(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Ford Motor Co. is rolling out a new ad campaign with the slogan “Built to be a better big.” If nothing else, it evokes the sense of a two-ton truck rolling right over the English language. It also fits with Ford’s direction: Earlier this week, the company announced it was boosting production of SUVs for the second time in two years. Plus, it’s been almost a year since Ford said it was effectively exiting cars, apart from a couple of brands, including the Mustang.

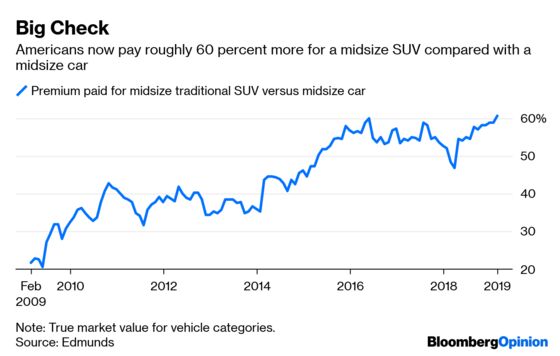

Ford isn’t alone in going all-in on “big.” Fiat Chrysler Automobiles NV went that way with its North American business in 2016. General Motors Co. announced in November it was ditching most of its car models as part of a sweeping restructuring. There’s a simple reason for this: Americans prefer bigger vehicles and are willing to pay more for them. On average, they paid about $51,000 for a large truck in February, according to data from Edmunds, and almost $42,400 for a midsize SUV, up 22 percent and 15 percent respectively over the past five years. Midsize sedans, meanwhile, fetched around $26,400, up just 3 percent. The premium for “big” is now the highest it’s been in at least a decade:

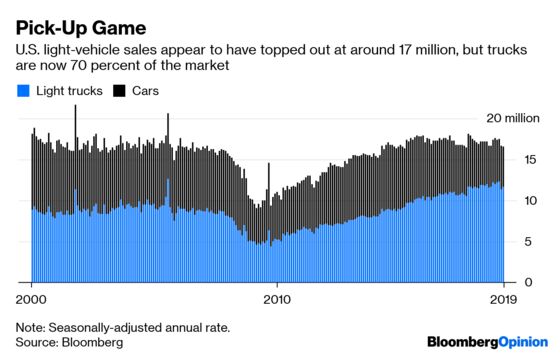

Even as overall vehicles sales in the U.S. seem to have topped out, the proportion of heavier models has kept on climbing — much to the manufacturers’ relief. While volume eked out a gain of just 0.5 percent in 2018, retail revenue climbed 1.6 percent, according to Kevin Tynan, Bloomberg Intelligence’s senior automobiles analyst.

That relatively simple math is why U.S. manufacturers “will keep pushing transaction prices higher until the consumer pushes back,” says Tynan.

There are some signs of fatigue on this front. Bloomberg Intelligence noted recently that discounting of new vehicles has picked up amid bloated inventories; supply of Ford’s F-Series trucks, for example, has averaged 104 days so far in 2019, versus an ideal level of around 55-65 days.

The average interest rate on new car loans increased from about 5.3 percent at the end of 2017 to 6.7 percent at the end of 2018, according to data from the Federal Reserve, and there are uncomfortable rumblings in the auto-loans business, with 30-day delinquencies hitting their highest level since 2012, according to data from Capital One. Subprime auto loans, especially, are a cause for concern, although that may have something to do with being associated with a certain word beginning with “s.”

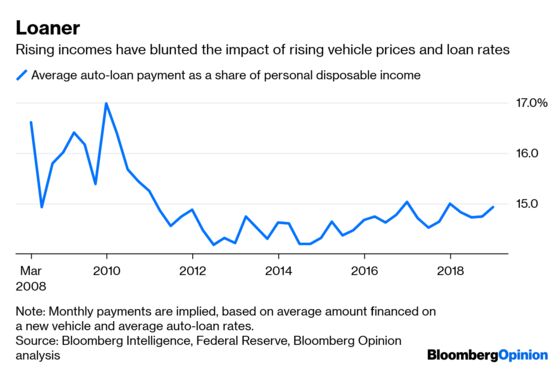

Rising price multiplied by rising rates equals higher monthly loan payments; up roughly an extra $24 to almost $600 on average in the U.S. since the end of 2017, by my calculation (Experian Plc’s tracker puts it closer to $550). But low unemployment and rising wages have blunted the impact thus far, keeping those payments at around 15 percent of per-capita disposable income:

Rising wages, along with better fuel efficiency, have also made the more-frequent visits to the gas station that SUVs and trucks necessitate more palatable (see this).

The retreat to the fortress of big makes sense in terms of squeezing as much out of the current business cycle as possible. But with that strength comes a certain fragility.

The U.S. automakers have largely ceded the car market to foreign firms such as Toyota Motor Corp. and Honda Motor Co. Ltd. at this point. If there is a recession or a jump in gasoline prices, then premium gas-guzzlers will look less tempting, and customers will have to look elsewhere if “smaller” is suddenly in vogue again (as happened in the last crash). As an aside, the popularity of bigger vehicles raises the political risk associated with higher pump prices; something that clearly irks President Donald Trump (though apparently not to the point where he recognizes how it might intersect with his push to loosen fuel-economy standards).

All incumbent manufacturers are juggling the challenge of making profits on traditional vehicles while investing in various electrification and autonomous-driving technologies. Ford, playing catch-up on both fronts, also announced this week a $900 million investment to build electric and self-driving vehicles at its Flat Rock plant south of Detroit. It is, like its peers, effectively betting that today’s trucks can fund both dividends to appease shareholders and spending on new products to keep the company relevant in tomorrow’s transportation market.

This may work — if the consumer remains resilient and macro forces encompassing everything from the Fed to OPEC play ball. As ifs go, that’s a big one.

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Mark Gongloff at mgongloff1@bloomberg.net

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal's Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times' Lex column. He was also an investment banker.

©2019 Bloomberg L.P.