Defiant China Scientist Says He's 'Proud' of Gene-Editing Work

Gene-Editing Chinese Researcher Says He's Willing to Push Ethical Boundaries

(Bloomberg) -- The Chinese scientist who ignited a backlash over creating the world’s first genetically-altered babies is undeterred by the global condemnation that his work has sparked and believes history will be on his side when the dust settles.

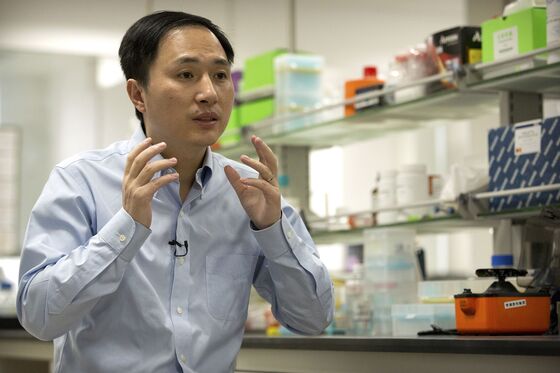

He Jiankui, a researcher in the southern Chinese city of Shenzhen, was a virtual unknown in the world of genetics research and to others outside it. That changed this week after he said he had altered the genes of a pair of twin girls while they were embryos in a bid to make the recently-born babies resistant to infection by the virus that causes AIDS.

The soft-spoken outsider didn’t just get instant fame. He was rebuked by his university, other scientists, and even a government official, who said that any gene editing for fertility purposes was unlawful. A group of 122 Chinese scientists issued a joint statement decrying He’s actions as “madness” and asked the government to regulate the work.

When the mild-mannered researcher got on stage at an international genetics conference in Hong Kong Nov. 28 to share data and details about this project, he spoke softly and haltingly, with a tad of nervousness. He started by apologizing for the furor in the scientific community and said a news leak had forced him to prematurely move ahead with public announcements of his project.

Then, He stuck to his ground. “I feel proud,” he said discussing the case of the twins who were given the pseudonyms Lulu and Nana, whose genes he had edited. He also disclosed that there may be a second “potential pregnancy” with a gene-altered embryo, though it was unclear from his answer whether that pregnancy was still viable.

His work was based on “compassion” for those affected by genetic diseases such as HIV, said He. When asked if he would have done this to his child, He didn’t flinch: “If it was my baby, with the same situation, yes I would try first.” He has declined to be interviewed.

To get him to this controversial breakthrough, He worked almost alone. His research team appears to consist of one other fully-qualified scientist, the embryologist Qin Jinzhou, who conducted the actual gene surgery and in-vitro fertilization, according to a YouTube video posted earlier in the week explaining his project. The scientist, a soccer fan in his mid-thirties used a technology called Crispr, a state-of-the-art tool now widely used for the modification of genes in research.

He denied that he had worked in secrecy, in response to a question at the conference, and insisted all the parents in the trial were well-educated and understood the risks in the study.

That hasn’t stopped his peers from distancing themselves from him, even those He consulted in the research process.

William Hurlbut, an adjunct professor in neurobiology at the Stanford Medical School whom He consulted with over the past two years, said he knew the researcher was headed in that direction but didn’t know he had actually implanted edited embryos. “I challenged him at every level and I don’t approve of what he did,” Hurlbut said.

He seems to have anticipated some of the backlash, if not the severity of it. “I understand my work will be controversial, but I believe families need this technology, and I’m willing to take the criticism for them,” He said in one of the YouTube videos.

“We believe ethics are on our side of history,” He said in another video described by ScienceNet.cn, a publication of China Science Daily which is backed by the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

The researcher is based in China, at the Southern University of Science and Technology, or SUSTC, in Shenzhen, but did his graduate and post-graduate training in the U.S. He got a Ph.D. at Rice University in Houston, then did further research work at Stanford University in California from 2011 to 2012 before returning to China, according to his biographical page on SUSTC’s website.

There’s little clue in his background that He would become controversial for a first-in-the-world human experimentation. He’s earlier work in the U.S. was largely theoretical and focused on biophysics and computational genomics, according to published papers and a U.S. researcher who worked with him in the past.

One of his first academic papers on Crispr was published in 2010 by a physics journal and focused on a theoretical model of how bacteria use gene-editing to defend themselves. During post-doctoral work at Stanford, his research focused on computational genomics, according to the researcher, who described He as bright, ambitious, outgoing and entrepreneurial.

He now faces at least three investigations in China and calls from prominent Chinese researchers for him to be punished. A senior Chinese government official has said his work is unlawful.

The SUSTC said it was “shocked” at the news of He’s actions, adding that the researcher has been on unpaid leave since February. He said the university was unaware of his lab’s work

Harmonicare Medical Holdings Ltd., which owns the Shenzhen hospital that He said gave approval for the project, said in a filing Tuesday that it believed signatures on an application to the hospital’s medical ethics committee had been forged.

The controversial researcher rose to prominence in China by designing fast and cheap gene-sequencing machines through his start-up Direct Genomics, based in Shenzhen. Sina.com, an established Chinese news publication, reported in April that Direct Genomics received 218 million yuan ($31 million) in venture-capital funding that month.

Read: China Opens a ‘Pandora’s Box’ of Genetic Engineering

Last year, He was awarded a place in China’s prestigious The Thousand Talents program -- the government’s scheme to lure back top researchers from overseas with grants and research resources. Interviews and profiles published in recent years in local media reveal a driven, idealistic scientist who switched to biology only in his fourth year of university.

In one of the Youtube videos, He condemned the non-medical use of gene-editing tools, saying such uses should be outlawed as they are in the U.S. and other countries.

“Their parents don’t want a designer baby, just a child who won’t suffer from a disease which medicine now prevents,” He said. “Gene surgery is and should remain a technology for healing. Enhancing IQ or hair or eye color isn’t what a loving parent does. That should be banned.”

--With assistance from Robert Langreth, Stephanie Hoi-Nga Wong, K Oanh Ha, Daniela Wei and Rachel Chang.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Drew Armstrong at darmstrong17@bloomberg.net, Timothy AnnettMichael TigheBhuma Shrivastava

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.

With assistance from Editorial Board