Getting to Net Zero Means a Race to Scale Up Renewables

Getting to Net Zero Means a Race to Scale Up Renewables

(Bloomberg) --

As global leaders prepare for climate talks in Glasgow, there's a growing urgency to cut down reliance on polluting fossil fuels to limit the worst effects of global warming. For that effort to be successful, clean energy will have to grow rapidly to make up the difference.

After years of declining costs, wind and solar are the cheapest ways to generate new electricity in most of the world. That’s helped deployment of new renewables surge in recent years. But the scale of investment will need to continue to ramp up in the coming years.

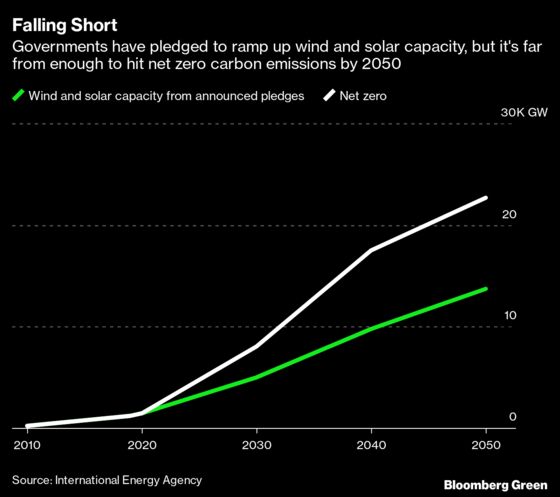

To give policymakers a clear view of the size of the task at hand, the International Energy Agency forecast the difference between the amount of renewables that would be delivered under current national climate pledges and what would be required to have a chance to limit global temperature increases to 1.5° Celsius compared to pre-industrial levels. For example, the trajectory for wind and solar capacity will need to increase by about two thirds in 2050 compared to today’s pledges.

“Renewables are the cornerstone of decarbonization strategies,” said Brent Wanner, who manages power sector modeling for the IEA. “In the lead-up to COP26, we’re seeing and welcoming more ambition. But to date those commitments aren’t nearly in line with a net-zero emission by 2050 pathway.”

So what would a net-zero pathway actually look like for renewables growth? In the coming years, annual deployment would have to be roughly quadruple the amount of wind and solar added last year, already a record. That pace would have to be maintained through the 2030s and into the 2040s to have enough clean power to burn fewer fossil fuels even as overall energy demand increases.

By setting a clear direction of travel, companies can start to get the materials in line necessary for the buildout. Wind and sunshine are free, but the panels and turbines that harvest their energy require materials, including steel. By the 2030s wind and solar projects would need about the amount of steel that’s produced annually in the U.S., the fourth-largest supplier globally. The world has plenty of the material, but companies have to plan out the processes needed to manufacture and deliver all the solar panels and wind turbines that will be utilized.

“Those supply chains take time to develop,” Wanner said. “If we want to get there, we have to start now.”

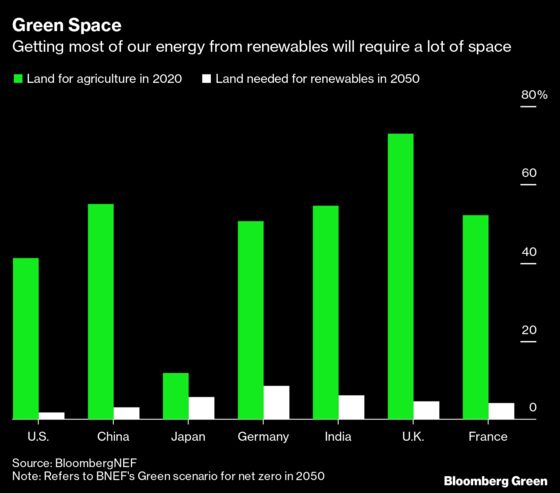

Another main consideration is space. Traditional fossil fuel power plants are relatively small, while solar farms and wind parks can spread out for miles. In the net-zero emissions scenario with the greatest amount of wind and solar modeled by analysts at BloombergNEF, those clean power plants would take up 3% of land in China and 2% of land in the U.S. Governments will need to make those areas available to developers.

“There’s plenty of space, but it’s a political solution,” said Seb Henbest, chief economist at BloombergNEF.

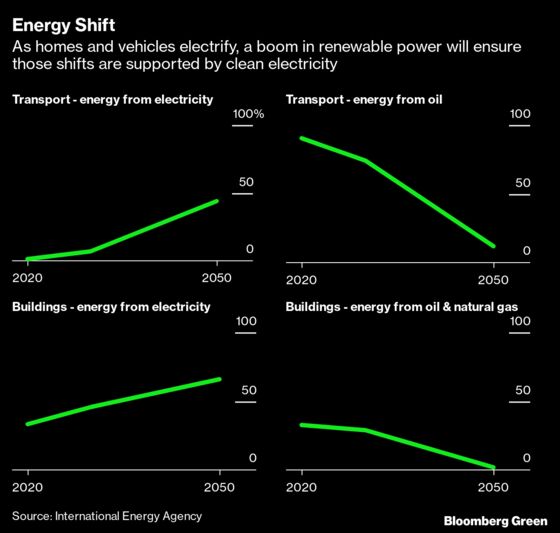

All that doesn’t mean fossil fuels will disappear right away. They’ll still make up a sizable share of energy use in 2030, even as electric heat replaces natural gas in homes and batteries take over for internal combustion engines in vehicles. The question is how fast that transition happens. To stay within 1.5C, renewable energy will have to become the primary source of fuel for daily living at a much faster rate than what’s happening now.

All the projections about how fast and how much renewables will be necessary are meant as sign posts for the policy makers. Even if, say, the world isn’t on track by the end of the decade to hit net-zero emissions in 2050, it doesn’t mean that won’t happen.

“If it’s not possible to achieve in a certain timeframe, does that mean you shouldn't bother trying? The answer is no,” said BNEF’s Henbest. “You’ll just have to go faster later.”

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.