Macron Brought Jobs to Lens But Le Pen’s Taking the Votes

Macron Brought Jobs to Lens But Le Pen’s Taking the Votes

(Bloomberg) -- When Emmanuel Macron visited France’s former mining heartland in February, he came with what he called a moral obligation to show people the state would improve their lives.

The economic situation in Lens, the president told a gathering of local officials, had already gotten better with a sharp decrease in unemployment, less poverty, state investment in housing, and fewer people claiming the most basic level of welfare support. “For our citizens here who have sometimes had doubts, have sometimes been angry, and with good reason, I want us to restore the meaning of keeping your word,” Macron said.

But if Lens alone elected the French president, it wouldn’t be Macron.

On paper Macron should be popular in Lens, where unemployment stood at 10.2% at the end of last year, down from more than 14% when he took office. Yet from the town’s market stalls to its cafes and factories, people aren’t talking about his successes — their prime concern is the cost of living as prices rise, an issue his nationalist nemesis Marine Le Pen has focused on resolutely.

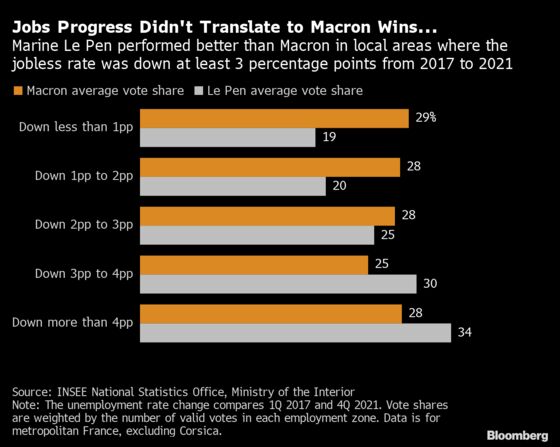

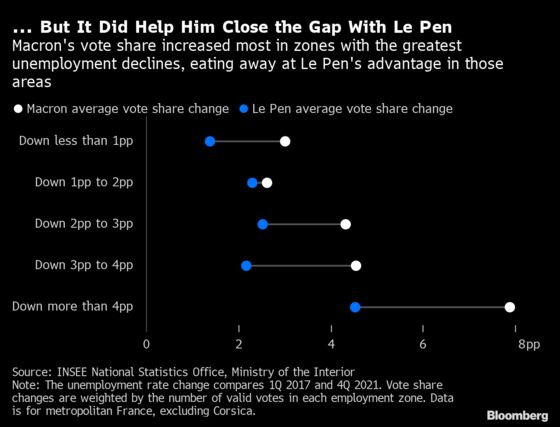

Le Pen won a majority in the runoff in Lens in 2017 and came out ahead of Macron here in the first round of this year’s presidential vote on Sunday. The town is a microcosm of industrial France, mirroring many parts of the country where he has struggled to loosen her grip. Although bringing new jobs to the French heartland has provided some political benefit — he did close the gap with Le Pen in regions with the greatest unemployment declines — it wasn’t enough to put him ahead in those areas.

“Even people benefiting from new jobs are affected by the problem of purchasing power,” said Remy Belval, the chief of public affairs at TT Plast, a maker of recycled plastic bags. “The value you get out of work in financial terms isn’t obvious. To work, you need a car, and gas, and childcare, that costs money.”

Hoping to preempt the risks as the election approached, Macron sent 100-euro handouts dubbed “inflation compensation” to 38 million people last year and has earmarked around 25 billion euros ($27 billion) for measures including a cap on gas and electricity prices. The government’s efforts have kept French prices from rising as fast as in most European countries, but Le Pen is betting it’s not enough to reassure people. She promises more radical steps such as slashing sales taxes on some basic goods as well as on fuel — a key issue for voters in rural areas.

Polls already show it will be a much closer runoff ballot on April 24 than last time, when Macron defeated Le Pen in the second round with a margin of more than 30 points.

Beyond France, Le Pen’s resilience is a cautionary tale for governments of advanced economies faced with forces seeking to sweep away established political orders and lead a retreat from the globalized economy.

Thomas Michaud, who works in a factory making plastic containers and bottles, says any benefits from job gains haven’t trickled down to people like him. “In Lens we don’t feel it.” Instead, Macron’s legacy is protecting the ultra-rich, he says, while Le Pen has stepped into a political space vacated when people lost faith in Socialism. “That doesn’t mean these people are racist, it’s because they’ve had enough and want to see something change.”

