly, an environmental anthropologist at Massey University in New Zealand, wants a worldwide glitter ban. She paints a sinister picture of the dangers of microplastics to “humans, animals, soil, air, and fresh and marine ecosystems.”

Meanwhile, glitter is finding new outlets, including in a sunscreen called Unicorn Snot.

Sustainable Alternatives

Ronald Britton is responding to the backlash with a product called Bioglitter made from plant-derived cellulose that biodegrades in water. The company has increased production capacity five times since Bioglitter was introduced in 2015, with sales more than tripling last year, said commercial director and co-owner Stephen Cotton.

Bioglitter sales to the cosmetics industry now outpace the company’s cheaper, traditional product, and other markets are following, he said.

“The interest has just ballooned out of all proportion,” Cotton said.

The controversy reminds Texas A&M’s Johnson of the organized helium-balloon releases of generations past.

“Eventually everyone realized what goes up comes down, and it’s litter,” Johnson said. “Now we have glitter. It’s a new thing we have to teach.”

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Susan Warren at susanwarren@bloomberg.net

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.