Frozen Out of China, American Farmers Refuse to Sell Their Soy

Frozen Out of China, American Farmers Refuse to Sell Their Soy

(Bloomberg) -- Caught smack in the middle of the U.S.-China trade war, America’s soybean farmers are taking a huge gamble.

Rather than selling the crop right away as they pull it out of the ground -- as they do almost every harvest season to pay the bills -- they are instead stashing it in silos, containers, bins, bags, whatever they can get their hands on to keep it safe and dry.

The hope is that over the next few months, trade tensions will ease, and China, the top market for the oilseed, will start buying from American farmers again, lifting depressed prices in the process. A bushel of soybeans fetched just $8.87 on Friday. Eight months ago, before trade tensions led to tariffs, it was about $2 more.

The risks are great. While futures trading indicates higher prices next year, that could change depending on trade negotiations and rising supplies. Moreover, the crop could go bad on them. Soybeans are not corn. They don’t store nearly as well. If not kept super dry, they can take on moisture fast. Rot quickly follows, making them worthless -- and gross.

“It smells like road kill,” said Wayne Humphreys, a farmer in Iowa. “It has the consistency of mashed potato, slick and mushy.”

Still, Humphreys is going to put as much of his harvest in silos as he possibly can because he likes to time his sales to the market. “It gives you a certain amount of control,” he said.

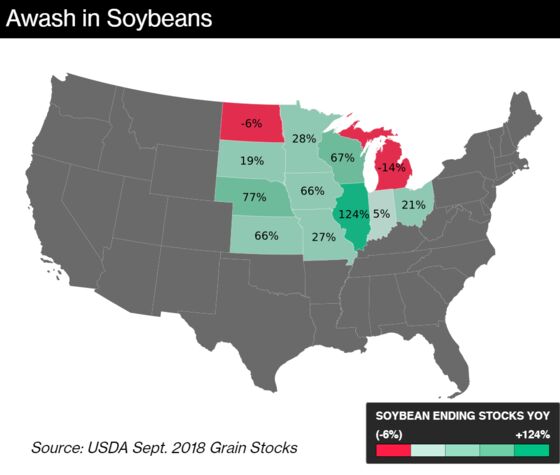

The scramble for storage comes just as soy production is reaching a record. American growers are trying to recover as overall farm income is projected to fall for the fourth time in five years. Chinese appetite for soybeans, used in everything from hog feed to cooking oil, had once been a bright spot. But with the onset of tariffs, the country’s imports of the oilseed from the U.S. have plunged, falling almost 90 percent in September from last year.

For some farmers, there is little choice but to keep their harvest. Millions of bushels have nowhere to go. Terminals in Portland, a key outlet in the Pacific Northwest to ship to China, are rarely offering bids. Supplies are backed up at terminals and elevators, even as cold, wet weather in North Dakota has left many acres unharvested. The country’s soybean inventories are expected to more than double to about 955 million bushels by the end of this crop year, according to the USDA.

Iowa grower Robb Ewoldt, who’s been farming since 1996, is storing most of his soy for the first time in about 15 years. His crop usually floats down the Mississippi River, about a half mile from his fields, on barges for export through the Gulf of Mexico to China and other countries. This year he’s stashing beans in his silos, making room for them by selling or storing his corn in commercial storage, to await higher prices.

“It’s probably more advantageous to store this year than any year in the past,” he said.

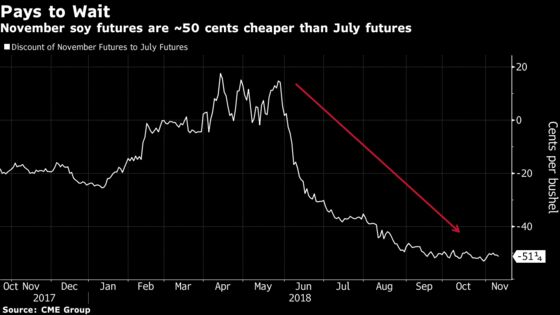

Soybean futures for delivery next July were about $9.27 as of Friday, indicating selling later may bring in more money. And traders are speculating that China-U.S. trade tensions may ease as the countries discuss a deal heading into the Group of 20 meeting in Argentina this month.

Space for all the extra soy is tight. That’s leading to some rarely taken measures, such as piling beans on the ground -- risking their exposure to bad weather. More farmers also are stuffing them into sausage-shaped bags that can stretch the length of a football field.

“I’ve heard farmers and commercial companies putting corn and soybeans into tool sheds and caves,” Soren Schroder, chief executive officer of Bunge Ltd., the world’s largest soybean processor, said in an interview last month.

The tariffs have particularly hit exports from North Dakota, where the expansion of oilseed acreage was a direct result of the growth of Chinese demand. The state plants the fourth-highest number of soybeans in the U.S. and about 70 percent go to Asia, largely because of its geographic accessibility to western ports.

Finding Space

North Dakota farmer Mike Clemens is so in need of space that he’s breaking out a dozen and a half bins built in the 1960s to store about 45,000 bushels of soybeans, which is half his farm’s production this year. He expects to fill up his five new silos with 300,000 bushels of corn.

Sarah Lovas, a grower in Hillsboro, North Dakota, has drawn several diagrams to map out storage for her entire crop. Her current plan is to fill up her 400,000 bushels of on-farm storage with 50,000 bushels of soybeans and the rest with corn. She’s renting grain bins for soybeans from a neighbor for the first time, to store about 68,000 bushels.

“I wish I had more bins,” Lovas said.

Farmers belonging to the James Valley Grain cooperative in southeastern North Dakota are hauling in so much that it will store at least 2 million bushels of crops in bags this year, twice as much as last year. The cooperative has 400,000 bushels of soybeans in one-time-use plastic bags, twice as much as a year ago, at its Berlin site.

Gingerich Farms in Lovington, Illinois, has used 300-foot plastic white bags for the last seven to eight years to store corn and soybeans. This year, the family operation has gotten as many as 10 calls from neighboring producers asking about how to use the bags, compared with one or two inquiries last year, said Darrel Gingerich, vice president of the farm.

“Corn is kind of a given,” he said. “They were calling us about bagging beans.”

Illinois, the largest U.S. soybean producer, may have the biggest storage shortfall, needing as much as 100 million bushels for storing crops, said Tim Brusnahan, an analyst with agriculture brokerage and consulting firm Brock Associates.

As of the start of this month, the Illinois Department of Agriculture had received requests for 11.6 million bushels of emergency storage capacity, such as bags, nearly triple the amount from a year earlier. Requests for temporary storage such as structures with waterproof covers increased 4 percent.

While Illinois’s crops are less dependent on China demand, today’s low prices make storing the soy a better choice, Gingerich said.

“The markets tell us to store it,” Gingerich said. “It’s tight, very tight.”

To contact the reporters on this story: Shruti Date Singh in Chicago at ssingh28@bloomberg.net;Isis Almeida in Chicago at ialmeida3@bloomberg.net;Mario Parker in Chicago at mparker22@bloomberg.net

To contact the editors responsible for this story: James Attwood at jattwood3@bloomberg.net, Kara Wetzel, Millie Munshi

©2018 Bloomberg L.P.