Macron headed straight to northern France on the first day of campaigning between the two rounds of the election, visiting three towns where Le Pen led on the first day of voting. He said that while his program is solid, he’s open to discussing it and even watering down his planned pension reform.

“People don’t believe in promises any more,” Macron said in Denain, 30 miles east of Lens. “People’s lives need to change concretely, more quickly.”

All-but flattened in WWI and heavily bombed in WWII, Lens’ heyday came with the revival of the coal industry during three decades of economic expansion in France known as the Trente Glorieuses.

The legacy of that period is physically inescapable in the slag heaps dominating the town’s horizons and the long rows of squat, redbrick houses built for miners and their families. The demise of mining left an equally palpable social and economic legacy as the cradle-to-grave care of an all-encompassing industry disappeared almost overnight.

The area today is a Unesco world heritage site, which the organization describes as bearing testimony to the “quest to create model workers’ cities.” The heaps are a tourist destination, used by local sports enthusiasts to test their abilities to walk, run or cycle up and down the steep inclines. “After the mines closed there has always been difficulty transitioning to a new époque,” said Sylvain Robert, mayor of Lens and president of the broader district that includes Lievin.

Lens’ beating heart is right at the center of town: the Bollaert-Delelis stadium, home-ground of football team Racing Club de Lens. Known by the nickname Blood and Gold, the team’s history is closely woven with that of the mines and to this day the supporters chant Les Corons, a song lamenting the coal mining heritage.

“The football club, it unites everyone. It’s the people, whether you are rich or not, white collar or not, everyone agrees,” said Muriel Beaurepaire, the landlady of the supporters’ bar, Chez Muriel. “Thankfully there’s that. It’s the only positive thing.”

Steel, automotive and textile factories took up some of the slack in the job market when the pits closed, but without a plan for the future, unemployment remained above the national average and those industries later declined. Efforts to structure training for new sectors and to prepare workers for a competitive labor market are only just bearing fruit 30 years later, according to Robert, the mayor.

On the campaign trail handing out leaflets calling for “five more years,” Macron’s industry minister and local resident Agnes Pannier-Runacher says the improvement in labor markets is directly attributable to reforms of the last five years to simplify administrative procedures and give firms more flexibility to hire and fire. Still, she admits change won’t be felt overnight and compares the people of Lens to workers in the U.S. rust belt who feel the pain of decades of factory closures and job cuts and distrust for globalization.

“People here need a bit of time to feel the difference,” Pannier-Runacher said. “When new businesses open up it’s no thanks to politicians, when they close it’s the fault of politicians.”

The company Liberty Durisotti, based in the neighboring municipality Salumines, has been on the front lines of mining community’s battle to find a new economic path.

Started in the 1950s by two brothers, the firm repaired buses that transported the wives of miners to and from textile factories north of Lens before specializing a decade later in customizing commercial vehicles produced by regional automakers. It has survived the highs and lows of the car industry that forced two rounds of painful job cuts in 2010 and 2013 before being bought by British group Liberty House in 2019.

Government support helped the company through lockdowns of the Covid pandemic, but it’s harder to start up than it was to hit pause, Chief Executive Officer Francois Loor says. This year is shaping up to be a tough one, as global supply difficulties mean large parts of the auto industry are in forced hibernation. His objective is to preserve the jobs of 200 employees on the site and start re-hiring when the storm passes.

“I am viscerally attached to the staff of this company and I’m not alone,” Loor said. “All the people of the north have notions of human and societal values that go well beyond grand speeches or business plans.”

National Rally lawmaker Emmanuel Blairy is campaigning for Le Pen in Lens, where he played as a child with friends in the industrial wasteland now home to an outpost of Paris’ Louvre museum. He says workers still don’t have security and struggle to make ends meet.

“Both my grandfathers were miners and told their sons never to follow them into the pits, but at least they didn’t have a problem with spending power,” Blairy said. “Now, the end of the month comes at the beginning of the month.”

On the almost deserted market in Lens, industry minister Pannier-Runacher talks about the measures with stallholders, reminding them of cuts to residency taxes and advising them to shop around when they fill up their cars to ensure they benefit from a rebate Macron introduced when oil prices surged recently.

On one butcher stand, a woman called Chantal who didn’t want to give her last name, says inflation is heating up too quickly, forcing her to raise prices. It all comes back to spending power.

“People are buying much less,” she said.

©2022 Bloomberg L.P.